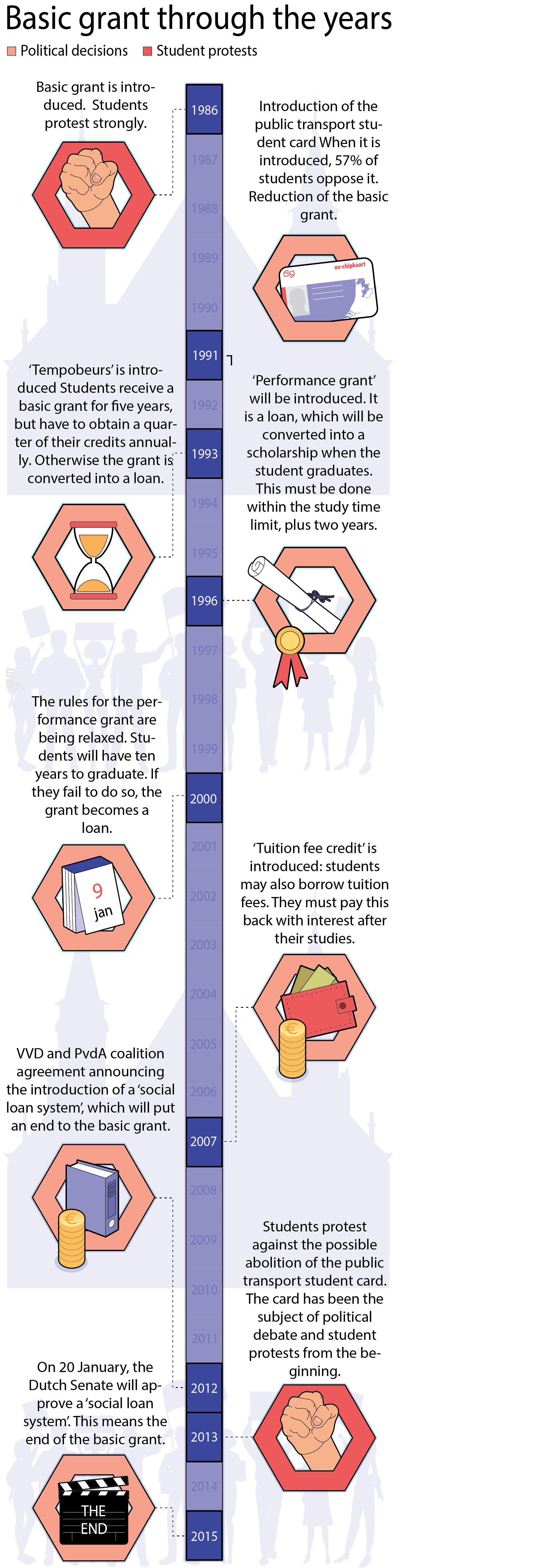

This is how the basic student grant was abolished

Beaten, disappointed, and mostly dead tired. That's how representatives of higher education students and shool pupils were after months of meetings, protests and discussions that culminated in a tense debate lasting almost fourteen hours at the Binnenhof (the seat of the Dutch government). The decision was made at 11:37 pm on January 20th, 2015: the basic student grant would be put to an end and an income-contingent student loan (sociaal leenstelsel) would be put in its place. “This bill is passed by 36 to 29 votes”, declared the chair of the House of Representatives, Ankie Broekers-Knol.

“We were at the Binnenhof very early that morning to watch everything happening at the public tribune”, recollects Tom Hoven, then chair of the National Student Union (Landelijke Studentenvakbond or LSVb), who currently serves as a spokesperson for the Netherlands Enterprise Agency. “We didn't expect the debate to end that way, even though we knew we'd started with a significant disadvantage. I know for sure that we, the civil servants who were involved, and the Minister of Education, were very nervous about what would come to pass. Afterwards, I finally went to bed in a hostel in The Hague at three o’clock in the morning, tossing and turning from tension and disappointment.”

Imagine, at 17 years old I was in direct contact with the chair of the House of Representatives

That disappointment is still fresh in the memory of Andrej Josic, then member of the National Pupils Action Group (LAKS in the Dutch acronym). “To me, the biggest shame was that the period in which we followed the debates and discussions came to an abrupt end. We travelled endlessly around Amsterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht for meetings with the unions. We used to meet in a fast food chain at the Binnenhof. Imagine, at 17 years old I was in direct contact with the Chair of the House of Representatives, Anouschka Miltenburg, and I had the mobile numbers of a lot of politicians. We were even allowed to read some of the papers before they were discussed in the House of Representatives. That was so impressive.”

