Course evaluation format uses Dixit cards, acrylic drawings and sound recordings

Creative evaluations allow for richer, more nuanced feedback

Course evaluations have their pitfalls: students often don't answer all questions and anonymity sometimes results in hurtful or inappropriate remarkers. In addition, students are usually kept in the dark about how exactly lecturers will use the input. Questions abound: Are these evaluations useful? Do they meet their purpose? Do they do more harm than good? Recently, student Ize van Gils published a blog post on DUB (available in Dutch only, Ed.) calling for mid-term evaluations that would support the evaluations done at the end of the course. DUB has also published an article about an experimental project surrounding an alternative evaluation format involving colours, association cards, and dialogues. Below, the team behind the project tells us how that went for students, lecturers and the programme involved.

The design

The idea for this project was born out of our desire to collect more varied information from students regarding their experiences with the course. We already used several creative working methods in the Face-to-Face Communication course of the Communication & Information Sciences programme, so we wanted to extend that to course evaluations. We suspected that an associative, open, dialogic form of evaluation would yield richer information than the format offered by the digital tool Caracal, which is rigid and limits reflections. For example, students can't judge their own roles in the course.

That's why we evaluated the course during the last working group meeting, using brush pens, acrylic markers, association cards and dialogue. We've submitted the design for this experiment to the faculty's Ethics Committee (FETC). One of FETC's demands is that we guarantee the anonymity of the respondents and that course evaluations do not influence grading. FETC approved our project, which also received funding in the form of a Scholarship for Teaching and Learning.

