‘Professor Fungus’ Han Wösten wins research prize

‘25 years from now, hardware stores will sell a lot of mould’

It started ten years ago as an artistic side project. Wösten wondered if fungi could be used to develop textiles and other materials. At the time, the professor of Microbiology spent much of his time researching how fungi form mushrooms. He even patented genetically modified mushrooms, but they did not sell well. "No one wanted to eat them, so we couldn't sell them to the industry."

He then met the designer Maurizio Montalti, with whom he developed materials from fungi in projects that often involved other designers. It was a great success.

In 2016, the Dutch textile designer Aniela Hoitink made headlines with her fungus dress, which was the centrepiece of an exhibition at the Utrecht University Museum, opened by then-Minister of Education Jet Bussemaker. Since then, the development of fungus products has become Wösten's main line of research, and the technology has made enormous strides.

"The dress was made with individually cultivated cultures, which stuck together naturally during drying," Wösten explains in his office in the Kruyt Building. He then opens a box and takes an old piece of fabric made from the same material as the dress. The piece consists of several Petri dish-sized circles and appears brittle and fragile.

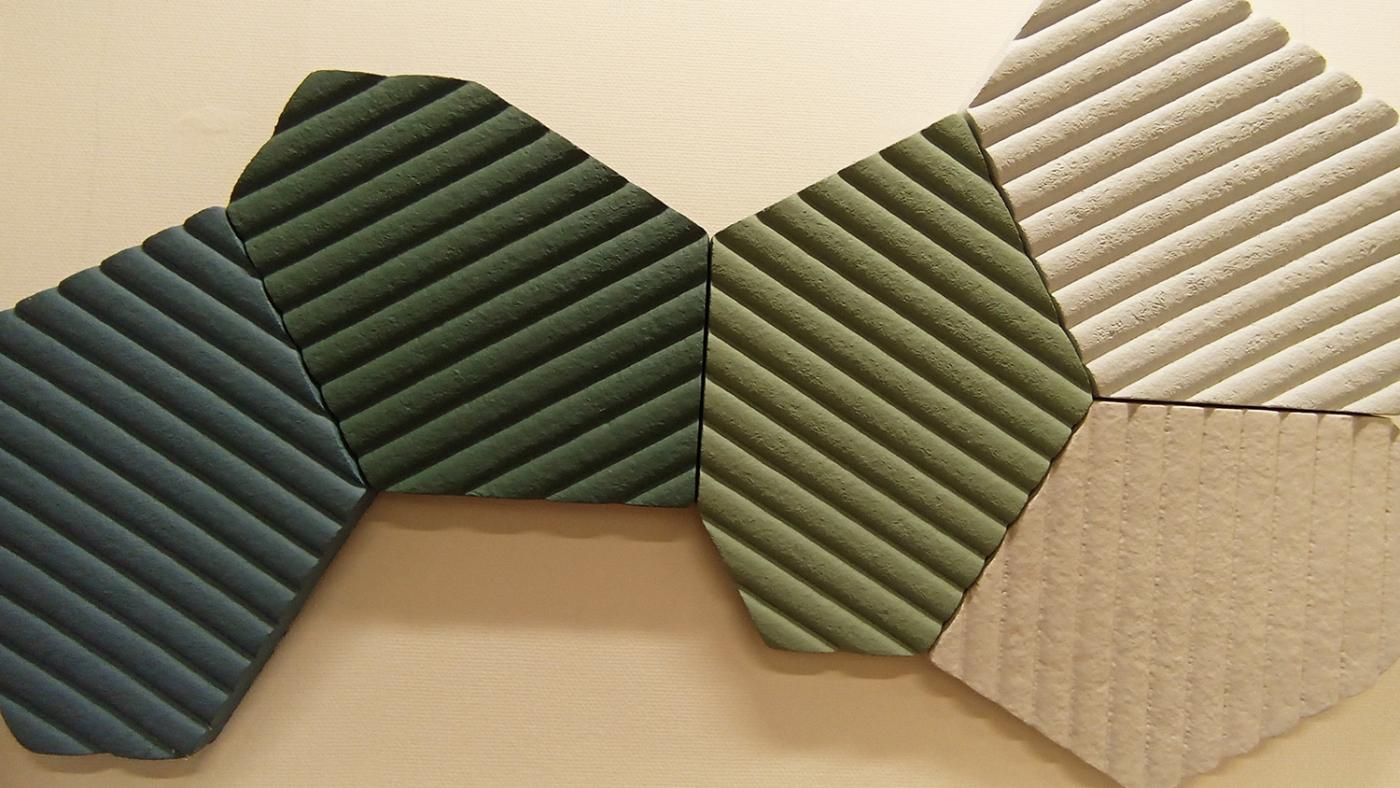

He also places several newer products on the table, including a soft brown material and a leather-like black fabric with an embossed pattern. "The black fabric was developed as part of an EU project in which Volkswagen also participated, and is intended to replace the leather interior upholstery in electric cars in the future."