A few months prior, Josic, on behalf of LAKS, was seated at a table with the then Minister of Education, Jet Bussemaker. The unions were allowed to see the proposal for the loan system before it was sent to the House of Representatives. “I was there on my own. A stupid move, as I had never seen a parliamentary bill before. It was a pile of papers full of legal terms and interest rate calculations. Now I would be able to read it, but at the time I just looked raptly at Bussemaker, who was sitting before me. When I was asked for my response, I said ‘I am in full agreement with the LSVb’. That seemed to be the best answer.”

"Keep your hands out of basic grant", says one of the signs carried by Vidius in a protest on the Malieveld on November 14, 2014. Photo: DUB

Tom Hoven used the same meeting to invite the minister for the demonstration against the loan system, set to take place on the Malieveld on November 14, 2014. Hoven, who was then a Biological and Medical Laboratory Research student at Nijmegen University, walked over to his Eastpak rucksack, took out the invitation printed on an A4 piece of paper, and laid it in front of the minister. A civil servant asked if he did not want to read the bill first. His answer was “No, I don’t believe it is necessary.”

The first actions were playful and sweet. We sent all members of Parliament a blue piggy bank. At the time, the main argument against the loan scheme was that a considerable group of people would not be able to afford to study

Hoven firmly believed that an income-contingent loan scheme would be detrimental to future students, whatever shape it had. “We'd been having our doubts for a long time, considering not much was known when the plan was included in the 2012 government agreement. But, right from the start, my biggest concern was saddling young people with huge debts”.

The school pupils union was also busy discussing what they should do about that strange new loan system. “The student unions tried to convince us that it would affect the future of our constituency. In the end, we joined the protests. The first actions were playful and sweet. We sent all members of Parliament a blue piggy bank. At the time, the main argument against the loan scheme was that a considerable group of people would not be able to afford to study”, Josic recollects.

In hindsight, the action that had the best chance to save the basic grant was far from playful and sweet. The Minister of Education, Jet Bussemaker, was under pressure to pass the proposal for the loan system quickly. Postponing or suspending the debate in the House of Representatives at the end of October 2014 could have major consequences.

Protest sign referencing the Minister of Education at the time: "Loan scheme: it's not over... Jet". Photo: courtesy Folia

The student unions got to work with some of the political parties to prepare as many parliamentary questions as possible for the last round of questions. The main goal was to cause delays and suspensions in the debate, leading to its postponement and, ultimately, the annulment of the bill. “We made up the most ridiculously detailed questions, which we submitted with all sorts of minor changes. We really hoped that we could stretch out the case”, Josic remembers.

However, the unions and parties involved had not taken the work ethic of the Ministry of Education into account. A group of civil servants worked on dozens of pages to answer the 170 questions the night before the debate, so that Bussemaker could speed up the process in the House of Representatives.

***

It was clear that the basic grant was doomed years before this political endgame. The school pupils and students stood no chance, despite the piggy banks, demonstrations and tons of parliamentary questions. After all, there wasn't a single political party supporting the basic grant anymore.

That was one of his suggestions that got nowhere. But it did prepare the ground for the idea

Jasper van Dijk, a member of Parliament belonging to the Socialist Party, who served as spokesperson for education in the House of Representatives until 2016, remembers when the then Minister of Education Ronald Plasterk suggested, back in 2007, that it was about time to bid the basic grant farewell. “That was one of his suggestions that got nowhere. But it did prepare the ground for the idea.”

Protest in Amsterdam, in 1998, against the implementation of a basic student grant. Photo: Rob Bogaert

Lisa Westerveld, now a member of Parliament for GroenLinks (the Green Left party), recalls: “I had just become the LSVB's chair in 2007. The RTL Nieuws news channel called me one evening in October. I was in my sports clothes in the train from Utrecht to Nijmegen, going to a football training. They asked me to come to their studios in Hilversum as soon as possible. They would only tell me why once I got there. It turned out that some civil servants in the Ministry had leaked that they were calculating the amount of money that the new loan system would generate. That was huge news that night. It completely exploded.”