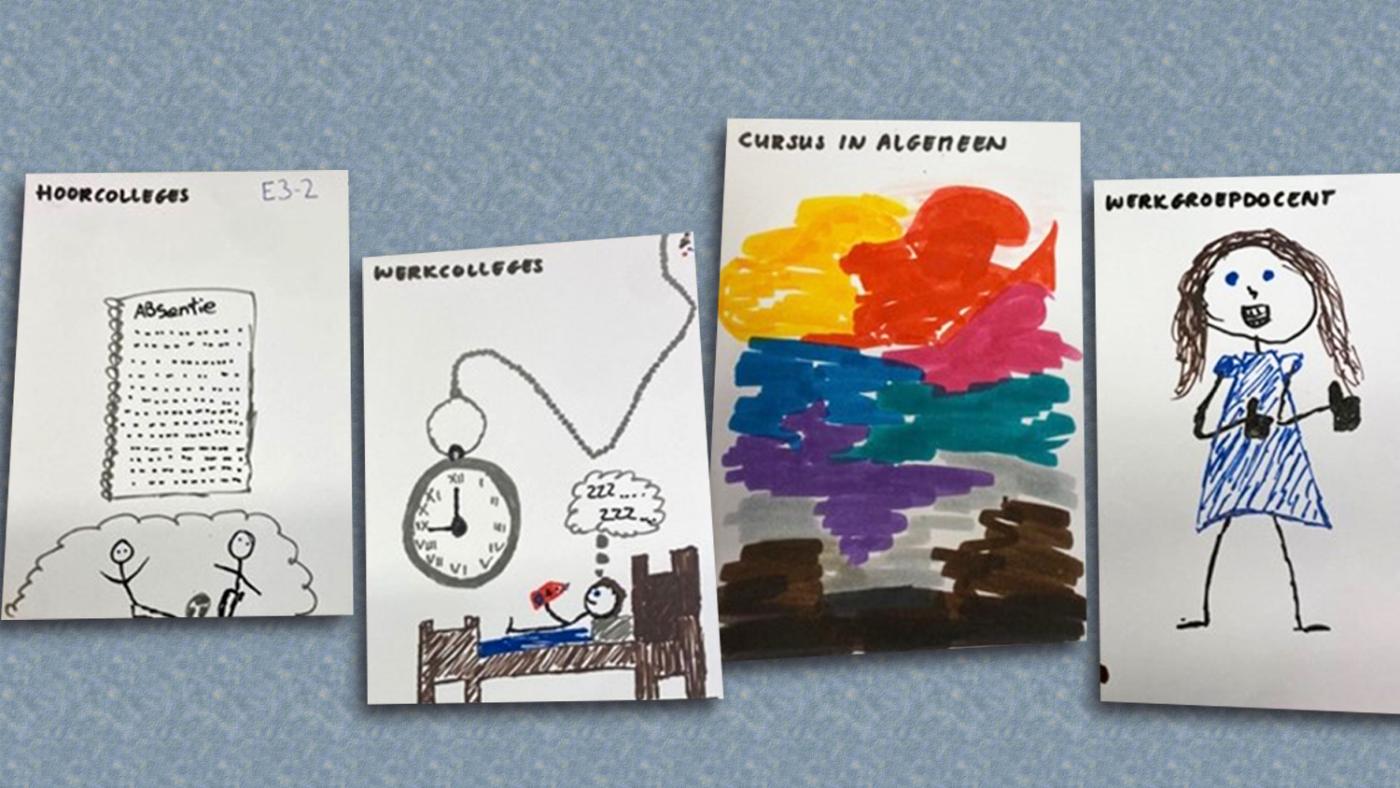

During the final working group meeting, each teacher introduced the experiment to their respective group. Students were then given 40 minutes to evaluate four components: lectures, tutorials, the working group teacher, and the course in general. They could use acrylic markers or brush pens to draw their free associations with those components. Another option was to use Dixit association cards for the components.

After a short break, the students went out into the hallway in pairs to tell each other about their drawings or chosen cards. That conversation lasted five to ten minutes and was recorded with their phones. Once they returned to the classroom, they uploaded their conversation and a photo of their drawings/cards to a SurfDrive folder. This folder was only accessible to the student assistant in this project, for anonymity reasons.

To prevent student evaluations from influencing the grading process, the student assistant only gave teachers access to the folder after all grades had been entered on Osiris. In the meantime, she organised the data and transcribed the conversations using the automatic transcription service Amberscript. About a month after the end of the course, the workgroup teachers could see the submitted pictures of the drawings and maps and then discuss these with teachers and student assistants in a meeting led by educational advisor Esther van Dijk. The questions discussed in that meeting include: What kind of information did this evaluation format yield? How does this information differ from Caracal results? Is the information valuable? What were the workable ingredients from this way of evaluating? The aim was to gain insight into how effective this evaluation format was for students and teachers, how much they appreciated it, and how the data collected relates to Caracal results.

Evaluation materials included tissues, brush pens, acrylic markers and the Dixit game.

What kind of information did it yield?

The experiment yielded valuable drawings and Dixit card choices around the four subjects (lecture, tutorial, teacher, and the course as a whole). Students explained their drawings and associations in the conversations they had with each other. This form of evaluation yielded more personal reflections, but we've also noticed that not all students are open to this method. The drawings and quotes below show the advantages and disadvantages of this evaluation format.

The advantages…

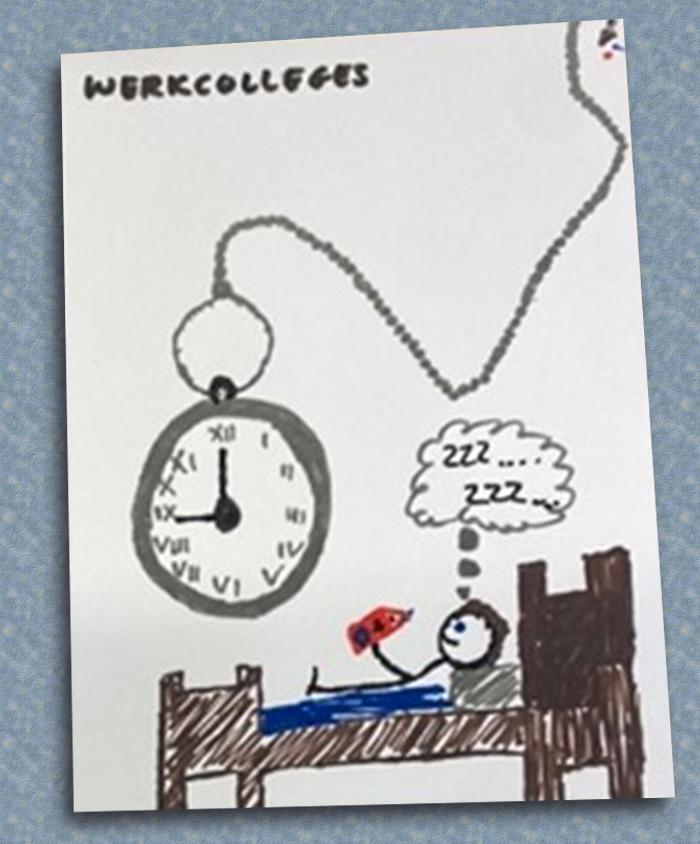

Firstly, the associative and open nature of this alternative method means that students are much less guided by predetermined questions. This allowed them to say what was important to them, which provided teachers with richer information compared to what they get through Caracal. This drawing is a good example:

