On the road with top rowing student Melle le Fevre: “We’ve got to win!”

Melle and I agree to meet on Saturday morning at 6.30 am at Triton in Kanaleneiland. It’s immediately clear to me why a career as professional rower would never work for me. I’m more likely to stumble into bed at this time than I am to rise. When I approach the deserted, dark, devoid of ambiance Driewerf wharf, I see three boys sitting there. If I didn’t know any better, I’d think they’ve gone out for the night, lost their keys, and are now waiting for someone to return home. In reality, they’re here in front of their training facility, waiting for the others. Later, I’ll learn that one of these young men is Jacob van de Kerkhof, winner of last year’s Varsity, who’s in full preparation for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

When Melle arrives, he immediately apologises. “The Saturday training sessions aren’t usually this early.” One of the men has to work, and now all sixteen rowers, four coaches, two scullers and I have to be in Vianen, where the training session is held, before dawn. On the way there, Melle enthusiastically talks about his preparations for this intensive training weekend, with a training on Saturday and a match on Sunday. “Last night, I was at an Indian wedding, and they really played this kind of music.” Then, I’m treated to his best attempts at Indian dance. The wedding, of course, could not interfere with his training. He went to bed early so he could still get enough hours of sleep.

During the training, I ask one of the coaches what he loves most about rowing. Without a second’s pause, he responds: “The boys’ commitment.” That commitment, I can see with my own eyes. They’ve thought about every single bite they eat. When I ask whether they don’t think that’s intense, they look at me strangely. Doesn’t it make sense that this is a part of your life? It helps you improve!

Melle knows like no other what it’s like to let your life be dictated by what you do and do not eat. Until recently, he was part of the ‘light rowers’ crew, and he had to be careful about his weight. On the days before the so-called weigh-in of the match, it’s of vital importance that you don’t gain a single gram. That this means spending time in the shower in a raincoat before the dreaded weigh-in, is just part of it all. Starvation is also a risk. Melle says: “Last year, there was someone from another club who had to lose 10 kilos in a week. When he tried that, he ended up in hospital with kidney failure, and now one of his kidneys doesn’t work anymore. The other remaining rowers joke: “At least that’s 200 grams you don’t have to carry around with you anymore.”

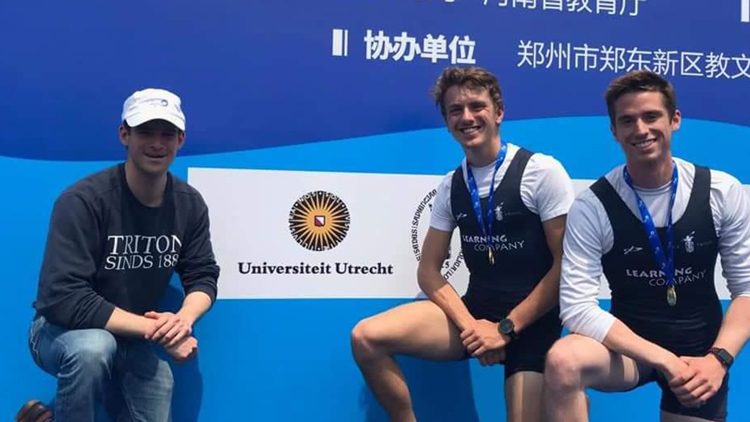

Melle - in het midden - na de prijsuitreiking van het studentenwereldkampioenschap

Now that he’s no longer a light-weight rower, Melle has some more freedom in his diet, but there are still other risks. There’s also the risk of becoming over-trained. On average, the boys train six to eight times a week. If you go too far in every training session, your body loses the ability to recuperate at some point. That’s a massive issue, and can lead to having to stay on the side-lines for a year. Generally speaking, they’re not too worried about this. Jacob, who only two weeks ago passed out during a match in Germany, responds casually: “You just have to keep a close eye on your body.”

The rowers aren’t all that worried about tomorrow’s match, but they are worried about the future. The subject of ‘training water’ is a recurring one. They’ve got the money, the knowledge, the people and the materials for the top level, but both the municipality and the university don’t do enough to facilitate the rowers, they feel. More bridges are being constructed over the Merwede canal, and from November on, they won’t be welcome in Vianen anymore either. There’s no clear solution yet, which frustrates the rowers, coach, and audience alike.

Match day

On Sunday, it’s time to see whether their hard work will be rewarded. They’ll fight for the Amstel cup, the first match of the season. It might not be the most important match, but the gentlemen of Triton’s ‘old eight’ would not have come this far if they didn’t want to win everywhere. They hope to get farther this time. The boys are in shape, and they know they are.

Competitive rowing is flirting with danger. Winning a match means pushing on when you’re actually exhausted, and training means rowing until you’re absolutely sick of it. For outsiders, that seems incomprehensible. Still, after the weekend, I understand why Melle and the others in his boat consistently push themselves so hard. You’re in it as a group. Although the personalities of the eight men vary wildly, they have one big thing in common: together, they’re chasing victory. Coach Niels is very clear in this: “The group is always the number one priority; individual issues come second.”

As the match continues and Triton gets farther, the short round evaluations become more intense. The boys can smell victory, and you can see it in their eyes. “We’ve got one job to do: win. Or we’ll be total idiots,” Melle says. It’s a great disappointment that they don’t manage to win the match. A small passing boat is named the cause of this. Frustrated, they discuss how the waves ruined their ‘push’ at 250 metres. Still, they don’t think of themselves as idiots. Until this time, Triton had never made it farther than the quarter finals, and now, they reached the finals. With justified joy, they bring in beer. Both victories and losses are shared together.

After eating hamburgers – “I’m going to load up on carbs, can I order two?” – I go home. My conclusion is clear: Melle and I study at the same university, did the same Bachelor’s programme, but live in completely different worlds. He and the people he hangs out with live for rowing. To me, the sacrifices Melle makes for his sport are too great, aside from the fact that I could only dream of having any talent for rowing. Still, I understand my former workgroup classmate well. Perseverance, discipline and ambition are things I’m not unfamiliar with, and testing your limits is a necessary evil that comes along with them. From the bottom of my heart, I hope that in Melle’s case, it won’t be for nothing, and that it’ll lead to extraordinary athletic achievements, including now that he’s in heavier weight rowing.