The following day, Westerveld received yet another urgent invitation, this time from the Ministry. The chair of the Dutch National Student Association (ISO in the Dutch acronym) was also invited. “Plasterk promised us that he would not mess around with study financing during his term in office. I think he was shocked by all the commotion. Not much later, it turned out that one billion euros were needed for the teachers, so I think that his civil servants worked on several different scenarios to see how they could get that money.”

The left-wing political parties tended to have more idealistic reasons to bring up the basic student grant as a theme for discussion. They believed that most of the money would end up in the hands of students with rich parents who could afford to study anyway, with or without a grant. As for the right-wing parties, they wanted to abolish the grant in order to diminish the role of the state and lay the responsibility to finance their studies on the citizens' shoulders.

The banking crisis of 2008 and the subsequent economic recession were part of the reasons which led the second cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte, which took office in 2012, to come up with drastic cutbacks

The pivotal point in favour of the loan system, as is often the case, was money. Or rather, the lack thereof. The basic student grant had become unaffordable because the number of university students kept increasing year after year. The banking crisis of 2008 and the subsequent economic recession were part of the reasons which led the second cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte, which took office in 2012, to come up with drastic cutbacks. The cabinet aimed to ‘divert’ the flow of 16 billion euros elsewhere. The country had never needed such a crisis management before, but now it did and it needed it fast.

Higher education could not be economised as the increase in the number of students had scraped the bottom of the barrel. Money was needed to retain the country’s top position internationally -- an argument heard all around, including at the Veerman Committee, with the loud approval of universities, universities of applied sciences and several political parties.

***

"An income-contingent student loan will be introduced in higher education, replacing the basic grant for the Bachelor's and Master's levels. The new measure will take effect on September 2014. To guarantee access to education, the supplementary grant will fall outside the loan system", stated the announcement made on the coalition agreement issued in October 2012 between the VVD (People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) and the PvdA (Labour Party) -- an unlikely alliance.

Presentation of the government agreement, featuring Mark Rutte and Diederik Samsom (Photo: Government Information Service)

The hard renovation and economising agreement (named Bruggen slaan, or "building bridges"), which contained the announcement, was presented by the VVD and PvdA party leaders Rutte and Samson. In the background, a photo of the recently finished bridge at the Amsterdam IJburg. Not one word was said about future student debts. In the agreement, the cabinet’s resolution for abolishing the basic grant was labelled "From good to excellent education".

However, VVD and PvdA needed the support of the opposition for some of their plans, as they did not have a majority in the Senate. The first proposal loan system proposal, made by the Minister of Education Jet Bussemaker, did not get it, partly because it was unclear where the savings made possible by the cutbacks would end up. Jasper van Dijk (Socialist Party), who was against the abolition of the basic grant, said at the time: “For a while, I hoped that postponement would lead to the issue being dropped, but that did not happen.”

In my mind, the students were victimised by the fact that GroenLinks wanted to show that they were capable of governing and that the party dared to take responsibility.

When asked which party was responsible for making a proposal that did have the political majority ultimately end up on the table, most of those involved point to GroenLinks. This could have happened because of the addition of what was seen as a couple of cosmetic changes such as raising the supplementary grant and naming a recipient for the monies generated by the cutbacks. Van Dijk says that “Duisenberg of the VVD and Jesse Klaver of GroenLinks – and later Mohammed Mohandis of the PvdA and Paul van Meenen of D66 – made an agreement at Duisenberg’s house while sitting beneath the terrace heater. In my mind, the students were victimised by the fact that GroenLinks wanted to show that they were capable of governing and that the party dared to take responsibility.”

Lisa Westerveld and Janós Betkó are fully prepared to confirm that their party wanted to take responsibility. But they do not agree with the idea that GroenLinks single-handedly shelved the basic grant in favour of the loan system. Betkó, currently a blogger and policy advisor at the University of Nijmegen, has been involved in the party for years. “If you compare it to the election programmes of 2012, you will see that no single party actually wanted to invest money in higher education. The Socialist Party hoped to remove hundreds of millions of euros from the universities because they believed that education would cope with fewer managers. The CDA (Christian Democrat Party, in the Dutch acronym) did see something in a loan scheme for the Master’s phase and in being more stringent with public transport rights. That affected students heavily too.”