Explanation of the drawing:

“During the tutorials, I just started doodling and then I drew myself reading a book in bed, just wanting to sleep because the tutorials always started very early for me. Well, I was often late too, but I do think they are interesting. I mean, I am still reading a book in bed.” [Transcription]

This explanation offers more nuance (he is in bed, but still reading a book, so not totally unmotivated) than a typical Caracal evaluation, which would be "Tutorials started too early".

A second advantage is the possibility of a dialogue. Due to the face-to-face interaction between students during the recordings, certain answers are given more nuance (see quote above). Students complement each other and ask each other clarifying questions, such as in the interaction below:

Interaction between students 1 and 2 in conversation:

Student 1: “(…) Even though I thought the material was boring, I didn’t mind going to the tutorials, because it was always filled nicely, so to speak, hence the cheerful colours.”

Student 2: “Yeah, I agree with that. I also drew flowers (…) because she was always considerate(…), which I appreciated. Prob... Like, she created a good…”

Student 1: “A warm atmosphere.”

[Transcription]

Thirdly, the conversations offer a glimpse into the students' experiences. One student indicated that he preferred football to the lecture:

Student's explanation from a conversation:

"I got an absence note because I was often not in class. My priorities were elsewhere at the time." [Transcription]

In the recordings, Students first share their experiences before assessing the course, unlike Caracal evaluations, where they are asked to give an assessment and their experiences remain invisible. Caracal gives students fewer opportunities to enlighten their assessment. Here is an example:

Student explanation taken from a conversation:

“I gave the lectures four stars because I found them pleasant. They were pleasant lessons. The speech was very clear and the PowerPoint presentations were very useful. Thanks to them, I knew exactly what I had to learn, what mattered. The only disadvantage was that it ended at seven o’clock in the evening.”

[Transcription]

A fourth advantage is that this evaluation format makes it easier for teachers to gain insight into their teaching methods and how these methods are experienced by students. Instead of just receiving a grade for didactic skills, teachers now get more targeted information. The new method can therefore be highly suitable for teacher professionalisation. In the focus group that followed the experiment, a teacher said:

Teacher participating in the focus group:

“Yes, yes, the best compliment I got from a student (…) is a term that I have come across several times on Caracal last year, but they never really explained it. And now they have. The term is 'safety'. I think that is a very nice compliment because that is exactly what I would like to have myself. That means being in a tutorial and having the freedom to say things, even if they might be wrong.”

[Transcription]

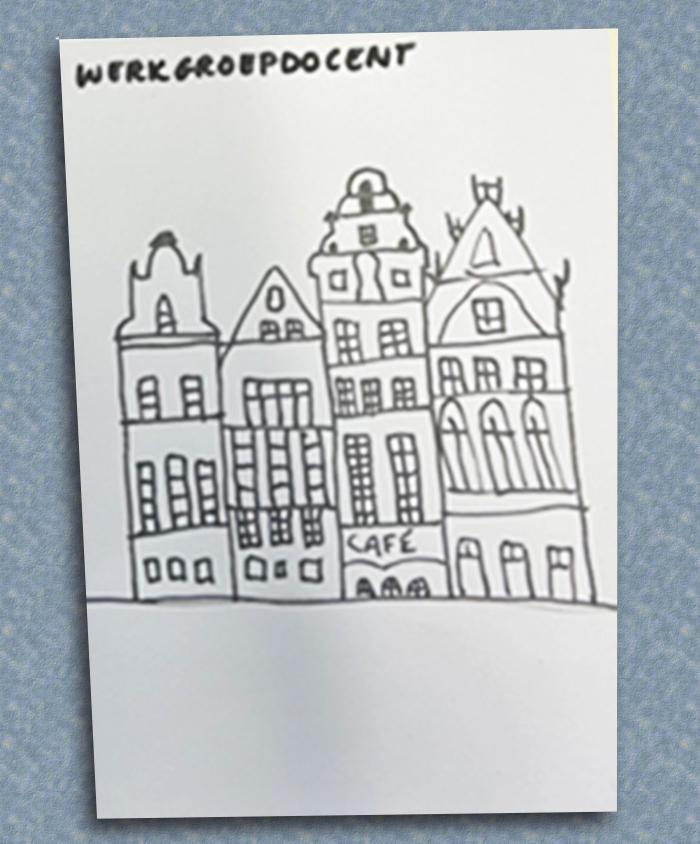

Finally, this format allows students to express personal appreciation for the teacher, almost like a thank-you gift. For example, one student drew the workgroup teacher's hometown:

Interaction between students 1 and 2 about the drawing above:

Student 2: “What did you draw?”

