Dutch Colonial History

Anton de Kom confronts UU community with hell in Suriname

This year, the online Meet & Read sessions, during which participants read a passage of the book and engage in conversation with one another, are being organised together with Anton de Kom University in Paramaribo. DUB attends a session in which participants read the part about Séry, who flees the plantation where she was forced to work in slavery with her baby Patienta. Unfortunately, she gets captured by the Dutch during one of their forest expeditions to hunt the Maroons (descendants of Africans who escaped slavery through flight and lived in their own settlements in the inland of Suriname).

Agnes Andeweg, Associate Professor of Literature at UU and organiser of One Book One Campus, confesses that she finds it hard to read the excerpt. Not an odd remark, considering Séry and Patienta’s story does not end well, as you can imagine. Her baby is snatched from her hands and Séry is tortured to death. All the participants at the Meet & Read session feel sick after hearing this.

Meredith, a student from Paramaribo, says emotionally: ''This really affected me… I could see the mother and her child in front of me. This forces you to empathise and feel. It is something I am missing in our History books. When someone from Suriname tells our history, you can feel it better.”

Bas Schreiner, Department Manager at the Communications and Marketing Office of the Faculty Law, Economics and Governance, also found it hard to put up with this excerpt: “These… These types of excerpts are written in such a piercing way. I had to put the book away for a while because it was too painful to read. This is not a book you read in one go, you simply can’t bear to do so.’’