Lisa Westerveld (Photo: Lindora van As)

According to Westerveld, “there had to be a lot of economising. Now too, I see that there is no majority in the House of Representatives for investing in education. That is painful, but it is the reality.” As a matter of fact, both she and Betkó took the usual route to become active in the party: the student union LSVb. GroenLinks had been a supporter of the study tax for years. That's a system in which you pay more income tax if you have gone through higher education. LSVb, the PvdA and GroenLinks devised this plan in 2003, but Westerveld and Betkó still support it.

The pair even fought to retain the basic grant, they say. GroenLinks’ Programme Committee came up with a proposal to replace the basic grant with a loan system in the run-up to the 2012 elections. Betkó: “The Education Working Group was against this and wanted to submit an amendment at the party congress. I was abroad, so Lisa would explain the amendment at the congress.”

You collect notes from members at the congress. If you collect enough, you may present your amendment on stage. I had enough for about 45 seconds to explain why the loan scheme was a bad idea.

“You collect notes from members at the congress. If you collect enough, you may present your amendment on stage. I had enough for about 45 seconds to explain why the loan scheme was a bad idea. I talked about people’s fears in taking out loans, inequality and so on. After that, the party leader Jesse Klaver and someone from the Programme Committee argued why the loan scheme was a good idea.”

It seemed an even race at first. “Ultimately, I think there were only nine votes against our amendment. It was not even one percent of the 1,500 visitors or so to the congress,” recalls Westerveld.

“I was happy that it was not just a one-vote difference. In that case, I would have felt really bad. We knew that the party was divided, though the issue was not as decisive such as sustainability or peace missions. I understand the arguments for the issue at the macro level. A basic grant takes money away from all members of society and gives it to certain people, the majority of whom will earn a lot of money later on. However, it really can go wrong at the micro level. Not all students will earn high salaries after studying, yet they too will incur huge debts if they want to study. Take student nurses, for example. The generalisation that highly educated people earn a high salary does not apply to them at all.”

Pieter Slaman believes that the fact that the basic grant in fact kept income differences going instead of reducing them, was always a stumbling block for progressive parties. The historian at Leiden University earned his doctoral degree on this subject, in fact. Among his publications is ‘Staat van de student, Tweehonderd jaar politieke geschiedenis van studiefinanciering in Nederland’ ("The state of the student: two hundred years of political history in study financing in the Netherlands").

Higher income groups are overrepresented and the basic grant has only strengthened that

“Even today, higher education does not reflect the people. Higher income groups are overrepresented and the basic grant has only strengthened that. Many people seem to have forgotten that.” As a specialist in this area, Slaman sometimes gnashes his teeth when listening to the discussions. “The politicians and the people involved continuously talk over each other. One presents an economic argument, the other an education argument. In the end, there is no clear conclusion.”

***

By the time it was abolished, the basic grant was a mere shadow of what it once was. Slaman explains that “the first basic grant was very generous. You received a gift of 600 guilders (the Dutch currency at the time), on top of which was the actual grant. Hardly anybody borrowed any money. In the years thereafter, to put it disrespectfully, students were ripe for the plucking. Little by little, the grant was nibbled away.”

Almost every political movement could attach its own story and argumentation to the abolition of the basic grant. This gave the government a great window of opportunity to push the proposal through. Both the PvdA and GroenLinks argued that abolishing the basic grant would finally bring an end to subsidising higher incomes through study financing. For the VVD, the cutbacks would generate one billion euros, and thinking about this money, D66 saw its desire to invest in higher education fulfilled.

What about the students and school pupils? The Minister explained to them that, while they would not be entitled to a basic grant anymore, they would soon get better education in return. In anticipation of the millions freed up from the basic grant, universities and universities of higher education promised that they would free up 600 billion euros from their often large assets over the next few years, by making their education more small scale and intensive.

Even the money that would be freed up through economising from 2018 onwards would be directly put into higher education. Graduates would spend up to 4 percent of their income in paying back the loans, and through their student representation bodies at all educational institutions would have a say in deciding how the basic grant billions would be spent. Who could possibly be against this?