Student 1: “This is a square in [name of the city].”

Student 2: “And why did you draw that?”

Student 1: “Well, as you may know, [teacher's name] is [nationality]. [Teacher] is from [name of the city], if I’m not mistaken… So, I thought that was appropriate.”

Student 2: “This is a nice drawing.”

Student 1: “I’ve been there once. So, I thought: "Nice, huh, nice workgroup teacher. He was always, huh, always cheerful. Always happy, like a happy dad.”

Student 2: “You really wanted to draw this for [teacher], huh?”

Student 1: “Yeah, as a sort of thank you.”

[Transcription]

…And the disadvantages

However, there are downsides to this evaluation method too. First of all, this creative way of working is not for everyone. Some students found it difficult to draw their experiences and feelings, and/or translate the shapes they had drawn into words. Although the Dixit cards were a nice option for those who did not want to draw, choosing cards is different from drawing. Drawings are often free associations based on metaphors, while cards help students get started with associating. There were also differences between teachers. One of the teachers emphasised the optional nature of the evaluation assignment, which resulted in a significant number of empty submission folders. In contrast, teachers who presented the evaluation as an activity that was part of the class obtained a much higher number of drawings and recordings. Nevertheless, even in groups with fewer submissions, debriefing the assignment led to a lively, detailed discussion about the course.

Another disadvantage is that this evaluation method is more privacy-sensitive than Caracal evaluations. After all, the conversations between students are more personal and easier to trace than the evaluations submitted through Caracal. The data must therefore be handled with care.

Thirdly, the recordings must be transcribed and analysed automatically, at least in part. Otherwise, it takes a long time and it is difficult to make sense of them. A student assistant is therefore indispensable, but that costs money.

A fourth caveat is that the evaluation form yielded many free reflections, but only managed to elicit limited reflection from students on their own role in the learning process. Most students stuck to the proposed format and did not discuss other topics in their conversation. Only a few thought about their own roles. If teachers want information about certain topics, they should ask specifically about them as even a free format such as this one does not automatically elicit that.

