Alex, from Russia: ‘I find it hard to talk to Ukrainians, I never know what to say’

When the war started, Alex couldn’t sleep for days, lost two holes in his belt and started smoking like a chimney, running down on the supplies of cheap tobacco he had brought from Russia, which were supposed to last for several months. He got laid off by the Russian IT firm for which he worked remotely to pay for his living expenses and part of his tuition fee in Utrecht. “About 70 percent of their clients were based in Ukraine”, explains the student. To make matters worse, he was deprived of his money for weeks.

Alex knew that criticising the government comes with a price, but he couldn’t stay silent. In his blog about Economics, written in Russian, he openly expressed his opposition to the invasion. “I’m privileged for being here and having freedom of expression. Not using it simply wouldn’t be the right thing to do.” The post gathered some 30,000 views.

But being fully aware of the consequences beforehand doesn’t make the pill any easier to swallow. “I love my country. At the end of the day, it’s my home. Realising I can’t go back is tough.” Especially since he was supposed to go to Perm in April to get married. His girlfriend of four years is now trying to find a job in the Netherlands to join him permanently. In the meantime, they’re doing their best to keep their hopes up.

If you really want to understand why and how this happened, it is not enough to read the news

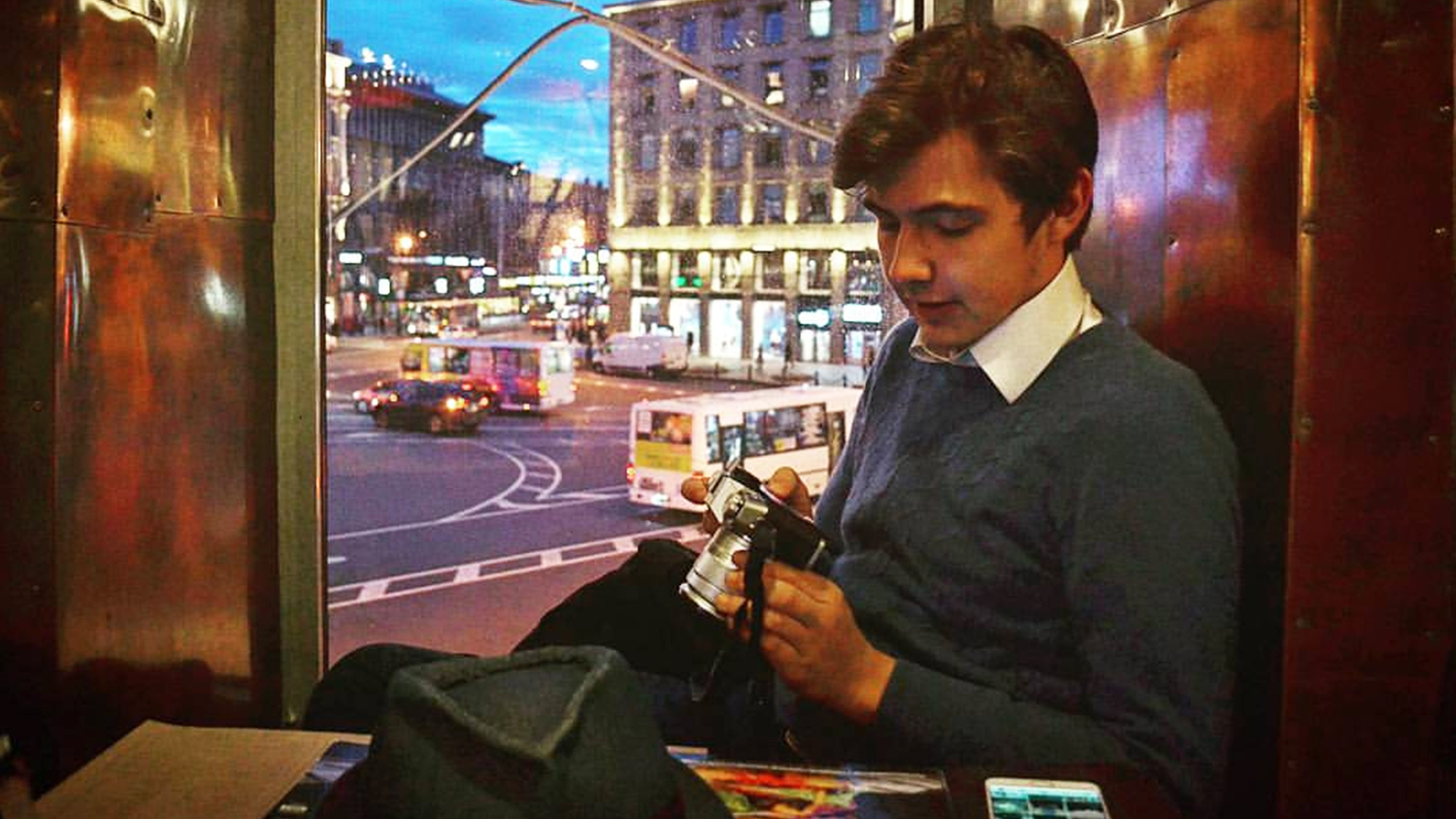

Alex in St Petersburg, his favourite city

Alex in St Petersburg, his favourite city

Following the news coverage from here, Alex is sometimes bothered by the lack of nuance and context. He cringes when journalists explain the conflict by merely saying that Russia resents not being an empire anymore.“That is such a simplistic explanation. If you really want to understand why and how this happened, it is not enough to read the news. You have to know the history of Russia and Ukraine”, ponders the student.

