Professor Leen Dorsman reflects on his 45 years at university

‘It hurts to see more and more students talk about ‘going to school’’

The University Hall is like a second home to Leen Dorsman. He’s walking around there this morning. Study Association UHSK is organising the Holocaust Memorial Day in the main hall, an annual symposium that shines a light on a part of holocaust history. As a professor of University History and an honorary member of the study association, Dorsman attends every year, sometimes giving a speech as well. “Isn’t it great that students took this initiative and organise a conference every year? It’s a great example of how students contribute to the university’s community outside of their lectures.”

Dorsman will stand behind the lectern himself on February 17, to give his farewell address as professor. He’ll reflect on the past thirty years of university history, the time he’s spent working at the UU. “Not everyone will be happy about my observations,” Dorsman warns. He talks to DUB about his personal history, showing how it’s linked to the university’s history.

History students in 1977 protest on Kromme Nieuwegracht against the lack of space. A few years later, the course moved to De Uithof. Photo: Ublad-archief

Student years 1977-1985 Part-time jobs and parties in the basement

Before Leen Dorsman started studying History, he’d already completed the Journalism programme in Utrecht. “So I wasn’t a student who came straight from secondary school,” quite the contrary in fact. During his journalism studies, he married the woman he’d met in secondary school. “Thanks to a teacher, we managed to get a temporary studio. Later, when I was studying history, the home owner came to us to say he wanted to sell the building and that we had to move out. So then we bought it, for 58,000 guilders. The prices were low, but interest rates were high.”

Dorsman didn’t have a typical student experience. He wasn’t a member of any student associations, he didn’t join the student protests against increased tuition fees and the implementation of the two-phase structure. One thing that was typical for student life in those years, were the part-time jobs. “I must’ve worked everywhere. You’d take a van to Johnson in Mijdrecht, to pack wax products behind a conveyer belt, or to the Royco factory that produced soups in bags. In those days, students worked in those factories en masse.” He also regularly attended the popular dance parties held by study associations in wharf basements like the K-sjot.

Dorsman was, at times, active for study association UHSK. In those days, History was housed at the Kromme Nieuwegracht, at the corner of the Muntstraat. In his study days, the programme moved to De Uithof, along with Dutch and Slavic Languages, to the Centrum Gebouw Noord, which is now called the Sjoerd Groenman building. “Part of the Humanities faculty had to leave the city centre. That was not appreciated much. We felt like modern intellectuals needed the vibrant city centre life to function properly. American studies show that, too. I’m happy that in the late 80s, the decision was made to move Humanities back to the city centre.”

'Soon things will get serious' is the title of the article in the Ublad that includes this illustration. The story is about the forced departure due to the operation Taakverdeling i n the eighties Illustration: Ublad archive

The first job 1984-1994: from student assistant to temporary lecturer

The 80s weren’t the best time to study. The future prospects for recent graduates were poor, there was crisis everywhere, and the university was all about cutbacks. “During my studies, I got a job as a student assistant at historiography and the theory of history, that’s the science philosophy of history science. I was happy with it, and it decided my future. But it wasn’t self-evident. Everyone was tense. No one had job security. The Hague then came up with Conditional Financing. As a scientist, you had to indicate exactly what you’d done, and what you wanted to do. The idea was that that would lead to more national clusters of research. Utrecht could lose a few study programmes, as happened later with Dentistry and part of the Small Humanities programmes. But Pharmacy and Medicine were under pressure, too. Within a programme like History, I as student assistant had to fill out forms about what the scientists had published exactly. If you didn’t meet the requirements, you could get fired. You could feel the insecurity around you.”

The pressure from The Hague led to the entire university system changing. In his farewell lecture, Dorsman will argue that this was a turning point from the old-fashioned to the modern university. “Looking back, you have to conclude that it wasn’t that bad after all. Older scientists could retire early, even after the age of 55. And many researchers who didn’t have a PhD or didn’t have many publications, were forced to leave. That freed up space for young people.”

