‘It was an adventure I would’ve loved to have missed’

Surely things won’t go wrong now, will they? That thought entered the mind of cultural anthropologist Marie-Louise Glebbeek when a grumpy ground stewardess at the airport of the South-Mexican city of Tapachula was unable to find a number of the paid-for tickets for her group. The final boarding call for their flight to Mexico-City could already be heard. Thankfully, a more cooperative colleague intervened and magically found the tickets in the computer system. “We had to run to catch the flight. Looking back, I think perhaps that was the scariest moment of all.”

That says a lot, considering Glebbeek had spent the past thirty minutes on the phone talking about endless difficult situations she experienced after Guatemala closed its airspace on Monday last week. At the time, she’d already been in Guatemala for a week to work on her own research, and was supposed to visit thirteen students who’d been doing fieldwork for their Bachelor project in Cultural Anthropology. Her cousin had travelled to Guatemala to accompany her, because travelling alone isn’t always safe there.

‘You could feel the atmosphere becoming more and more grim’

It all started with customs officers who wanted to detain her and her cousin at the airport of Guatemala City, after having visited the Maya treasures of Tikal in the north of the country. Then, lots of manoeuvres were necessary in order to collect all the students in a hotel in the nation’s capital; some students arrived exhausted after hours of travelling by bus. And then there was the situation at the airport, trying in vain to buy tickets, but only finding closed desks. And how she quickly started to feel that they should leave Guatemala as quickly as possible. “You could feel the atmosphere becoming more and more grim. Online, residents spoke very negatively about tourists as well. Even before the first corona patient was found –a Guatemalan citizen who’d contracted the illness in Italy.”

But there seemed to be no way out; they were stuck. “We were extremely bummed, of course, not in the least because the corona measures were becoming more strict. Very soon, we weren’t even able to eat in the hotel’s restaurants anymore; we had to eat in our own rooms. For that reason, I quickly devised some assignments to get the group working again. That worked, and the atmosphere remained great at all times anyway, no one complained or whinged. We were able to share emotions, for instance when the aunt of one of the group members passed away from cancer in the Netherlands, and she hadn’t been able to say goodbye.”

‘I realised early on that we had to try’

By then, she spoke to department head Kees Koonings at least twice a day. He was responsible for the more than seventy students in the Bachelor project, who were all trying to return home from various locations in the world. On behalf of the faculty, he promised all possible support. Glebbeek: “The students in Guatemala might’ve actually been in a privileged position. They had a group, and me as a teacher to fall back on. Others in similar situations didn’t have that. Right now, there’s still a student of ours in Bali who can’t leave. Hopefully, that student will be able to return on Friday.”

When more and more messages were shared in the app group ‘stranded Dutch people in Guatemala’ about people who’d successfully crossed the Mexican border, and Glebbeek’s UU colleague Gerdien Steenbeek – who’d been in Guatemala with her husband and sister for a personal visit – had reached Tapachula via that route, Glebbeek had to make a decision: stay or go. “I realised quite early on that we had to try. Especially since the airspace might well remain closed for much longer than two weeks. The Canadian and British embassies were already charting buses; what if we were the only ones left? Students started informing their parents. There was one student who hesitated and preferred to stay in a place she was familiar with, but after contacting her mother and sister, she agreed, too.”

‘To our surprise, a large ‘chicken bus’ showed up’

Through the Dutch consul, Glebbeek finally received a phone number for a bus rental agency on Thursday. “To our surprise, a large ‘chicken bus’ showed up, one of those pimped-out American school buses filled with glitter. Lots of noise, but at least we had sufficient space.”

