Court sides with University of Amsterdam on use of surveillance software

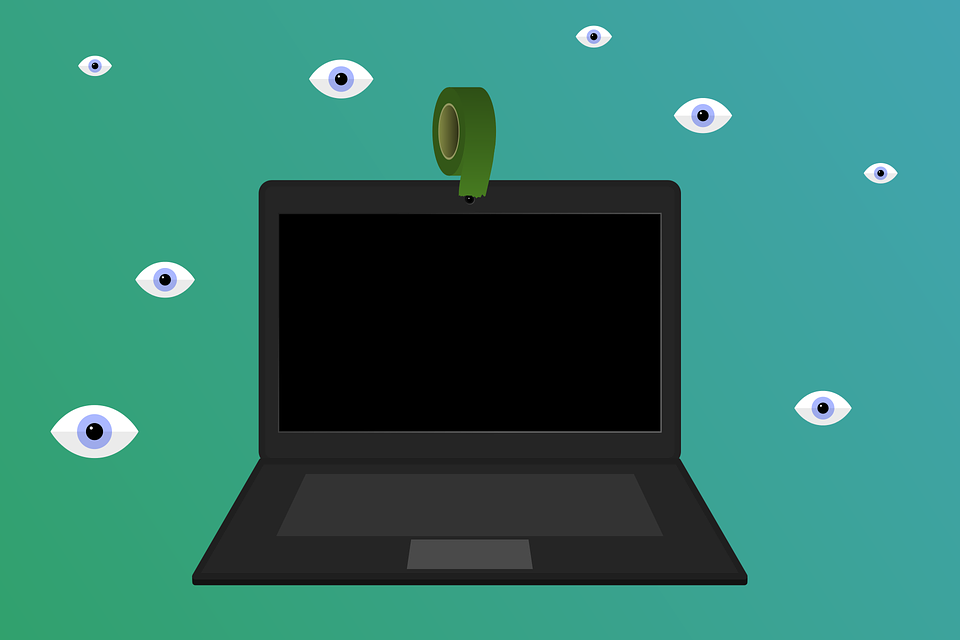

Like many other universities, UvA uses Proctorio surveillance software to prevent students from cheating on online exams by looking things up or sharing answers with one another. The program uses students’ webcams, microphones and browser activity to monitor them while they take their exam, and also tracks their mouse movements and keyboard use. Any suspicious activity is automatically reported, after which an invigilator can review the data.

According to the student councils, UvA should have first sought students’ permission before allowing invigilators to access their data. The national umbrella organisations for higher education participation councils supported this standpoint. In addition, the organisations argued that the use of this type of surveillance software is in violation of European privacy law (the GDPR).

Lawful use

The Amsterdam District Court thought differently, however, ruling that UvA’s use of online invigilation is not illegal. The Court’s decision was primarily based on the statutory examination regulations, which explicitly state that student councils have no right of consent when it comes to invigilation policies. This means that there was no legal reason for UvA to seek the councils’ permission.

The Court also ruled that UvA’s use of surveillance software does not constitute a violation of students’ privacy. UvA’s public task as an educational institution – to provide education, administer exams and award degrees – is laid down by law. As such, the GDPR allows universities to process personal data to the extent that this is necessary to perform their task. The Court agreed with UvA that the coronavirus measures require certain exams to be administered online, and that universities should make efforts to prevent fraud in doing so.

UvA’s handling of students’ data was also ruled to be GDPR-compliant: through its agreement with software provider Proctorio, the company was also bound to European privacy law. The Court further noted that the online surveillance process does not involve live monitoring – invigilators are only granted access to the data once the program has detected significant abnormal behaviour. Finally, the data is encrypted and automatically destroyed after 30 days.