Part 1

How to memorise all the study materials you need for that exam?

Yes, you read it right. The answer is Ronald McDonald riding on a fire-breathing ostrich. Any further questions?

Oh, fine. Maybe we should take a step back.

How on Earth should a student be able to remember all of the important information from a course? An excellent question.

When we are trying to etch new information into our memory, we usually repeat it either verbally or visually (i.e. rereading it). This is how we try to move the information from our short-term memory into our long-term memory. In this first part of Mnemonics, we will focus on coding and storing the information that we wish to learn, by using the magi… I mean the science of mnemonics! Also known as memory techniques.

Furnishing your attic

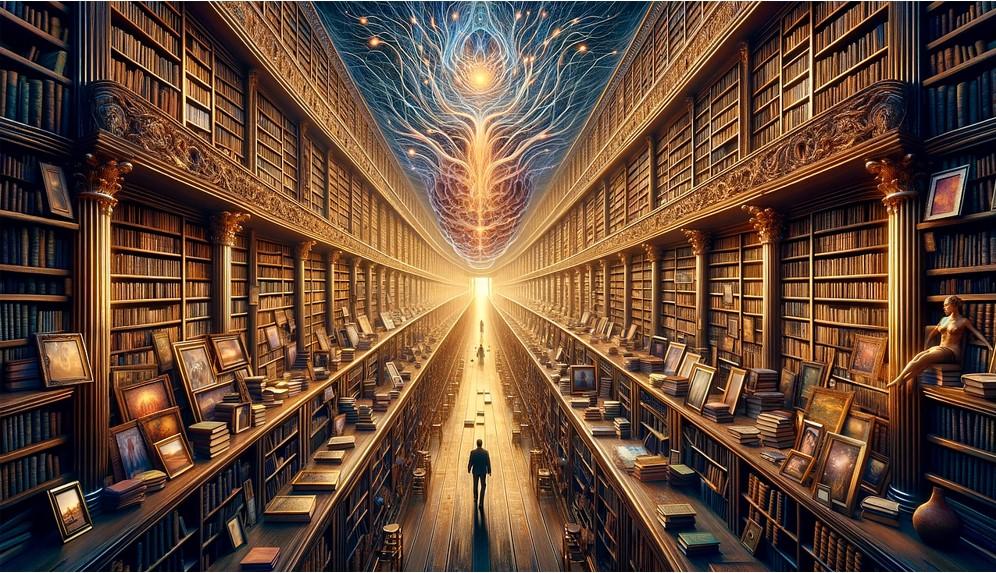

Imagine that our memory is an attic. What most people do with new information is throw it into this brain attic without any second thought, like throwing old gadgets in a pile. The problem is that successfully fishing out what we need from that disorganised heap - e.g. the answer to an exam question - is rather difficult. To turn that messy pile of memories into a neatly organised mind attic, with labels and categories, we need associations.

Before humans began to think about data in numbers and graphs, our ancestors memorised places and events to survive. This is why our minds are tuned to do just that and it is what memory artists and champions do to this day. To effectively memorise a piece of information, you need to associate a character or an object with it and turn it into a scene. Accept the first thing that comes to your mind as that is probably your strongest association. Take your mind to solidify the image in your mind and work on the details. Think about how it sounds or how it smells to make the association stronger. When memorising numbers, it is better to have a prepared coding system that is based on the associations that first come to mind when seeing / thinking of a number. Do this for every number from zero to nine. The number one might be a pillar. Number six a snake, the seven a scythe, and so on.

Practice, practice, practice

For example, when trying to memorise that in 1676, Mr. Leeuwenhoek first discovered the existence of bacteria, you could store that information as a scene of a sneezing lion, lying in a corner. There is a beautifully carved marble pillar with a huge green snake wrapped around it on the lion’s left side, and while lying around the lion is trying to dodge a scythe wielded by a second, brown snake on the lion’s right side. What is really going on here? Well, ”sneezing” means being sick, which can be because of a bacterial infection. “A lion in the corner” translates to “een leeuw in de hoek”, which gives us Mr. Leeuwenhoek. The marble pillar is the one, the green snake is a six, the scythe is the seven, and the last snake is also a six, which gives us the year 1676. This is only one of many possible associations but be sure to use your own fascinating and weird connections. The same strategy of narrative building can be used when memorising a long equation or the many steps of a specific process.

The image needs to be vivid. You need to be able to see it, hear it, smell it and even feel it. It needs to be the first thing that comes to mind. Is it weird, random, ludicrous or even disgusting? Excellent! If the image has an emotional valency, or if it is somewhat confusing, then it will be that much easier for the brain to remember it. Like Ronald McDonald riding on a fire-breathing ostrich!

This tactic of narrative-building works best for visual thinkers, but not exclusively. Similar associations could also be written into a poem, or a funny phrase, or even a song. The point is to be creative and to experiment with what works best for you.

Read Part 2 to learn how to code large amounts of information easily, and how to stop yourself from forgetting it.