Dorsman got his job as temporary teacher as a result of this development. In that time, he obtained his PhD with a biography of G.W. Kernkamp, a famous professor of History of the Netherlands at the Rijks Universiteit Utrecht from before World War II. There was no option of getting a permanent position. “I never worried about it. You jump onto a moving car, and you go and see whether you manage to stay on it. Nowadays, people often see permanent jobs as a right. I never felt that way.”

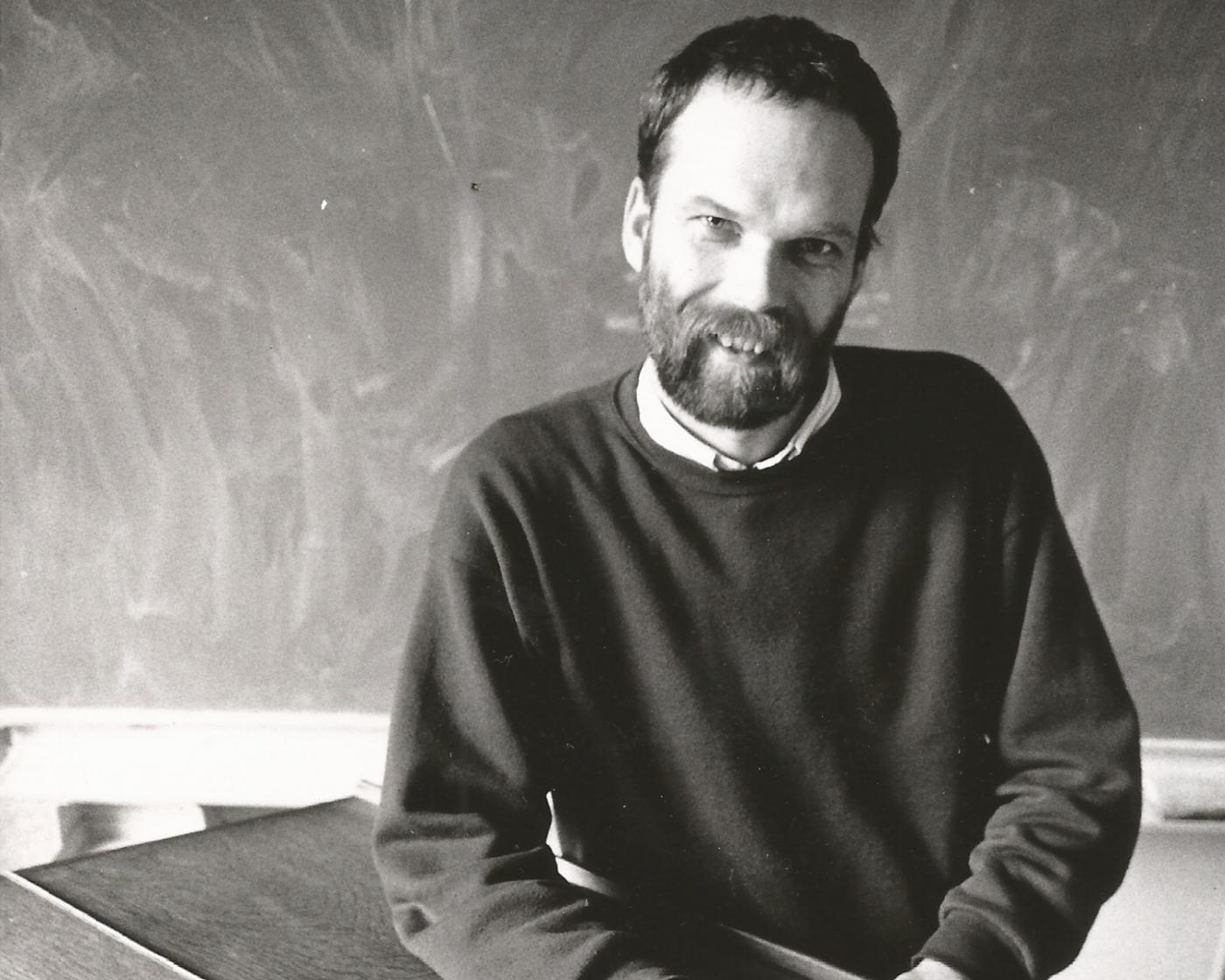

Photo of the teacher Leen Dorsman in 1991. Photo: Ublad-archief

Assistant professor 1994-2001: The new impetus of Harvard at the Rhine

The university had to reinvent itself, Dorsman concludes. What do we stand for? Administrators Jan Veldhuis and Hans van Ginkel set out to find a new impetus. The university board wanted to rid Utrecht University of its grey image. “They talked about Harvard at the Rhine in those days. People laughed at that, but they did have point, that the university needed a better image, and take its social responsibility.

“New programmes were introduced, like General Arts (‘Algemene Letteren’) and Social Sciences. The idea was that the labour market would mainly be looking for students who could prove an academic mindset, and they didn’t have to be specialised in one single discipline.

“They also introduced internships. The university is not a place that educates towards a single profession, but you can still ensure the gaps between studying and the labour market become smaller. Not everyone who studied history automatically became a teacher or a researcher. I spoke to someone who went to work at a bank, in loans. She told me her history courses had been so useful to her, because she’d learnt to look at data within context.”

Thanks to the many history courses at General Arts, Dorsman’s contract kept getting extended. At a certain time, he obtained a permanent position, and he ended up in the faculty board on an education portfolio, where he fought for a Humanities Project. That meant, for the first time, an alumni policy, that looked at where students ended up after graduating, and more attention to education within the entire faculty.