Some mould products developed by the industry are already available for purchase. They range from sound-absorbing panels to flooring systems and even coffins and urns. Wösten received the Huibregtsen Prize on 16 October for his work on developing sustainable products from fungal threads. This prize highlights the work of scientists conducting innovative research with significant social value. Wösten considers it a great honour, but believes this field has only just begun.

No incineration or pesticides

Fungi form an underground network of threads, also known as mycelium. These networks can be used to produce materials with different properties. The first step is to select the food source – preferably a local waste product such as straw or sawdust – and the appropriate fungi capable of digesting it.

The waste is then placed in a suitable mould or space. "The fungus grows through the material, slowly eating a small part of the straw or sawdust. The fungal threads, often only a hundredth of a millimetre thick, then bind the remaining particles together," he explains.

A composition of mycelium and waste is created after one to two weeks. Straw contains many hollow spaces, making it suitable as an insulation material and for making acoustic panels. "But it is also possible to let it continue to grow. In that case, we end up with pure fungal material, which is what most leather alternatives are made of."

Wösten focuses primarily on local waste streams when developing his mould products. For example, he used waste from the local date and wine industries in a project with an Israeli university (which has already been completed). "We don't want to transport waste by boat," he says. By using waste as a raw material, one can prevent it from being incinerated and thereby reduce the release of CO2 into the air.

Fungal products also have the advantage of being environmentally friendly. "A white cotton T-shirt needs 2,400 litres of water to be produced, but the fungal dress only needs 12 litres. In addition, you can grow it under controlled conditions, so you don't need pesticides or herbicides." At the end of their life cycle, the products can be thrown on the compost heap, where they easily decompose.

Self-growing buildings and meat substitutes

When asked where we will be in 25 years' time, Wösten says that fungal products will be commonplace. "If all goes well, we will all be growing our own clothes and going to hardware stores where nothing is made of iron, plastic or wood anymore. Ten years ago, I wouldn't have dared to say such things, but now that I've seen what has happened in the last decade, I feel confident enough to make bold statements."

Wösten shows a piece of compressed sheet material that smells slightly of straw. "When people know that something is made from fungus, they immediately start sniffing it. Perhaps because they associate fungi with decay and toxic substances." However, that association does not seem to stand in the way of the material's success, as it is already available online as a floor covering.

The first products are already available for purchase, and he expects the number of shops carrying them to grow. Currently, fungi can be used to produce materials with properties similar to those of rubber, wood, and plastic. Imitating metals such as iron may be more difficult. "To do this, the material needs to be very dense and sturdy. We have considered allowing the mycelium to grow in layers on top of each other and then pressing it."

In addition to developing building materials, Wösten is collaborating with a Danish university to investigate the possibility of growing buildings in the same place where they are to be constructed.

"Suppose the Kruyt Building at Utrecht Science Park is stripped of everything, leaving only the concrete structure. We could then insert frames between them and grow fungi in them, so that the building grows, as it were, on the construction site." There is one caveat: the material breaks down when it gets damp, so it is necessary to coat the walls properly.

According to Wösten, fungi could also change our diet 25 years from now. He is currently working on developing a pea-based product as part of a Danish consortium. "Peas form a mushy mass and are not very easy to digest, which causes some people to become flatulent. Fungi can give that mush a structure similar to meat and also break down the hard-to-digest substances."

The biggest challenge of this project is that fungi also eat proteins, which are precisely what is needed in a high-quality meat substitute.

Intelligent fungi

Developing a well-functioning fungal product is step one. Scaling up production and selling it profitably is step two. Wösten explains that the tactic here is to focus on more expensive products and the luxury industry first.

"A good cast floor can easily cost more than a hundred pounds per square metre. Fungal materials can compete with that. Once that is going well, it will be possible to scale up, and the industry can start looking into products in the mid-range segment. Ultimately, cheaper products such as cling film or insulation materials such as glass wool could also be replaced."

Considering all the research he does into the application of fungi, does the professor still have time for curiosity-driven research? "To develop a product, you need to know how fungi grow, how they react to their environment and what the chemical post-processing should look like. That requires hardcore fundamental science. For example, we conduct microbiological research into the cell wall of fungi: how is it structured and why is it so strong?”

One of his favourite lines of research has been ongoing since 2001 and concerns the distribution of functions in the mycelium. "People often blindly assume that every fungal thread does the same thing, but that is not the case. Mycelium networks have different zones with different functions, such as protein production, food intake and digestion, and light or even sound registration. That's incredibly intriguing."

The different zones could be comparable to organs in animals. The professor wishes to gain a better understanding of this division of labour before he retires. "If you look at where fungi branched off in evolution, it is the branch from which the animal kingdom also originated. So they are more closely related to animals than to plants or bacteria, and possibly a lot more intelligent than people think."

Comments

We appreciate relevant and respectful responses. Responding to DUB can be done by logging into the site. You can do so by creating a DUB account or by using your Solis ID. Comments that do not comply with our game rules will be deleted. Please read our response policy before responding.