Truus van Lier: hero or murderer?

She is often referred to as Utrecht’s Hannie Schaft, but Truus van Lier, a female member of the Dutch resistance against the German occupation during World War II, is still hardly known outside of Utrecht. But that may change very soon.

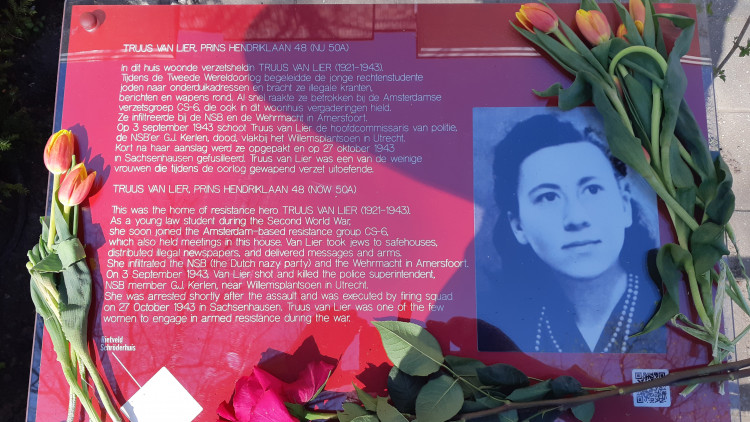

Last year, Truus would have turned 100 years old if she was alive. To commemorate her centenary, a plaquette was inaugurated at the Rietveld Schröder house. Members of the student association UVSV — with which Truus and her cousin, Trui, were affiliated — made an audio tour (available only in Dutch) about female resistance fighters in the Netherlands.

