Corona bigwig Berend Jan Bosch: “Antibodies have the potential of fighting infectious diseases”

Globally, Berend Jan Bosch (45) of Utrecht University is the most-cited corona virologist. Two years ago, he and his colleagues created 51 antibodies against the previous SARS virus. Now it turns out that one of them also blocks the new coronavirus. During a press conference on Thursday, May 14, he explained his discovery to the international media.

Berend Jan Bosch, you’ve been studying coronaviruses for more than twenty years, and suddenly, your specialty is global news. What does that do to you?

“It’s overwhelming. From the medical perspective, there’d never been a lot of attention to coronaviruses, because in people, they only cause common colds. Amongst animals, however, they’re notorious pathogens, which is why the faculty of Veterinary Medicine has been studying them for forty years now. The attention for this family of viruses increased after the SARS-coronavirus outbreak (2003) and the outbreak of the MERS-coronavirus (2012), which both caused severe respiratory infections in humans. For the three-yearly international convention for corona virologists – which, ironically, has now been cancelled because of corona – we hoped to have two hundred attendants. Now, there’s a huge amount of interest from the media, companies, and scientists, including those that aren’t virologists, who all come to us for knowledge. That feels surreal.”

That’s because ‘your’ virus caused a pandemic…

“Yes. As a virologist, I’m fascinated by the biology of these viruses, but at the same time, the effects they cause make me very sad. The impact the current coronavirus has globally on humans and societies, is unprecedented. We knew there was a chance that viruses could be transmitted from animals to humans and cause a pandemic, but I’m still surprised by the enormous impact this current outbreak has. That’s the tricky thing with infectious diseases: you’re always playing catch up with the facts.”

But now you’ve found an antibody that blocks the virus. Does that mean the end of the corona crisis is near?

“That would be great, but there are still a lot of steps that need to be taken. Moreover, I hope that solutions will be found from multiple perspectives. We’ve now taken a first step in the right direction. I won’t see this as a breakthrough until the antibody can be successfully used as medication for humans.

“The antibody had been lying in the freezer at the faculty of Veterinary Medicine for two years. It came from previous research that I’d started in collaboration with Frank Grosveld from the Erasmus MC, on the development of human antibodies against various coronaviruses. The antibody blocks the infection of the cells, and call also help with recovery. Now, the phase of testing on animals has started. The plan is to work together with a pharmaceutical organisation to use this antibody as medication for the most vulnerable people, like the elderly.

“We’re seeing that the level of antibodies in patients’ blood is remarkably low. By administering the right antibodies from the lab, you give your patient direct defence against the virus. The timelines for such therapies are usually shorter than for vaccines, and if everything goes really smoothly, we’ll be able to treat the first patients with the antibody in six months.”