“It was an extraordinary time because minister Ritzen wanted to introduce the Mub, the Law of Modernising University Board Structures, which would increase the influence of the faculty board. The council structure was abolished. The old system had a faculty council with powers of co-decision, now they became advisors. The ‘vakgroup’ (discipline group), of which all lecturers were members, disappeared as well. Everything became more top-down. And I was there as a voluntary lecturer in the board. That was quite the challenge. You could tell the board needed to become more professional.

Professor 2001-2010: The introduction of the bama

In September 2002, the Bachelor-Master structure was introduced. The Bachelor would be a three-year programme, culminating in a diploma, and a Master’s would take one or two years, and would come with its own diploma. That also meant a new design for education. Dorsman: “The Educational Model in Utrecht had to ensure that academic education in Utrecht got into the spotlights more. Classes had to be smaller, courses had to be connected to each other better. For teachers, it meant less freedom. You couldn’t just make up a course about your own research topic. Some lecturers felt this limited them. I understood the change. A curriculum has to have cohesion.”

For Dorsman, education is important. He proudly talks of being named Teacher of the Year in 2000. He always took his first-year students to the university museum, to introduce historiography. He’d show the skeletons and ask: “What do you see here?” After taking a thorough look, there’d be a student who answered ‘misshapen skeletons’. Exactly – and then he’d link the misshapen, crooked skeletons to the scary diseases that sprung up as a result of the industrial revolution. And then the discussion would end with the question of whether you should be allowed to display a skeleton like that. What if this was a family member of yours?

“Education is reflection,” Dorsman says. “It hurts to see more and more students talk about ‘going to school’ and attending ‘class’ (translator’s note: there’s a difference in Dutch between the words for lectures/classes at university and classes in secondary school). No, the university isn’t a school that simply serves you the material you need to learn. It’s about learning to think critically, a place where you develop your academic consciousness. It’s a cosmos you need to live in. That’s why I sometimes took students with me to someone defending their dissertation. That way, they could experience how PhDs work. Most were fascinated.”

