Calls to expand the right to award PhD degrees

'All university lecturers with PhD degrees should be professors’

The university's anniversary celebrations (best known as Dies Natalis), which happen on March 27, are always kickstarted by a procession of professors wearing togas. Walking the path from the Utrecht University building to the Dom church is a privilege reserved for active and retired professors. Although it's nice to make the university’s achievements visible, there is something strange about it. Why are professors set apart like this? What makes their work so much better than that of the rest of the employees?

The position of professors has been a hot topic lately. In the Netherlands, only those with the title of hoogleraar are allowed to call themselves professors and thus gain the prestige that comes with it. In addition, a professor has certain privileges that other scientists do not have, such as the right to award PhD degrees and wear a toga at academic ceremonies.

“Only an elite group is allowed to wear a toga,” notes UU professor James Kennedy in a column in the Dutch newspaper Trouw (available in Dutch only, Ed.). Kennedy emigrated from the US to the Netherlands twenty years ago. “I’m not the only foreigner wondering why a country that claims to be egalitarian maintains such a hierarchy. The Netherlands may have a less hierarchical academic culture compared to France or Germany but the toga still seems like an important element to maintain the pecking order.”

Emphasis on teamwork

But the discussion goes further than the garment. Jan Smits, a law professor at Maastricht University initiated the debate with an op-ed titled "Down with the Professor, everyone is a professor", published in the newspaper NRC Handelsblad (Dutch only, Ed.). Smits argues that the current system needs to be overhauled if we are to be serious about "making space for everyone’s talent". He justifies his position by mentioning UU's new Recognition & Reward policy, a pioneering measure. According to this policy, education and research should focus more on teamwork and less on the leader of the team. To Smits, this is reason enough to question the existing hierarchy.

He proposes to abolish the existing ranks and call everyone a professor. In principle, everyone would have the same educational and research tasks, including the possibility to award PhD degrees. Whether a scientist is able to perform these tasks would be assessed on a case-by-case basis. In Smits' opinion, if universities want to attract and retain talent, they must get rid of the hierarchical system scientists are supposed to go through after obtaining their PhD degrees. In this system, they start as assistant professors then get promoted to associate professors and then become professors. The higher the rank, the more scarce the vacancies are. According to Smits, this scheme simply doesn't work: first, each university has its own criteria for promoting its employees — criteria that are often not objective. It's not unusual for promotions to be determined by whether or not the institution has the money to do so, instead of the quality or expertise of the professionals, which leads to frustrations. In addition, the responsibilities attributed to each position are not very distinctive: after all, they all research, teach and carry out management tasks to a greater or lesser extent. Finally, the hierarchy sends the wrong message as it suggests that the quality of research work is determined by rank.

Right to award PhD degrees

Hieke Huistra, a historian of science at the Freudenthal Institute in Utrecht, has recently given a good example of this in her column in the Dutch newspaper Trouw. She wanted to nominate a Bachelor's student for a thesis prize but was not allowed to do so because she is neither a professor nor an associate professor. As the student’s first supervisor, she had to pass on the request.

As a second example, she mentions the right to award a PhD degree. She supervises a PhD student along with a colleague. They both raised the funds for the PhD together and Huistra has all the necessary expertise in the field but, in the end, she was not allowed to judge whether the thesis was good enough. “I had to ask another professor who knows a thing or two about it, sure. But, if I may be so bold, this person knows considerably less than my colleague and I.”

James Kennedy is surprised that the right to award a PhD degree in the Netherlands is reserved for professors and a limited number of associate professors. In the USA, there are three types of scientific appointments: assistant professor, associate professor, and full professor. They all have the right to award PhD degrees.

Belgian system

The same applies to Belgium, where every scientist with a PhD degree who carries out teaching and research assignments is given the title of professor and has the right to award a PhD degree. There are still differences between the positions of lecturer, senior lecturer and full professor, but they are limited. “There is less hierarchy and symbolic distinction within the university and, to the outside world, everyone is a professor,” explains Ingrid Robeyns in the newspaper NRC Handelsblad (Dutch only, Ed.).

As far as she is concerned, the fundamental problem of the Dutch system is that the number of positions awarded the title of professor has been kept low artificially. There are only a limited number of vacancies, which means that many excellent assistant professors and associate professors will never get to become professors. Since professors are highly regarded in society, outstanding assistant professors will never get the recognition they deserve. Professors are usually preferred in debates and committees.