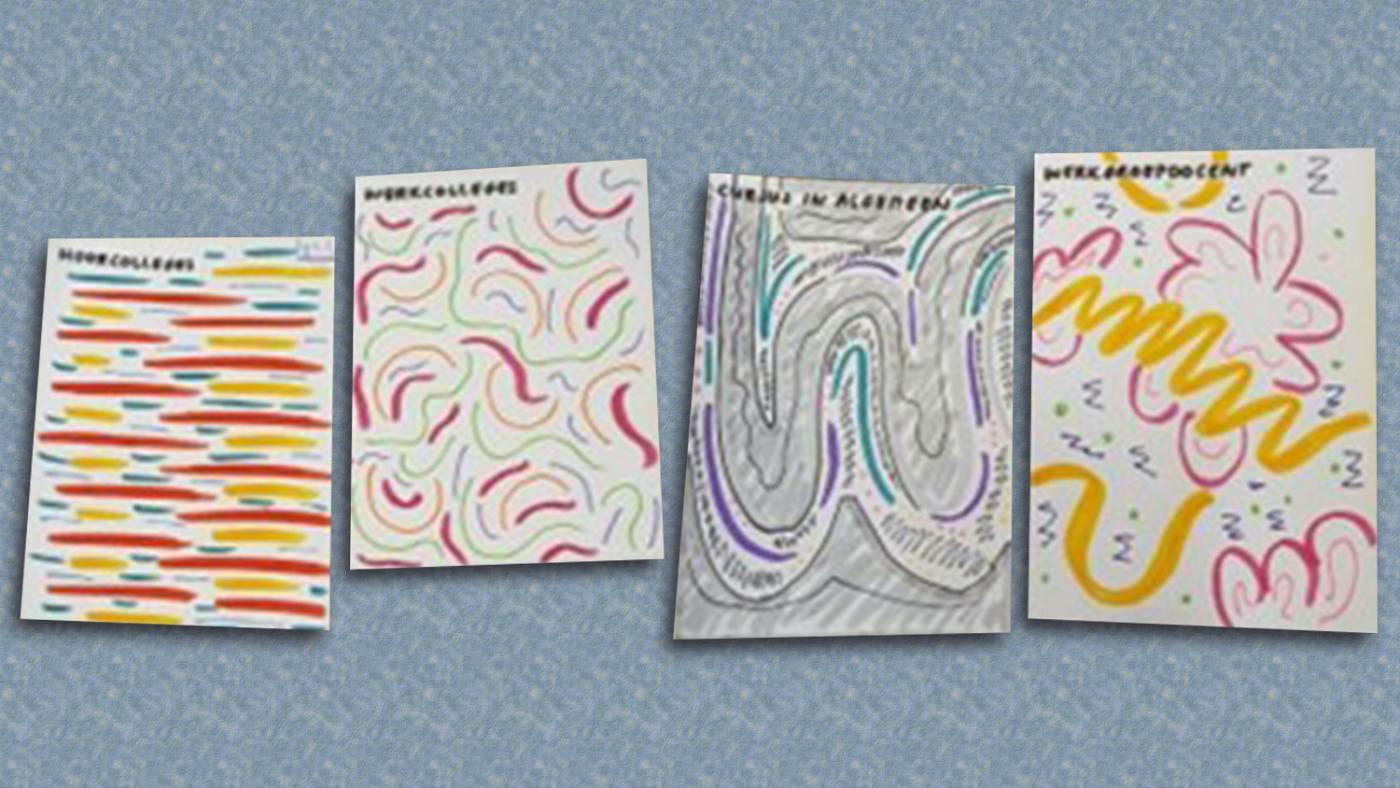

Finally, in practical terms, this experiment required a significant time investment for both students and teachers. For instance, a drawing alone is often not enough to interpret the content of a conversation. Take the drawings below. It is hard to interpret the student's intentions without listening to the recording.

Student explanation of the drawing below:

“She always went through it so quickly. You really had to keep up and, like, type along. It is red too, because, content-wise, it was clear and explained well.”

[Transcription]

Not suitable for a large-scale approach

All in all, this evaluation format provides a lot of valuable information, but interpreting and processing that information is costly. Therefore, this method is not suitable for a large-scale roll-out due to the time investment it demands of all those involved. However, it does contain positive ingredients for various purposes: for example, it could work well for teachers looking to engage in teacher professionalisation activities or those looking to get closer to students, hearing what they mean by comments like "This teacher creates a pleasant atmosphere" (or something else).

This format does take time. One could only use the association cards, asking students to associate them with two or three questions or themes devised by the teacher. In small groups, students would explain to each other in 10 to 15 minutes why they chose certain cards. If there is no time or resources for anonymously transcribing the conversations, students could be asked to write down a summary of their conversation or submit one digitally.

For minor or training coordinators, this method (along with the recorded conversations) could provide useful information that would make the time investment worthwhile.

It does not work for training committees or management, who would like to be able to compare it with a course from last year or other courses. Due to the intensive method of data collection and data interpretation, this qualitative form of evaluation is not suitable for quick comparison. It is a choice between so-called objective, comparable but meaningless scores or subjective but detailed and nuanced stories.

We noticed that it is a nice way for students to tell something about the course or the teacher. To make the feedback interpretable, provide the drawing or association map with an explanation. The teachers involved appreciated the input and found it valuable for the design of their next courses.

Read more:

De la Croix, A., & Veen, M. (2018). The reflective zombie: problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7, 394-400.

Esarey, J., & Valdes, N. (2020). Unbiased, reliable, and valid student evaluations can still be unfair. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), 1106-1120

Fawns, T., Aitken, G., & Jones, D. (2021). Ecological teaching evaluation vs the datafication of quality: Understanding education with, and around, data. Postdigital Science and Education, 3(1), 65-82.

Van der Schoot, M. (2020, juni). Een onderwijsevaluatie past niet in een vragenlijst. Available at https://www.scienceguide.nl/2020/06/een-onderwijsevaluatie-past-niet-in-een-vragenlijst/