”For example, Western media complains about Russians supporting the war without understanding why that is. The majority of soldiers deployed in Ukraine do not come from big cities like St Petersburg, Moscow or Perm. Usually, they come from villages and small towns where they don’t have sufficient education, good jobs, and a nice infrastructure. So, the army is one of the very few ways they can get out of the village and climb the social ladder. The fact that they don’t have access to good education also means that they can be manipulated more easily, so support for the government tends to increase the more deeply you go into Russia.”

Talking to Ukrainians is a bit hard for him: “I never know what to say”. Andriy, the Ukrainian student interviewed by DUB in March, is Alex’s classmate in the PPE programme. Alex also has friends in Ukraine whom he met a couple of years ago in the UK. “Luckily, the war hasn’t changed anything about our friendship. But I’ve heard of Ukrainians who don’t want to talk to their Russian friends anymore and Russians who don’t believe what their Ukrainian friends say. That’s another sad consequence of the war.”

I would like to ask for a little bit more empathy

In his view, there are two wars going on: a physical war in Ukraine, which is killing and displacing millions of people; and an “intellectual war” in Russia, which is displacing people in a more symbolic way. “For those who are not supporting the war, even by the most moderate accounts, it’s difficult to come to terms with the fact that our country is doing this. It’s hard to live with all the laws that the government is imposing on us. So, we are basically left with no home. Of course, physically there is a home, but things are changing so rapidly and to such an extent that you stop recognising it as the home you know.”

“I’ve heard some people saying ‘how can Russians complain about sanctions when people in Ukraine are dying?’ My response to that is that many people in Russia are disturbed by the news and worried about the people in Ukraine. Lots of Russians cried when they read the news about the murders that occurred there. I don’t deny the suffering of Ukrainians, but one thing doesn’t nullify the other. We shouldn’t ignore the fact that Russians are being hurt by this war and all the sanctions. They are going through the hardest time in their lives. So, I would like to ask for a little bit more empathy.”

Alex with his girlfriend

Alex’s mother is a good example. Distressed by the war, the sanctions and all the new laws against those “with a big tongue”, as one says in Russian, she is considering moving to Bulgaria with Alex’s younger brother. Her business – a travel agency – is not in motion since the invasion anyway. “I told her to think this through”, he says. “My dad has to stay in Russia. He’s been working until 10:00 pm every day to make sure the family is well-fed and I can complete my education. I feel really sorry for him because, if this happens, he would come to an empty home at the end of the day.”

Alex’s father has a small factory employing six people. The logistics and payments of his company have been disrupted by the war because he has to buy equipment abroad. “When I call my parents, every day is different: sometimes my father sounds confident that he’s going to make it through the crisis, but at other times he’s like ‘I don’t know."

The student is concerned about losing his second chance at getting a PPE degree: two years ago, he was following a similar programme in the UK, but the pandemic forced him to go back home. The decision to start over in the Netherlands was financially-motivated: a PPE degree is cheaper in Utrecht, compared to the UK, even though he pays the institutional fee, which is much higher than the one paid by students from countries in the European Economic Area. However, if his parents go bankrupt, he cannot pay the tuition fee all by himself.

My plans are getting narrower and narrower

The circumstances have forced him to readjust his hopes and dreams. “My dream was to get a Bachelor’s, a Master’s and a PhD, then win the Nobel Prize in Economics”, the student says. “Now, I hope to finish my Bachelor’s and then get a certificate in Data analytics so I can find a job that would allow me to stay in the Netherlands with a work visa. If everything goes well, then I can get a Master’s and a PhD at some point. But, you see, it’s getting narrower and narrower.”

Alex when he was studying in London

Alex when he was studying in London

Even so, things are looking up. In the first few weeks of the war, when his financial situation was dire because he couldn't transfer money from Russia, he was lucky to be able to count on his flatmates’ understanding. “They didn’t say anything, but I noticed they started buying all the common things, like kitchen towels and toilet paper, without asking me to chip in. One person from my course was even willing to just give me food.” Alex says that other people’s support is what got him out of his chainsmoking, sleep-deprived existence. When DUB spoke with him in mid-May, he was about to start as a student assistant at UU, a job he got through the PPE programme.

He also found a way to access his funds. Alex has been transferring money from Russia to the Netherlands in a rather intricate way: first, he buys Bitcoin in Russia with a Russian credit card, then sends it to his bank account in the UK, which he still maintains, and from there the money goes to a Bunq account in the Netherlands. That means navigating a sea of fees and regulations.

He also got an interest-free loan from the fund set up by the university for Ukrainian, Russian and Belarussian students. He compliments UU for making the process really easy. “Usually, you need lots of documents to get a loan. In my case, it was just four lines: my name, the sum I required, what I was going to do with it, and my IBAN”. He hasn’t touched the money yet. “I took it just in case something happens. Things are so uncertain. But at least now I feel like I’m getting back on my feet.”