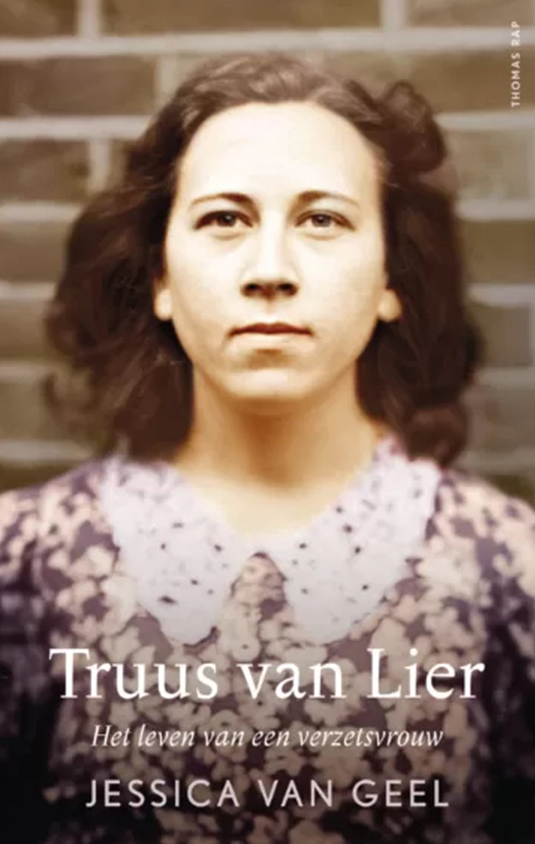

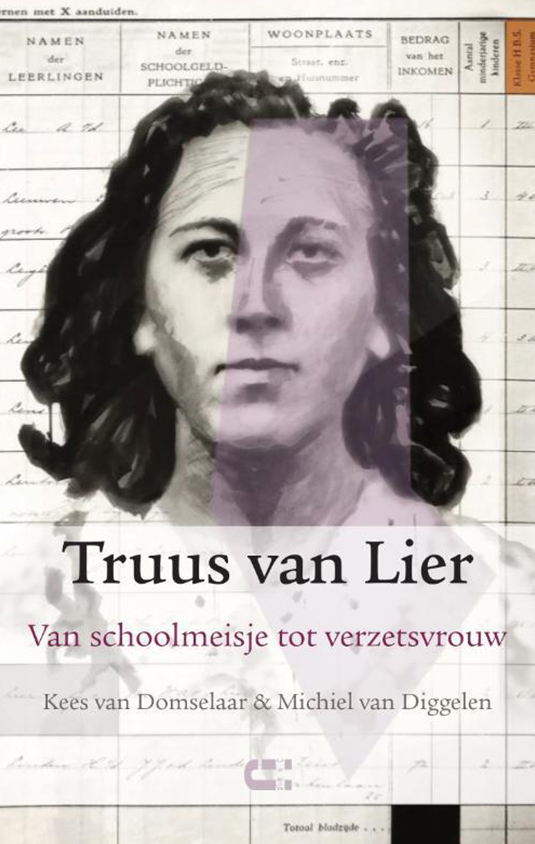

But it didn't stop there. Two biographies about Truus van Lier were published in April: Truus van Lier: Het level van een verzetsvrouw (Truus van Lier: the life of a female resistance fighter), by Jessica van Geel, published by Thomas Rap; and Truus van Lier: Van schoolmeisje tot verzetsvrouw (Truus van Lier: from schoolgirl to female resistance fighter), by Kees van Domselaar and Michiel van Diggelen. First published in 2019, the latter has been reviewed and republished by Dutch publisher Ijzer.

In addition, the TV show Andere Tijden broadcasted a documentary about Truus' family and childhood on April 11, paying attention also to her sister Miek and her cousin Trui. On April 22, Truus' birthday, a statue was unveiled in the Zocherpark, at the intersection between Walsteeg and Willemsplantsoen. That's where she assassinated Gerard Kerler, chief of police and a collaborator of the German occupation, on September 3, 1943. He lived nearby.

Perverse dilemma

Both biographies offer more details about Truus van Lier’s personal life. She was born on April 22, 1921, at Willem Barentszstraat, number 4, and grew up on Prins Hendriklaan, number 48, right next to the Rietveld Schröder house. Her family was highly educated, rich, artsy and liberal. Her father was Jewish.

From the start, the family was well-aware of the rise of Nazism and the threat it posed to Jews. Truus graduated from high school and went to Law school in Utrecht after the Germans had invaded the Netherlands. She joined UVSV and the Amsterdam-based resistance group CS-6, which was responsible for several assassinations.

Two of her family members, her sister Miek and her cousin Trui, worked for the resistance as well, though they were a bit more careful than Truus, particularly when it came to the use of force. Trui focused her efforts on Kindjeshaven, an orphanage located at Prins Hendriklaan 4, which she established in 1940. Thanks to her work there, she managed to save many Jewish children. Miek and her fiancé fled from the Netherlands in the middle of the war — she felt guilty for failing to take Truus with her for the rest of her life.

Truus, Miek and Trui’s convictions were strong, but the consequences of their resistance work were severe. The documentary aired by TV show Andere Tijden included footage of Trui who, decades after the war, still suffers from regular nightmares about her resistance work.

Truus went into hiding in Haarlem after the assassination of Gerard Kerlen, but she still got arrested. She was betrayed by CS-6 member Irma Seelig, who was forced into collaborating with the occupiers when faced with a perverse dilemma: her boyfriend was arrested too and she was told she would only be able to save him by collaborating with Truus’ arrest. Truus was deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, near Berlin, where she was executed on October 27, 1943, alongside two other Dutch women who served as resistance fighters. They were taken to Germany because executing them in the Netherlands would cause too much of a stir among the Dutch population.

Solid conviction Because Truus died so young and the most notable events of her life all took place during the war, it is easy to focus only on that period. But Jessica van Geel does a lot more in her book. She deftly employs a literary style to make events and people come to life. Convincingly using imagination and documentation, her writing is reminiscent of the historical works of Annejet van der Zijl and Stefan Hertmans. Readers get the feeling that they are there, in the scene, watching over people’s shoulders.

Because Truus died so young and the most notable events of her life all took place during the war, it is easy to focus only on that period. But Jessica van Geel does a lot more in her book. She deftly employs a literary style to make events and people come to life. Convincingly using imagination and documentation, her writing is reminiscent of the historical works of Annejet van der Zijl and Stefan Hertmans. Readers get the feeling that they are there, in the scene, watching over people’s shoulders.

On the one hand, Van Geel pays a lot of attention to Truus’ childhood and family members. On the other hand, she manages to make immediate cross-connections, like associating Truus’ birth in 1921 with the humiliation brought on by the Treaty of Versailles, one of the triggers of the Second World War. Truus' family moved houses when she was five months old, right when Hitler became the leader of the far-right National Socialist German Workers Party, Van Geel writes. Therefore, her way of writing provides a historical context that must have been all too present in the family's life.