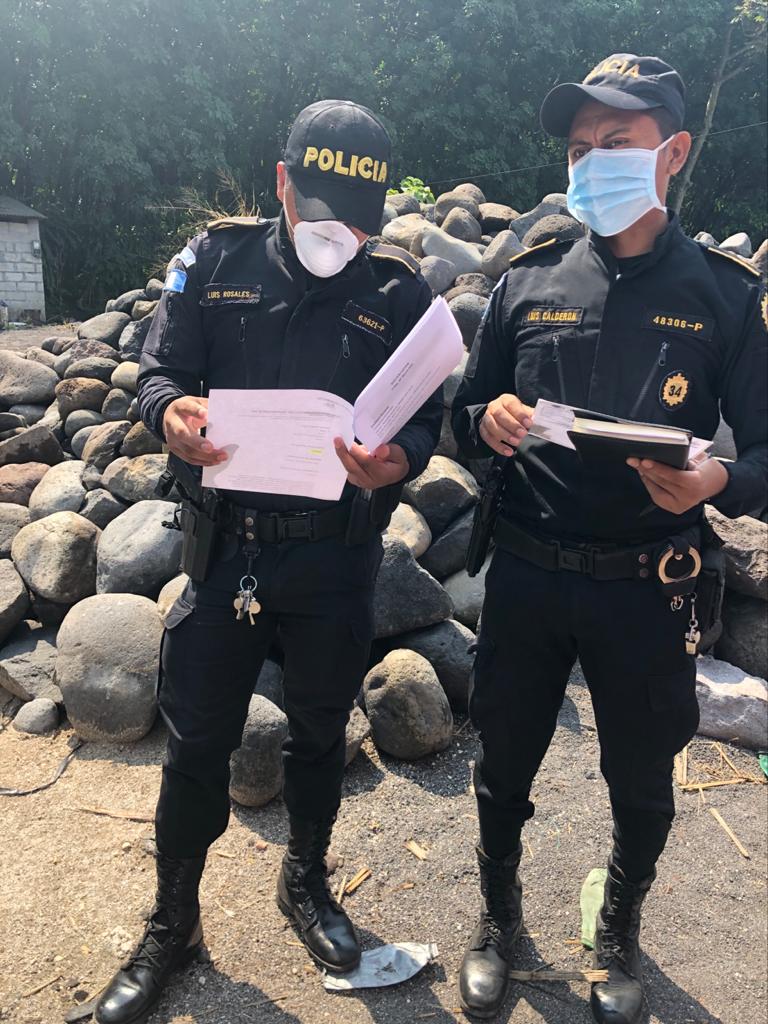

What followed was an arduous ten-hour journey, in which the promised guidance from the tourist police was regularly absent, and sometimes present. They had to stop no less than seven times for roadblocks set up by the National Civilian Police (PNC), who asked the driver to show his papers each time.

“I just stood closely to them each time and started obnoxiously photographing everything. I know how corrupt things can be there, and they prefer not to have anyone look at what they’re doing too closely. Thanks to my PhD thesis and my later consultancy work for the Guatemalan police, I have some contacts high up in the police force, whose names I mentioned.

“Thankfully, we were allowed to keep going each time, and crossing the border actually went pretty easily. My biggest worry was still my cousin, as she hadn’t been in Guatemala as long as us, and might be seen as a potential corona danger. But they took our temperature and aside from that, there was just the usual fuss of checking our bags and passports. Then, there was the question of how we were to reach Tapachula. That caused some trouble, because we didn’t have any Mexican money, but in the end, we were able to rent two vans with Guatemalan quetzals.”

‘I know how corrupt things can be here’

The entire time, Glebbek was in control mode. “Apparently, I function well in tense situations.” It wasn’t even the first time that she was responsible for a group in need far away from the Netherlands. “Before I started my PhD in Utrecht, I was a travel guide in Ecuador in 1998, when there was an enormous earthquake and a tsunami threat. After consulting with the embassy, I had to bring twenty people to safety.”

But this situation was of a different order. Moreover, she was worried about the wellbeing of her mother, who was bed-ridden with corona symptoms (“she’s doing all right now”). Her husband and two sons were also home. “They’re used to these things, I’m away from home for long periods quite regularly. But of course they also saw the impact of the coronavirus in the Netherlands, and didn’t know if everything would be okay. All in all, it was an adventure I would’ve loved to have missed.”

‘I always thought I’d be the last to return’

After safely arriving in Tapachula and reuniting with Steenbeek, they bought tickets to Schiphol. The parents of six students had bought business class tickets. One student was able to leave on Saturday; the others couldn’t leave until Thursday and Friday respectively, although they were put on a waitlist. “We did hope we’d be able to fly sooner, because of course many Mexicans weren’t allowed to leave the country. To me, the most important thing was figuring out who would leave first, as I didn’t want any cat fights. But we discussed it in the group and reached a decision together.”

After the stressful situation with the grumpy ground stewardess was over and they left Tapachula, everything went a lot more smoothly. Emotions ran high and the happiness was tangible when, after arriving at the airport in Mexico-City on Sunday, six students would be able to leave that same night, along with Glebbeek and her cousin, despite them being low on the waitlist. The other six who had business tickets would leave a day later. “That was quite conflicting to me. The entire time, I felt like I’d be the very last person to leave, so I could support the other students. But there was no other option.”