In November 2014, only a couple of thousand students and school pupils demonstrated on the Malieveld in The Hague against the loan system. The House of Representatives had already passed the Study Loan Act (Wet Studievoorschot). The Minister of Education, Jet Bussemaker, called on the protesters to “not let themselves be driven crazy by made-up stories about the consequences of the loan system”. She then added that, in the 1980s, about 35,000 students protested on the very same Malieveld against the basic grant, when it was introduced. The Minister at the time was even kicked in the stomach by one of the protesters. Then student leader Maarten Poelgeest (now a politician affiliated with the GroenLinks party) even announced that he would have signed up for a similar type of student financing to the current loan system in a flash in the 1980s, as long as no basic grant would be introduced.

Other objections to the loan system were swept off the table. The so-called "fear of loans" that would jeopardise access to higher education was disproved by research carried out by The Dutch Institute for Social Research. The most important question – who should invest in the future, the government or young people – was not asked. By 2015, the welfare state was largely done away with and market forces, self-reliance and individual responsibility became key terms in politics.

Historian Slaman says that “on top of that, older people were always better represented in politics, by far. Students are also not viewed as a vulnerable group that is largely supported by the wider society. There is still an image of partying individualistic people who are no longer in for demonstrations.”

***

Nevertheless, at the end of 2015, Tom Hoven and other politically active students still had some hope that the Senate would throw a spanner in the works. As mentioned above, the Cabinet did not have a majority in the Senate and the students hoped that PvdA senators in particular would not adhere to their party’s standpoint and would vote against the loan system. That had happened before.

Tom Hoven during the protests on the Malieveld in 2014. Photo: LSVb

Even now Hoven is unable to take a neutral stand when looking back at the students’ lack of willingness to protest. Why were there no large-scale student protests? “It is difficult to say. In the case of the income contingent student loan, it was not about the core question of whether students were prepared to take on debt. They were already taking out loans. It was about the amount of debt. Even if they realised that they would lose their basic grants for years to come, secondary school pupils were not released from school in great numbers to go and demonstrate in The Hague.”

We believed that the future students should be informed in-depth, and we did not want vulnerable young people to give up their study plans

Andrej Josic: “A few dozen of our members were angry about this. But every time we organised something, we saw that our constituency was not motivated to join in. I started to seriously doubt if a loan system simply wasn't a relevant subject to the pupils. The worst thing is that, immediately after the political decision was taken, we were asked to explain jointly with the Ministry what the system entailed. We had a cursory investigation done which, according to the ‘De Telegraaf’ newspaper, showed that the vast majority of pupils had no idea what and how they would have to take out a loan. This angered the Ministry as it led to questions being raised in Parliament. But we believed that the future students should be informed in-depth, and we did not want vulnerable young people to give up their study plans.”

Looking back, these were all outpourings from the rearguard that had no chance, concludes Josic. “Our last attempt was to organise one more symbolic protest at Prime Minister Rutte’s Torentje (the Prime Minister’s official office in a special tower in the Parliament building). We had a bouncy castle in front of it with lots of poor and rich students and that was that.”

It is true that young people start accumulating large debts early on

As a university student, Josic never received a basic grant. He first went to the Erasmus School of Economics in Rotterdam. Now, he is pursuing a Master’s degree in Quantative Finance at the University of Amsterdam and lives in a friendly but messy student house in Amsterdam-Zuid. “It may be the nature of my subject, but the issue of the loan system does not really come up now. In my first year, I borrowed a lot of money and did not work. I will probably be about 28,000 euros in debt in the end. That's not too bad. It's, of course, different for other people and it is true that young people start accumulating large debts early on. I still resent that. Our generation is already paying for everything that goes wrong, such as on the labour market and sustainability. And don't even get me started on the current corona crisis.”

“Once it happened, LSVb thought that every student would now see notable improvements in education. The money that was freed up from abolishing the basic grant comes from students and should be spent on students. A sector agreement was made to this effect, but if you ask me, there are few notable improvements", Tom Hoven adds.

Hoven paid for the tuition feed to study at a university of applied sciences with a basic grant. He does not want to justify his standpoint after the event. “I warned about the increasing debts, but I am not under the illusion that there was even one politician that did not know this would be one of the consequences. Even the House of Representatives took a conscious decision. It was apparently an acceptable risk.”

This article was made possible with the cooperation of Yvonne van de Meent, Laura ter Steege and Henk Strikkers.

This is the second article in an investigative series which was made possible by the Stimulation Fund for Journalism and various editorial boards at colleges and universities in the Netherlands. Read the first story here.