Seven percent of students dropped out

Pandemic over, student drop-out higher

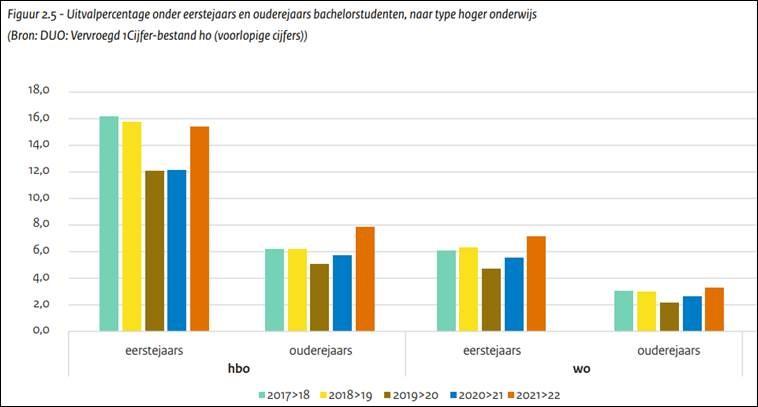

The number of freshers dropping out of research universities in the Netherlands increased the last academic year from around 5 percent in the coronavirus years to 7 percent in 2021/22. That is much higher than in previous years, when the drop-out rate was around 6 percent.

At universities of applied sciences the figures went from 12 percent in 2019/20 and 2020/21 to 15 percent in 2021/22, the same level as in previous years.

1.6 billion euros

The figures were revealed by a report about the National Education Programme, the aim of which is to combat the consequences of the coronavirus crisis in education. Higher education institutions received roughly 1.6 billion euros for this purpose in 2021-2023.

The drop-out rate among seniors has risen as well, especially at universities of applied sciences, where it went from 6 to 8 percent. The impact has not been as great at research universities. Right now, the drop-out rate among seniors is around 3 percent, roughly the same as before the pandemic.

During the pandemic, the institutions made changes to the binding study advice (BSA), which sets the requirements to continue on to the second year of studies. The changes were maintained in the academic year 2021/22 because of all the measures to contain the coronavirus.

Source: Third Report on the National Education Programme from the Ministry of Education. Image: courtesy of HOP

Additionally, examination requirements were relaxed in secondary education. In a letter to the House of Representatives, the Minister of Education, Robbert Dijkgraaf, and the Minister for Primary and Secondary Education, Dennis Wiersma, warn of the "flip side" of this decision: according to them, higher education students are “start their studies with lower and lower grades and less developed skills”, which, still according to the ministers, makes them “more likely to drop out”.

Allocation

According to the report, higher education institutions have now spent around 30 percent of the National Education Programme budget. It looks, therefore, like the allocation of funds is “up to speed”.

One of the areas in which the institutions are spending the funds is students' mental health. They are deploying additional student psychologists or offering more support to students with an impairment. “But the policy for certain groups, such as LGBTQI+ students or those with a migration background, is still inadequate”, the report says.

How much should they be spending, then? The government acknowledges that the education sector is struggling with that question. “An educational institution is not a healthcare institution. It doesn’t have the necessary expertise when the issues become tougher and more complicated”, the Ministers write. “Unfortunately, because of the problem of waiting lists, students don’t always get quick access to the right specialists.” They promise to get back to that.

The Ministers regard the pace of the allocation of funds as a good sign. They expect the institutions to have utilised virtually the entire budget by the end of 2023. However, the recording of the expenditure is not always in such good shape. “Unfortunately, not all the institutions have provided accounts in accordance with what was agreed”, the Ministers admit in the letter.

Work placements and residencies

The report also mentions problems with work placements. Teacher training programmes are doing their best to reduce the arrears caused by school closures, for example with a virtual-reality application that, in the words of the ministers, "helps with teaching classroom management skills”.

Medical students suffered many months of delay because residencies were not able to go ahead during the pandemic, and the waiting list was significant even before that. A survey shows that institutions have now created extra residency positions.

Nevertheless, large numbers of prospective doctors took a gap year after getting their Bachelor’s degree. As many as one in three skipped the academic year 2021/22 and did not start straight away on their Master’s programme. The report says that “the reason for this is unclear”.