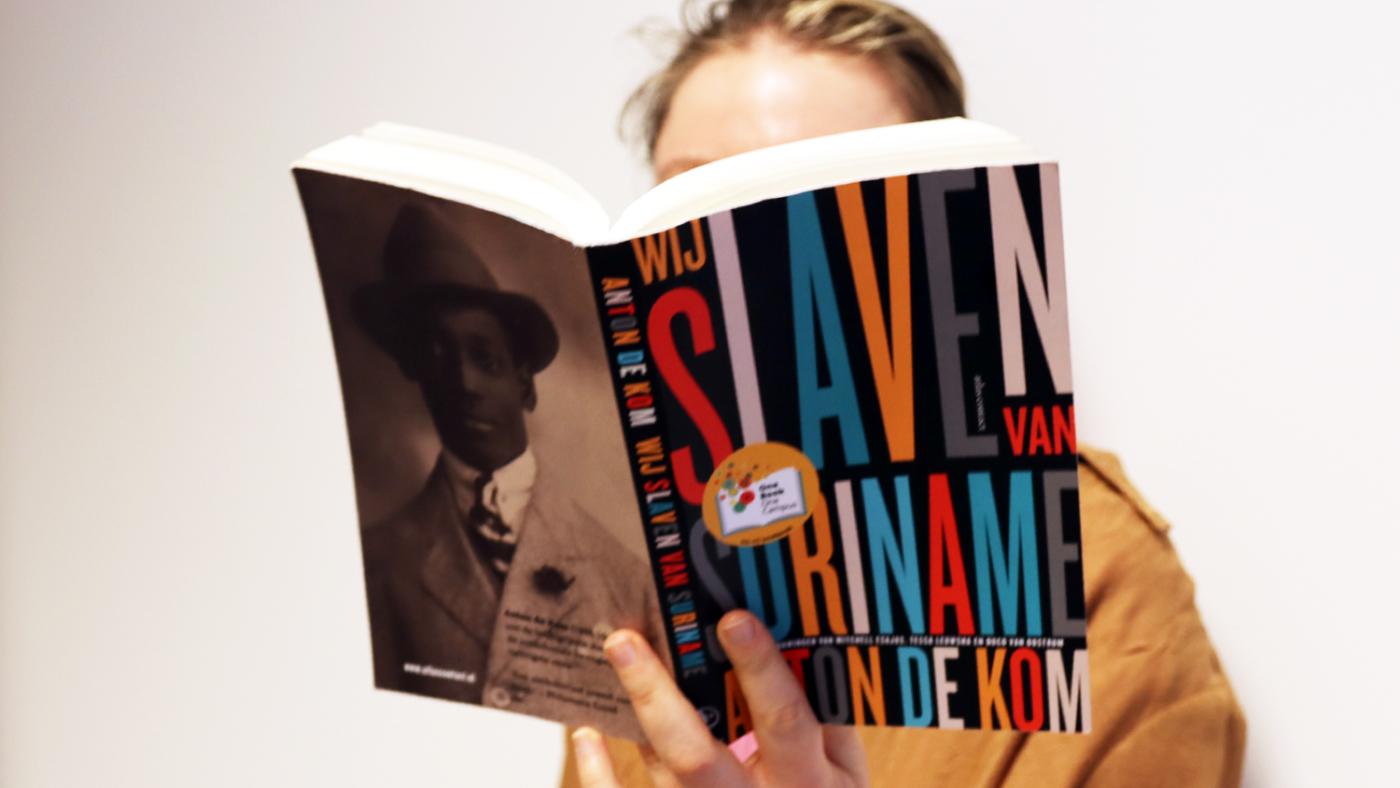

One Book One Campus

One Book One Campus facilitates this type of encounter. Reading together about painful, inspiring, and necessary topics opens up a space for fruitful conversations. This year, however, proves to be a challenge due to the book choice. Not only does De Kom occupy a special place in the shared history of Suriname and the Netherlands, but his book, “We Slaves of Suriname” (1934), is also the first scathing history of Dutch slavery in Suriname from a Surinamese perspective. It is an extraordinary narration of human beings at their best and worst, in which the Dutch do not play the charming part.

Suriname appears to be a breeding ground for Dutch people with a sadistic temper. The excerpts dealing with the horrendous tortures of enslaved people evoke strong feelings of repulsion and make some want to put the book away for good. Reading the book as an organisation proves difficult -- after all, how should one discuss such a fraught history? How do we ensure that people who do not know one another can spend one hour talking about such sensitive topics? What topics should be discussed and which should be excluded from the conversation? And how does one deal with the use of colonial language in the book? When De Kom was alive, usage of the n-word was broadly accepted. Should one read it out loud or not?

During the Meet & Read preparations, Andeweg and her colleagues considered these questions at length. “The violent excerpts hit harder when read aloud. I don’t know if it’s possible to talk about it when the violence is so in your face. As a Dutch person, you want to account for your history, but what do you gain by reading out such explicit scenes of violence?”, says Andeweg, after which she admits: “Since having children I can’t endure much violence.”

Reading the n-word aloud is also tricky. Some session facilitators choose to read the text as originally written by De Kom, while others prefer to emphasise and respect the hurtful impact the n-word can have today, taking a short pause whenever it appears.

Despite all these challenges, Andeweg firmly stands on her decision to propose the entire university read De Kom’s book. “I think everyone in the Netherlands has to read it!”

Personal writing style

The passage on Séry and her baby Patienta is not the only tragedy unfolding in this book. It is full of personal stories that are likely to have a lasting impact on the reader. “His historical writing style was rather unique for the time. He connects factual and analytic historical moments with personal accounts. Basically, Anton de Kom does Human Interest and that’s very special’’, according to Andeweg.

His writing style is effective, based on the multiple Meet & Read sessions in which readers expressed that they felt a connection to the book. One such participant is Marjanne, a student at UU, who says she could understand the gravity and impact of the matter better thanks to the text’s style. “What I’ve learned at school and in History books about slavery was quite abstract. It mentions how the Dutch misbehaved in Suriname, but that’s it, the story stops there. The personal stories in the book are very powerful as they really show you what happened there.”

Personal stories also hit Susan te Pas differently. She is the Dean of University College Utrecht. “He humanises colonial policy. You can see what it brings about in practice. The passage on Séry and Patienta is about the Dutch policy of hunting the Maroons. But what they actually do is terrorising a helpless mother with her child.”

In one of the prefaces of the book, Duco van Oostrum explains that this literary style is in the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance, an Afro-American cultural movement which came about in the 1920s in the United States. It is a broad intellectual, artistic and social movement linked to the rise of prominent African American writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Writer and philosopher Alain LeRoy Lock writes that black writers should describe African-Americans as literary characters, who will then “no longer be a formula but a person” – and that is exactly what De Kom does.