Leen Dorsman used to take his students to University Museum. Photo: DUB

Professor 2001-2010: The introduction of the bama

In September 2002, the Bachelor-Master structure was introduced. The Bachelor would be a three-year programme, culminating in a diploma, and a Master’s would take one or two years, and would come with its own diploma. That also meant a new design for education. Dorsman: “The Educational Model in Utrecht had to ensure that academic education in Utrecht got into the spotlights more. Classes had to be smaller, courses had to be connected to each other better. For teachers, it meant less freedom. You couldn’t just make up a course about your own research topic. Some lecturers felt this limited them. I understood the change. A curriculum has to have cohesion.”

For Dorsman, education is important. He proudly talks of being named Teacher of the Year in 2000. He always took his first-year students to the university museum, to introduce historiography. He’d show the skeletons and ask: “What do you see here?” After taking a thorough look, there’d be a student who answered ‘misshapen skeletons’. Exactly – and then he’d link the misshapen, crooked skeletons to the scary diseases that sprung up as a result of the industrial revolution. And then the discussion would end with the question of whether you should be allowed to display a skeleton like that. What if this was a family member of yours?

“Education is reflection,” Dorsman says. “It hurts to see more and more students talk about ‘going to school’ and attending ‘class’ (translator’s note: there’s a difference in Dutch between the words for lectures/classes at university and classes in secondary school). No, the university isn’t a school that simply serves you the material you need to learn. It’s about learning to think critically, a place where you develop your academic consciousness. It’s a cosmos you need to live in. That’s why I sometimes took students with me to someone defending their dissertation. That way, they could experience how PhDs work. Most were fascinated.”

WOinActie in front of the University Hall, april 2021. Photo: DUB

Department chair 2010-2022: Workloads versus recognising & rewarding

Neoliberalism has left its tracks in higher education. After the period of prosperity in the previous decade, Dorsman says a new period started with a corporation-like approach in which everything had to be justified in detail. Employees start experiencing more pressure, higher workloads, including because the number of students increases without corresponding additional funding.

“In the past years, I was department chair of the department of History and Art History. I’m a little ambivalent about this. I see the increased workloads. But it’s not a new thing that education takes up a large chunk of your time. You have a position with 70 percent education, and in practice, it’s often more. Research is something you have to make time for. There’s tension there. Don’t forget that education is an important task of the university. I’d love to see more possibilities for educational careers. People have been shouting that for years, but I can barely see any result in practice. Appointing a few research fellows isn’t enough.”

Around 2015, you see a movement start: RethinkUU, which fights for the old core values of the university. WOinActie is founded as well, a protest group which focuses on protesting the high workloads and the lack of funds in higher education. Dorsman has participated in a few protests. There’s significant financial pressure.

He also sees a different development. “When the Mub was introduced, the power of the administrators grew. The professor had more of a say again. For a long time, the senate hall didn’t have any portraits of rectors, but they returned in the 90s. But what you also see, is that that power can more easily lead to misconduct. Since #MeToo, you see how that position of power plays a role, and I don’t just mean sexually. In that sense, it’s good to see there’s more attention for Recognising & Rewarding, in which the research group has a more central place.”

Still, during Covid, Dorsman noticed that the new movement can take things too far sometimes. “Nowadays, apparently you’re not allowed to accentuate when someone’s done really well. As department chair, I regularly wrote newsletters during Covid. I’d mention good things that were happening in our department – whenever someone won an award, for instance, or when there were nominees for Teacher of the Year or Teaching Talent from our department. I was criticised for that. It was said to be too celebratory. I don’t agree. There’s also a lot of criticism from the woke people that came from the academic culture in the United States. It’s good to take a critical look at our own curriculum, but the tone is harsher there, and not as fitting for the Netherlands.”

Dorsman does think it’s a good thing that more and more international students come to Utrecht to study. “The world is global, and we want Dutch students to share their experiences in a classroom with students from other countries.” He refers to the Holocaust Memorial again, the one organised in the University Hall by UHSK. “That conference is in English, and they involve the international students, too. That way, you get broader discussions. That’s great, and fits well in academia.”