A welcome escape

Let’s get dirty

Begrudgingly scrolling through social media on my ten-minute Pomodoro break from writing my thesis, I haven’t quite found the post that will scratch my dopamine itch just yet. Ten minutes becomes forty. Another dog whose best friend is a duck isn’t going to cut it today, I need something else. Ah, a right-wing couple stoking panic about infertility and decreased birth rates. A confusing take when conservatives are known to be anxious about "overpopulation" — hot tip, overpopulation is a racist myth. In the few split seconds, it takes for my subconscious to consider the pros and cons of this particular doom scroll my thumb has already inched upwards and revealed the next post. Ahhh. Cleaning.

Before I got here, the final six weeks of my thesis, I imagined the writing process to involve late nights becoming early mornings, furiously writing amongst towers of laundry and teetering skyscrapers of dishes. However, in reality, I have spent hours bleaching, scrubbing and vacuuming my way through each version of my proposal. The old hodgepodge mix of recycling in our entry hall is now a dust-free, demarcated and labelled zone. Ditto for our Tupperware, each base now satisfyingly coupled with its lid. Those who couldn’t find their pairs were surrendered to become pot plants or trash. Amongst the imposter syndrome and procrastination of thesis-writing (which are actually the same thing), compelling orderly systems of efficiency on my housemates has been a welcome escape.

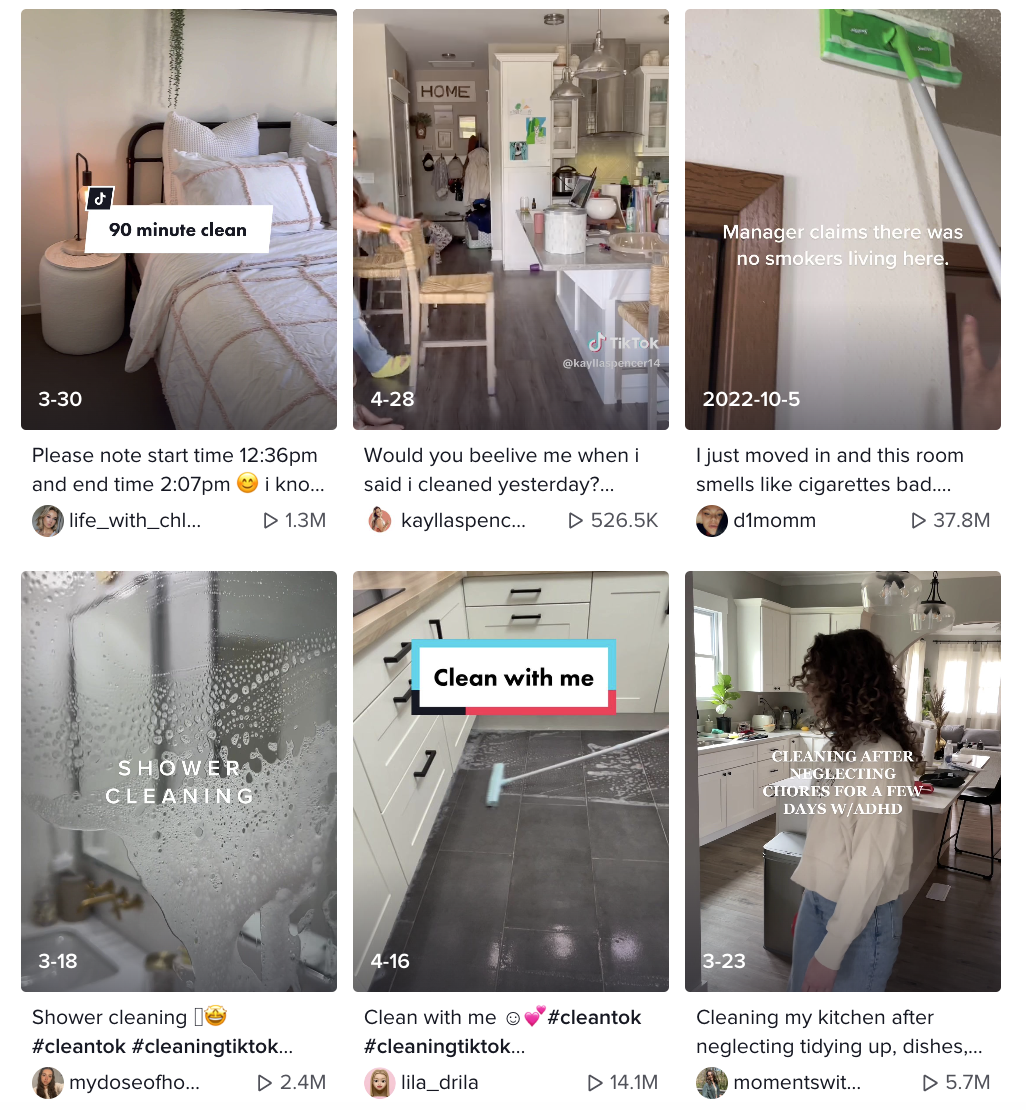

Like the millions of other women watching "cleanfluencers" on social media, I find it incredibly soothing to watch. The organisation, purposefulness and repetitive motions are like ASMR to my eyes. But just like the algorithm that is designed to always leave you wanting more, once something is clean it’s both a relief and a disappointment. The task is done. For a while. Until it must be done again.

Sociologists Dr Emma Casey and Professor Jo Littler attribute the rise of the "cleanfluencer" to freshly stoked anxieties about bacteria and viruses post-pandemic, as well as social media being the latest tool to enforce gender roles, a “new [way] of ensuring women’s willingness to participate in unpaid domestic labour”. The women creating cleaning content are usually white women and their followers are overwhelmingly women too. This is especially concerning when women around the globe, especially those who are poor and have racialised bodies, still do the majority of the world’s domestic labour, either for very little or for free. I like Ursula Maki’s revival of the no-more-lost-to-obscurity "housewifisation" to talk about this trend. A word that explains everything all at once. As Maki remarked at a recent Gender Studies conference in Berlin, "housewifisation" upholds and naturalises patriarchal ideas which place the burden of housework and home-making squarely on women.

I’m caught between my love of #cleantok’s soothing videos of deep-cleaning shower heads and the blatant hyper feminisation of cleaning. Femininity, at least the traditional kind, has always been something I’ve picked up, examined, maybe even tried on, and discarded. Not unlike an ugly sweater at a flea market. It scratches and just doesn’t fit. But there’s a thesis to finish, and I’m already eyeing the jar of make-up brushes which are begging to be deep-cleaned.