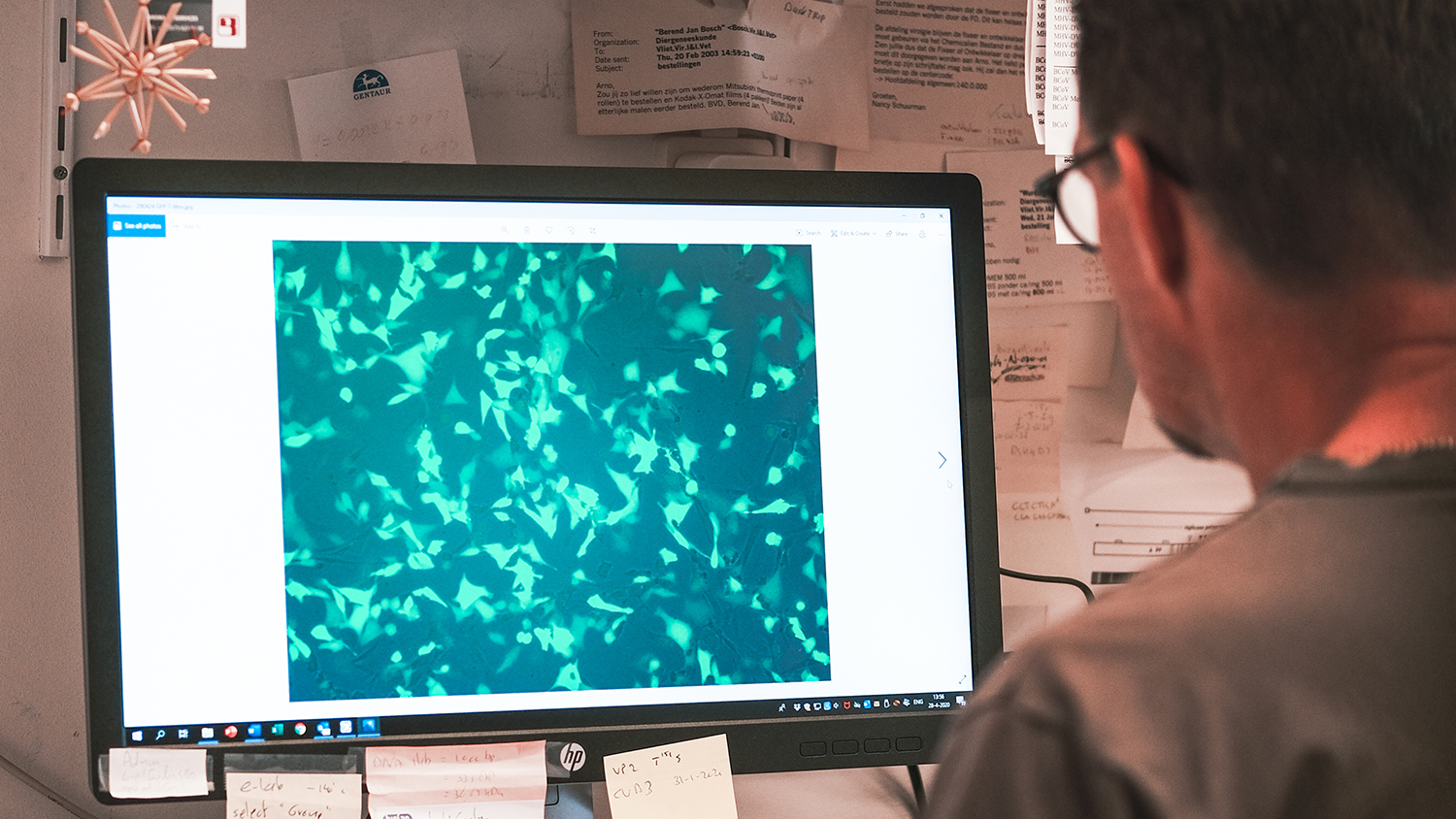

Researchers at Utrecht University are studying the new coronavirus, COVID-19. They’re working on the development of vaccines, antibodies, and diagnostic tests. Photos: Bas Niemans, UU.

Six months, that’s great news! And what’s the big difference between antibody treatment and a vaccine?

“With a vaccine, a weakened or dead piece of the virus is presented to one’s immune system. The body will then start to create defences and antibodies, so it will be able to respond quickly once that person’s infected with the actual virus. Using the genetic code of a neutralising antibody, the antibody can also be created outside of the body. We’re doing that in transgenic mice. You can directly administer antibodies to patients. In the fight against Ebola, it became clear that antibody treatment is an effective treatment.

“I’m convinced that antibodies have a lot of potential in the treatment of infectious diseases. Now, it’s mostly unchartered territory. Antibodies are one of the most important defence molecules the body creates by itself in its fight against infectious diseases.

“It’s possible these antibodies, or cocktails of antibodies, will be able to partially replace vaccines in the future. Especially among certain groups like the elderly, for whom vaccines are at times barely effective. At this time, antibody treatment is still very expensive, but steps are being taken in that, too.

“Recently, we were offered funding for a number of national and international research projects that enables us to expand this study, and within the Utrecht Molecular Immunology HUB, we’re translating this knowledge to new vaccine concepts. In European projects, we’re also looking into ways of shortening the timelines for product development of antibodies and vaccines. Currently, it still takes a long time before a vaccine or antibody makes it to the clinics; we would like to see that time period shortened. All of this is for the goal of being better prepared, and to be able to respond more quickly, to new viral diseases.”

Has been corona virologist since 1998

Is associate professor at the faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Utrecht University

Studied Plant Breeding and Crop Protection (specialisation: Virology) at Wageningen University & Research, from 1993 to 1998

Obtained his PhD at Utrecht University in 2004, for his research on the protein in coronaviruses

Is married, and has two children

Wants to thank colleagues and scientists all over the world for their collective efforts in the fight against the coronavirus