Truus’ father also studied Law in Utrecht. An official photo of USC members from 1909 shows him as one of the proud board members. He was Jewish and, like many Europeans, very much aware of the dangers Hitler posed when claiming unlimited power, first in Germany and then in the rest of Europe.

But that sense of danger was probably felt way before that. Van Geel tells the story of Truus’ great-grandfather, who conferred with King Louis Napoleon in 1811. Napoleon asked him about his Jewish identity, snubbing him.

Van Geel's book also covers how the war affected the city of Utrecht, aside from the Van Lier family. Civil servants in Utrecht were replaced by Nazis or members of the Dutch Nazi party (Dutch acronym: NSB). That includes positions in the police. Many of Utrecht's residents got involved with the resistance movement, leading to arrests and mutual acts of retribution. Short chapters featuring several perspectives lead to a detailed, suffocating account of the assassination of Gerard Kerlen. Van Geel makes ample use of irony (nodding to the fact that we, the readers, know more about the outcomes than the characters) and is able to detail the event's background so thoroughly that the murder becomes inevitable, if only because of Truus’s solid conviction that her plan is right.

To her death Van Domselaar and Van Diggelen start and end their book at Christion Lyceum Zeist, the elementary school from which Truus graduated in 1940. Current pupils are taken on a school excursion to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where a teacher tells them about Truus, "an alumnus of Christion Lyceum Zeist". He ends their explanation by showing them the picture that is now on the cover of both books, likely taken in front of the school. She was "only a few years older than you", says the teacher, so that pupils can relate even more.

Van Domselaar and Van Diggelen start and end their book at Christion Lyceum Zeist, the elementary school from which Truus graduated in 1940. Current pupils are taken on a school excursion to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where a teacher tells them about Truus, "an alumnus of Christion Lyceum Zeist". He ends their explanation by showing them the picture that is now on the cover of both books, likely taken in front of the school. She was "only a few years older than you", says the teacher, so that pupils can relate even more.

Van Domselaar and Van Diggelen discovered some sharp details about Truus' school years too. She had to retake her Greek exam, which concerned a text from Plato’s Politeia that bears a lot of uncanny resemblances to the events of the summer of 1940. The anti-German Greek teacher provided a summary with the text: "Without a certain justice neither individuals nor communities can exist or function, even if they set an unjust goal."

Their story is more business-like and to the point. The drama of Truus’ story is not shown in their way of writing, but it is alluded to. They move quickly through the known, documented facts about Truus’ life.

They dedicate several pages to the events that pull apart the Van Lier family. In May 1940, an uncle from Truus' father's side, commits suicide alongside his wife. Then, her parents get a divorce, with the house being transferred to her mother's name only, while her father spent years in hiding at several addresses. Her mother didn’t survive the war: she was arrested when visiting Truus in prison shortly after the assassination, convinced that her daughter had been taken into custody unjustly. She was first deported to Kamp Vught and then to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she died in January 1945. Truus’ sister collaborated with the resistance movement from her hideout before fleeing the country. "I talked to Truusje for evenings on end, asking her to come with us. I told her: 'we’re going to die here'. But, as determined as she was, she answered: 'I’m staying.’" They saw each other for the last time at Utrecht central station.

Resistance fighter or murderer?

19-year-old Law student Juliëtte Meeuwsen served as a model for Truus’ statue. The documentary aired by Andere Tijden shows the process: Meeuwsen was photographed in the clothes Truus was wearing when she killed Kerler. She is also as tall as Truus, not to mention she resembles the resistance fighter in her posture and fierce glance. Asked to share her thoughts on the experience, Meeuwsen says that, although she was born in a different century, history suddenly seemed close and timely.

The documentary comes to a close by asking whether Truus deserves a statue or not. After all, she was not just a resistance fighter, but also a murderer. There is no answer to that, but the film ends with the image of a prototype of the statue, blood-red in colour.

There are no easy choices at war.

· Jessica Van Geel, Truus van Lier: Het leven van een verzetsvrouw, Uitgeverij Thomas Rap, 320 pages, € 26,98

· Kees van Domselaar & Michiel van Diggelen, Truus van Lier: Van schoolmeisje tot verzetsvrouw, Uitgeverij IJzer, 96 pages, € 17,50

· The documentary Drie vrouwen en het verraad is available online on Andere Tijden's website.

· Public broadcaster Ustad also aired a documentary about Truus van Lier, made by Edith Wegman.