‘Catch my breath for a little while and then see about solving the chaos’

After the final group of students had arrived on Tuesday, and a large bouquet was delivered by the group’s parents, Glebbeek could finally exhale – but not too long. “I’m going to catch my breath for a little while and then see about solving the chaos. The students in Guatemala missed out on a large part of their fieldwork. And other students in the Bachelor project who returned earlier were awaiting instructions on how to continue. I wrote instructions for them in the midst of the chaos while in Guatemala. But we guarantee that we’re doing everything we can to ensure their study progress doesn’t get hurt.”

The one thing that they all feel (including the students), aside from relief, is sadness about the people they left behind in Guatemala, Glebbeek emphasises. “The students are worried about the host families they stayed with. They might experience financial difficulties now, but they’re also at a high risk of becoming ill. I’ve been visiting Guatemala for 22 years, and I know there’s huge inequality there. The rich have private clinics and can buy good health care, but there will be many deaths among the poorer population if this crisis grows. Within our group, we’re already talking about what we can do for the people there in the future. Things are definitely going to happen.”

‘In moments like these, all the tension comes out’

“On the one hand, it was a thrilling adventure. On the other, it was a week filled with uncertainty. Everything constantly went differently than we thought it would.”

That’s how Claudia de Jong looks back on that final week in Guatemala. Along with twelve other Bachelor’s students of Cultural Anthropology and their teacher Marie-Louise Glebbeek, she had to find a way home while the corona crisis was reducing their freedom of movement.

Claudia (on the left ) was in Guatemala to do research on the relation between Spanish and the indigenous language. She conducted interviews at markets and in stores in a village, and did participatory research: observing, talking, and assisting in work tasks. After the first corona messages came in, she originally decided to stay. She was having a good time. But in the end, that was no longer an option, when the university called back all its students abroad. “You started to hear more and more stories about how tourists were being seen as the people who brought the virus with them.”

Claudia (on the left ) was in Guatemala to do research on the relation between Spanish and the indigenous language. She conducted interviews at markets and in stores in a village, and did participatory research: observing, talking, and assisting in work tasks. After the first corona messages came in, she originally decided to stay. She was having a good time. But in the end, that was no longer an option, when the university called back all its students abroad. “You started to hear more and more stories about how tourists were being seen as the people who brought the virus with them.”

Claudia described her experiences on her travel blog, including about the group’s difficult decision not to stay in Guatemala, but to travel to Mexico across land. “I was like: Mexico? All right, let’s do it.”

But she, too, felt the relief when the group finally knew for sure they’d be able to fly home. “In moments like these, all the tension comes out. For everyone. It was such a nice, tight-knit group. And we had great guidance in the form of Marie-Louise.”

In the Netherlands, she found her worried mother, with whom she’d video called nearly every day, waiting for her. And now, she’s safely home with her parents in Wijchen. Still, she can’t wait to return to Guatemala. “I want to see those people again, and speak the language again. I was nowhere near done there.”

'We had to rush to pack our backpacks'

“The last week was confusing, everything happened incredibly fast.” Jelte Vegter was the only man in the group of thirteen students. He conducted research on ethnic identity formation and inter-ethnic relationships in the city of Quetzaltenango.

When the first calls were issued to return to the Netherlands, he hesitated. The Bachelor project was something he’d prepared for for so long; it’s the crowning glory of his study programme. On the other hand, he realised that the coronavirus would hit the poor country of Guatemala, with its abysmal health care, a lot harder than the Netherlands. “I had to choose between my heart and my head, and in the end, I chose to listen to my mind.”

The return tickets had already been booked, and they were to fly the next Thursday. But on Sunday, teacher Marie-Louise Glebbeek texted him to come to Guatemala City as quickly as possible, so they might be able to catch the last flight before the country’s airspace closed. “We had to rush to pack our backpacks and say goodbye to our host families.”

The return tickets had already been booked, and they were to fly the next Thursday. But on Sunday, teacher Marie-Louise Glebbeek texted him to come to Guatemala City as quickly as possible, so they might be able to catch the last flight before the country’s airspace closed. “We had to rush to pack our backpacks and say goodbye to our host families.”

A taxi took him and a few fellow students to the capital in a four-hour trip, but they were too late. For three day, the students were stuck in a hotel, before the decision was made to travel across land to the south of Mexico. From there, they flew to Mexico City. Jelte finally arrived in the Netherlands on Tuesday. “The whole thing, between hearing that I’d have to leave immediately and arriving home, took eight days.”

The moment that stuck with him the most was one that happened shortly before leaving Mexico City. “While we were standing around in a park, a man approached us, and told us in Spanish that we should wear masks or else ‘go infect our own country’. That says a lot, I think, about how many people’s feelings about tourists was shifting.”