Self-testing proves unsuccessful among students: will half a billion euros go to waste?

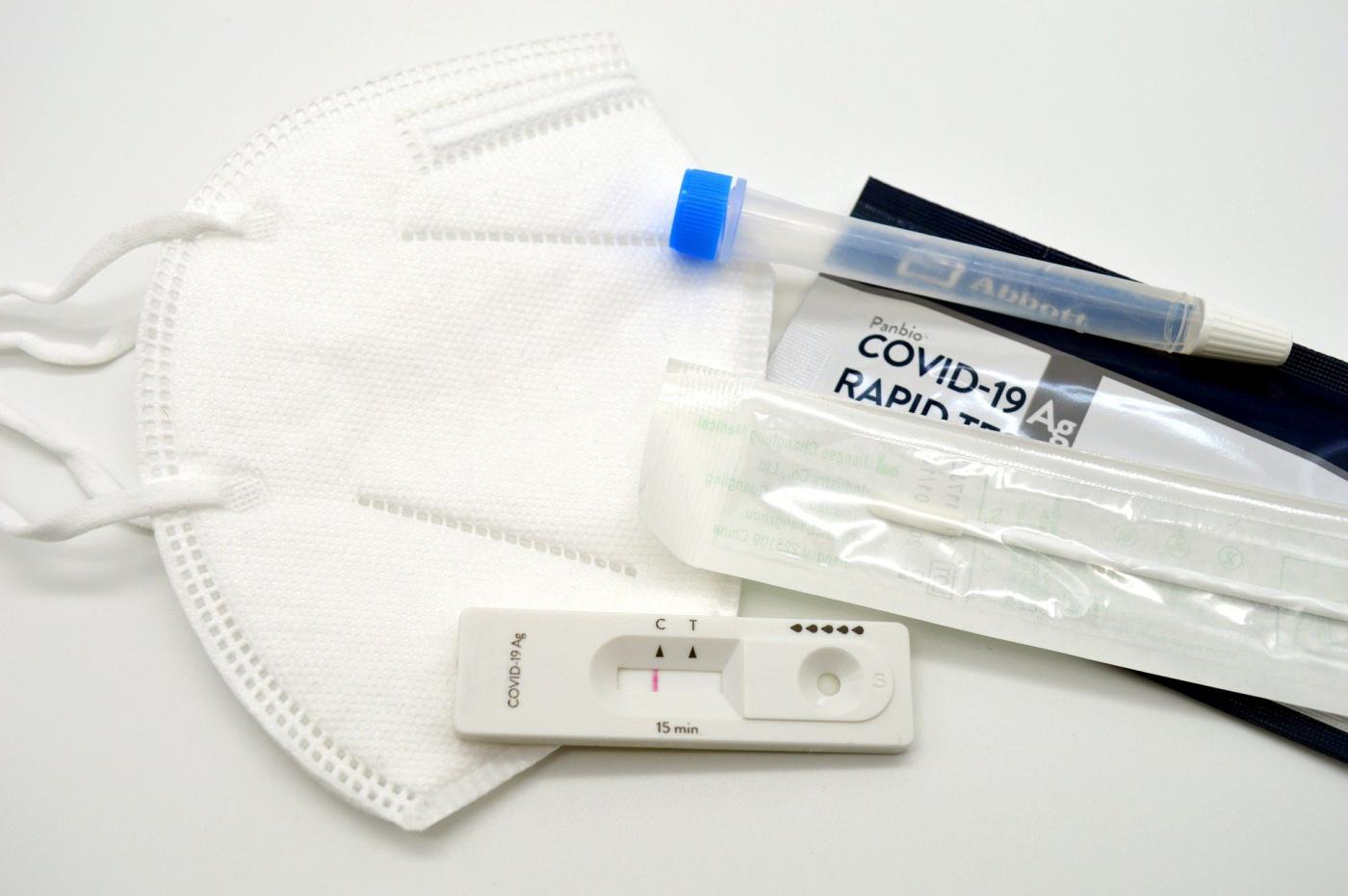

Avans student Lara is taking a self-test at home. She has her webcam turned on so test supervisor Gijs can watch her. She sticks the swab 2.5 cm up her nose, puts it in a tube containing a liquid and drips some of the liquid onto a small device. She now has to wait 15 minutes to get her results.

While it may all look simple enough, students are not exactly enthusiastic. The first results of self-test pilots conducted at Avans University of Applied Sciences, HAS University of Applied Sciences and Koning Willem I Polytechnic have been disappointing. Of the 1,400 students asked to take part, only 30 percent actually ended up participating.

No interest

No fewer than 20 percent showed no interest at all in the pilot right from the start. And of the 1,100 students who initially intended to participate, the majority did not show up at Avans’ online ‘test site’, where journalists had a virtual tour this morning via Teams.

Over the course of four weeks, more than a thousand tests were carried out, which yielded only one positive result. The student in question was asked to get an official test from their local municipal health service to confirm the result.

Lara, who studies biology and laboratory research, suspects that students just don’t see the point of self-tests. “There are no real consequences either way – there are no benefits to getting tested, and if you don’t take the test you can still go to class.”

Not mandatory

That’s exactly how the government wants things to be. Starting 26 April, students will be allowed to go to campus again one day a week – all thanks to self-tests, which are explicitly not mandatory. The programme will cost the government approximately half a billion euros, including distribution.

Considering the results of the pilot at Avans, this could end up being a waste of public funds. Avans is the first university of applied sciences to share their pilot results with journalists. So, what’s the initial verdict on voluntary self-tests without any form of coercion or reward? Project leader Carla Nagel chooses her words carefully: “This model doesn’t appear to be ideal.”

Jacomine Ravensbergen, vice-president of Avans, offers “some pragmatic insight”: “Self-tests aren’t really necessary to allow students to come to campus again one day a week starting 26 April. We also had students on campus in September and October. We’re perfectly capable of ensuring social distancing – all it takes is some forethought and nifty interventions.”

Far too low

A participation rate of 30 percent is far too low, says Ravensbergen. Students, she says, should be rewarded for taking a self-test. They could be allowed to come to campus more often, for instance, or to pair up with other students without having to observe social distancing. “They’ll start telling each other to get tested, and they won’t want to disappoint their friends.”

Whatever the solution may be, it’s clear that students need some form of incentive, according to Ravensbergen. “Because teachers want safety and students want proximity.” That’s why she’s pleading for new pilots which would make it possible to offer more freedom at educational institutions next September, at the beginning of the new academic year.

Plan B

But what would be the point of another pilot after most of the population has been vaccinated sometime this summer? Ravensbergen: “I expect that a lot of people will have had one or two jabs by September, and that will certainly help. But look what happened at the end of last summer – how many people brought the virus back with them to the Netherlands from their holidays. And we also have 16- and 17-year-old students here who are not eligible to get vaccinated at all. I still expect outbreaks, especially among young people.”

Project leader Nagel doesn’t want to rely solely on vaccinations either. “We need to have a Plan B. The virus has been one step ahead of us too many times.”