Alongside scientists from France and Canada

Nobel Prize awarded to economist with Dutch parents

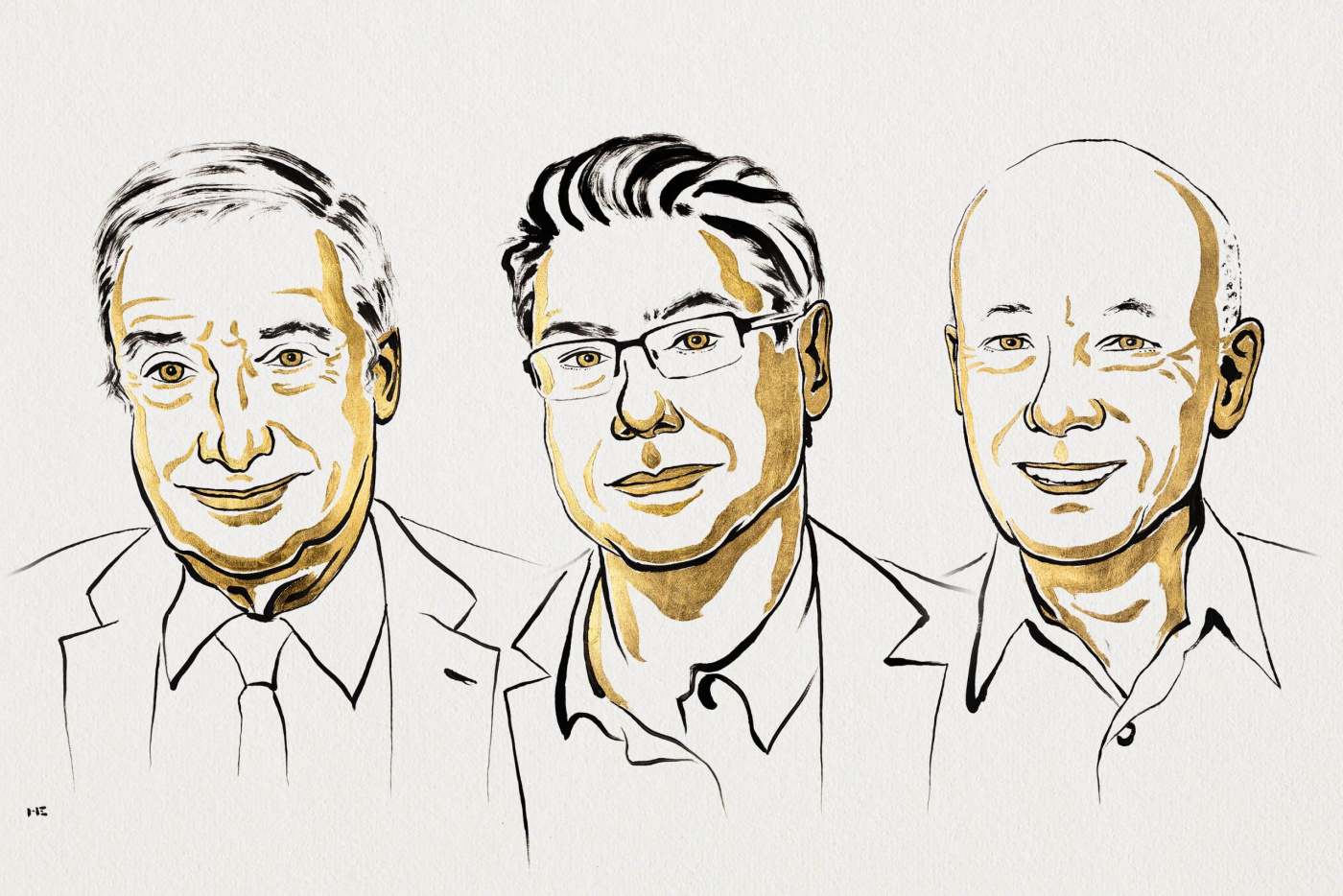

For centuries, the economy did not change much. The standard of living would hardly rise. Every now and then, a breakthrough of some kind would happen, but soon come to an end. In the two hundred years since the Industrial Revolution, the economy has grown more than ever before, thanks to technological innovation and scientific progress. These two elements reinforce each other and ensure a remarkably stable growth in the long term, according to economist Joel Mokyr, one of the winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics this year. Only a few economic crises, such as the Great Depression in the 1930s, have disturbed the upward trend.

Leiden

Mokyr is American-Israeli, and his parents are Dutch. In fact, he was born in Leiden, a city he visits often. His thesis at Yale University was on the history of the economy in the Netherlands.

His historical research, now awarded with a Nobel Prize, delves into the underlying mechanism of economic growth since the Industrial Revolution: useful knowledge that enters into circulation. This concerns knowledge about why things work, and how things work in practice.

Old products

The other half of the prize goes to the Frenchman Philippe Aghion and the Canadian Peter Howitt. In 1992, they presented a mathematical model for this process, in which research and development lead to “creative destruction”: old products disappear from the market due to the emergence of better ones.

They showed how R&D benefits society even more than it benefits the company that wants to innovate. After all, outdated knowledge loses all its value for a company, so investing in knowledge can sometimes be a risk. But innovations build on each other, so that outdated knowledge is still valuable to society as a whole.

That is why research subsidies can make sense from an economic point of view. On the other hand, even a small improvement to an existing product (which did not require much research) can quickly cause the old product to lose value. The idea is that innovation can sometimes go too far, in which case you need to subsidise R&D less.

Officially, there is no Nobel Prize for economics. This prize from the Swedish central bank was established “in memory” of Alfred Nobel and is also worth 11 million Swedish kronor (equivalent to one million euros).

The prize for economic sciences has only been awarded since 1969. Dutchman Jan Tinbergen was the first to win it, together with a Norwegian colleague. In 1975, Tjalling Koopmans shared it with a Russian economist. Three years ago, a third Dutchman won: Guido Imbens, together with a Canadian and an American.

We hebben natuurlijk niet zozeer economische groei nodig, maar een groei richting een duurzame samenleving. De daarvoor benodigde innovaties hebben deels andere dingen nodig, zoals een gedeelde duurzaamheidsambitie.