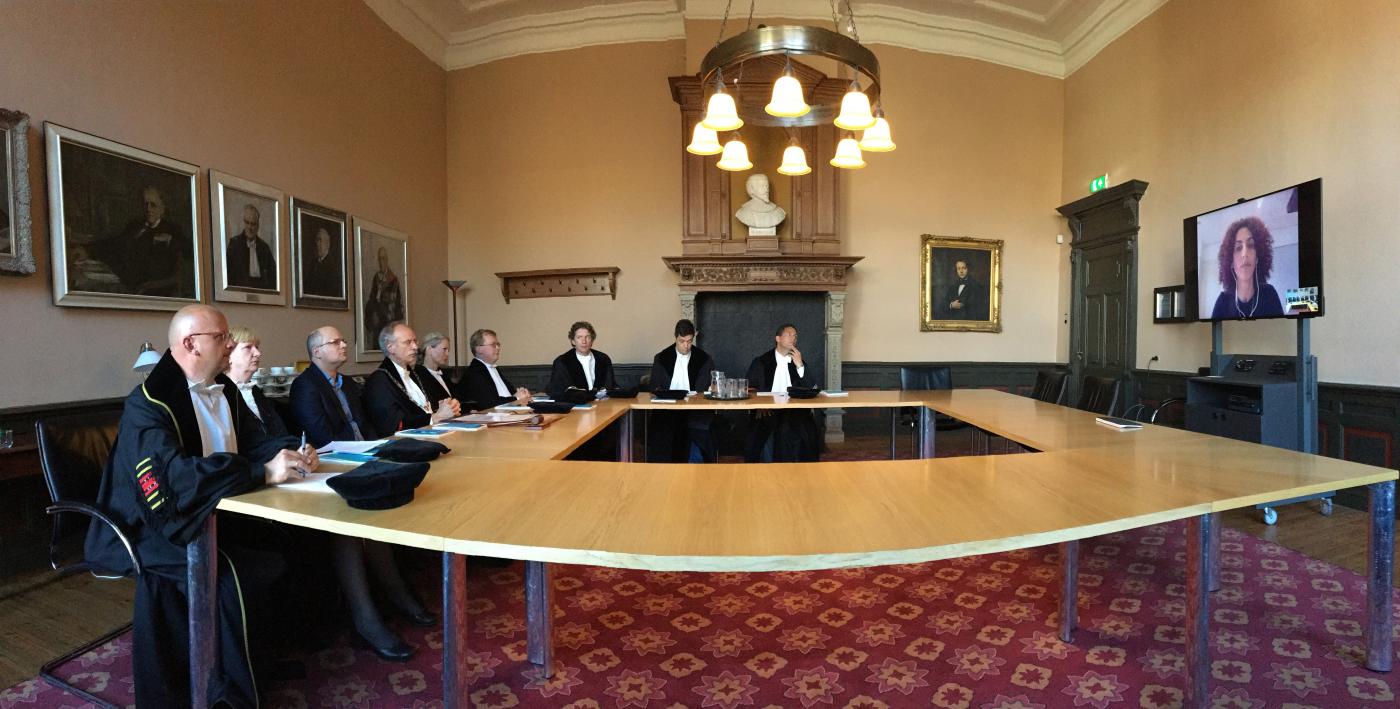

A PhD defence through Skype. Photo: Bas Schreiner

No protected title

As far as rector Henk Kummeling is concerned, everyone can call themselves a professor, as that is not a protected title. However, he is not in favour of giving everyone with a PhD degree the so-called Ius promovendi. “The fact that someone has proven research qualifications does not mean that they are a good supervisor yet. These past few years, we have learned that supervision can be a problematic area, which is why researchers must first be trained to supervise properly before they can be granted the right to award a PhD degree.” The rector notes that this right has already been expanded considerably throughout the years. “More than 150 associate professors at UU have gotten a lus promovendi these past few years, out of a current total of 340.”

Kummeling also disagrees that the toga is a mere garment. “It symbolises academic values. Toga wearers are the carriers of those values as they have proven leadership in matters that are important to us, the most central of which are independence and integrity. If a professor violates these two principles, the toga has to be rescinded. It is not a coincidence that we've been paying more and more attention to these values lately."

Symbolic inequality

Paul Bosselie, professor of Public Administration & Organisation Science and pioneer of the Recognition & Reward programme, also warns against egalitarianism. “Carrying the title of professor is more than a title,” he says. The position requires a certain responsibility and leadership abilities: professors have demonstrable qualities that allow them to feed the social and political debate with scientific knowledge with great authority.”

Bosselie appreciates the fact that associate professors are also able to apply for the right to award PhD degrees. “But even that is not entirely without obligation. Supervising PhD students is not a matter of course and intended promotors and co-promotors must be given the opportunity to learn how to supervise.”

Public engagement activities are often seen as mere hobbies. Photo: Betweter Festival 2016

Support staff

The discussion has expanded to include university employees that are not scientists. At UU, there have been discussions about whether or not the distinction between scientific and support staff should be abolished. Kummeling: “This debate relates to the recognition of everyone’s contribution to the quality of our work: the things we do for education, research, and society.”

In both cases, people always refer back to the Recognition & Rewards system. According to Stefanie Vrancken, a Recognition & Rewards policy officer, by removing the strict distinction between these two types of employees, the Executive Board would be making explicit that their appreciation for employees is universal. She confirms that the existing positions will be kept. “I hope that the gap will narrow and employees will work together more often.”

Social safety

It is clear that Recognition & Rewards has changed the way we think about scientific jobs. Hieke Huistra calls it the academic pyramid, meaning that the hierarchical system is not conducive to job satisfaction or self-esteem, not to mention it can make employees not feel safe at work. It should be noted that this is not limited to scientific staff. Kummeling acknowledges the problem. “Unfortunately, it is true that a perverted hierarchy prevails in some parts of the university, where people act bossy and lord it over others purely based on the number of PhD students and publications they have. We want to get rid of that for a reason. Open Science and the Recognition & Rewards program should be a crucial part of these efforts.”