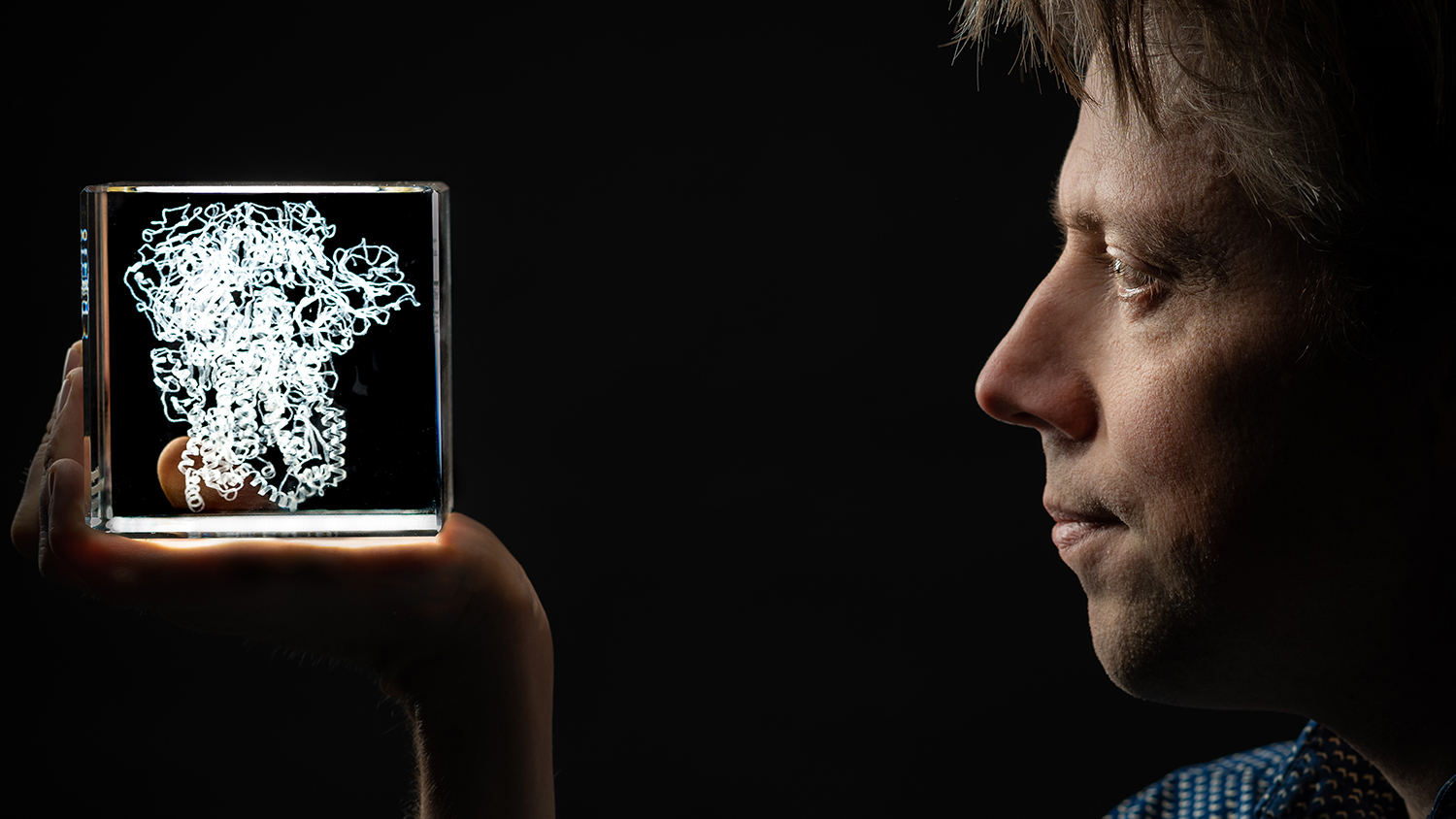

Berend Jan Bosch looks at a ‘spike complex’, the element that a virus uses to enter a host cell. Photo: Bas Niemans.

What about collaboration? Do you share the knowledge with the rest of the world?

“It’s not done to keep knowledge to yourself right now. I think many scientists feel the urgency of sharing knowledge, even if it isn’t always in your own best interest. From the start, that’s been the approach: in times like these, you can’t just be working for yourself. The extraordinary thing about this corona crisis is, in fact, that enormous willingness to collaborate. Not just in Utrecht, but on an international level as well. And there’s a great need for that – you can achieve a lot more by working together.

“Every day, we send packages to labs across the world to provide them with reagents – antidotes and antigens (virus molecules). We can produce these antigens in the lab at large scale, and they’re used in blood tests all over the world to see whether someone’s had the infection.”

But how do you make sure another scientist won’t take your idea to the pharmaceutical company to make millions off it?

“We’re providing this under the Material Transfer Agreement. That’s a contract that enables the researcher to use the materials for research purposes, but he can’t exploit them for commercial purposes.”

You’ve been in the media a lot lately, in news programme Nieuwsuur, for instance. What happens if you’re claiming and promising things that turn out not to be true?

“That risk exists. But to make that risk stop you from going public… I think you should inform the public, that’s a duty you have as a researcher. I don’t personally like being in the spotlight; in fact, I dread it.”

Finally: next to your research, and doing interviews, is there any time left for your family?

“Not a lot, but they understand. I get a lot of support from my wife. My 11-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter have spent the past few months at home, while my wife worked from home as a secondary school teacher. They handled the situation perfectly. Lately, I’ve been working sixteen hours a day, seven days a week. In the future, I hope to lead a normal family life again.”

When do you think that will be?

He laughs. “You tell me.”

This is an interview in the series of ‘UU corona bigwigs’. Previous interviews in this series were held with doctor-microbiologist Marc Bonten and epidemiologist Patricia Bruijning.