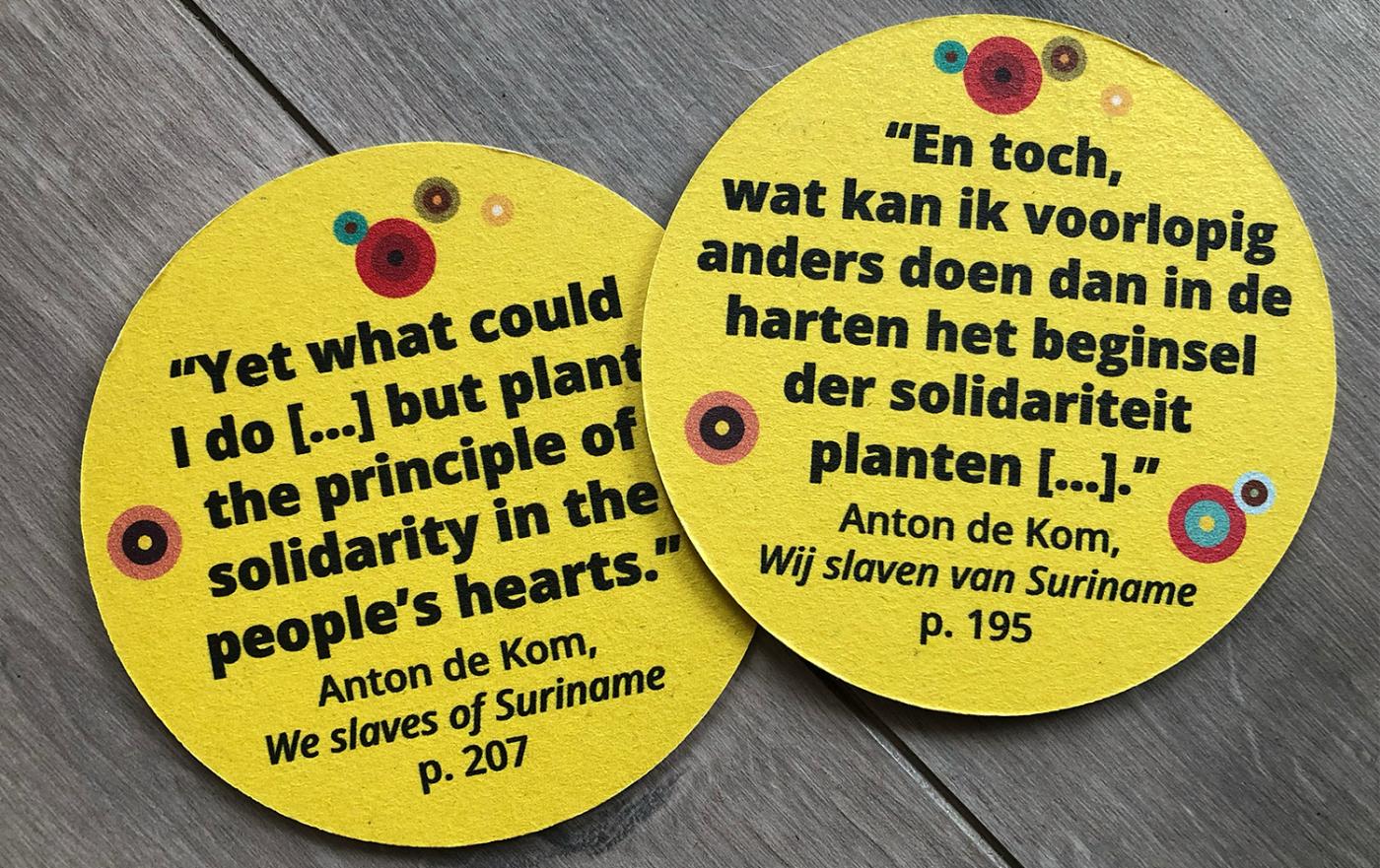

Hope and inspiration

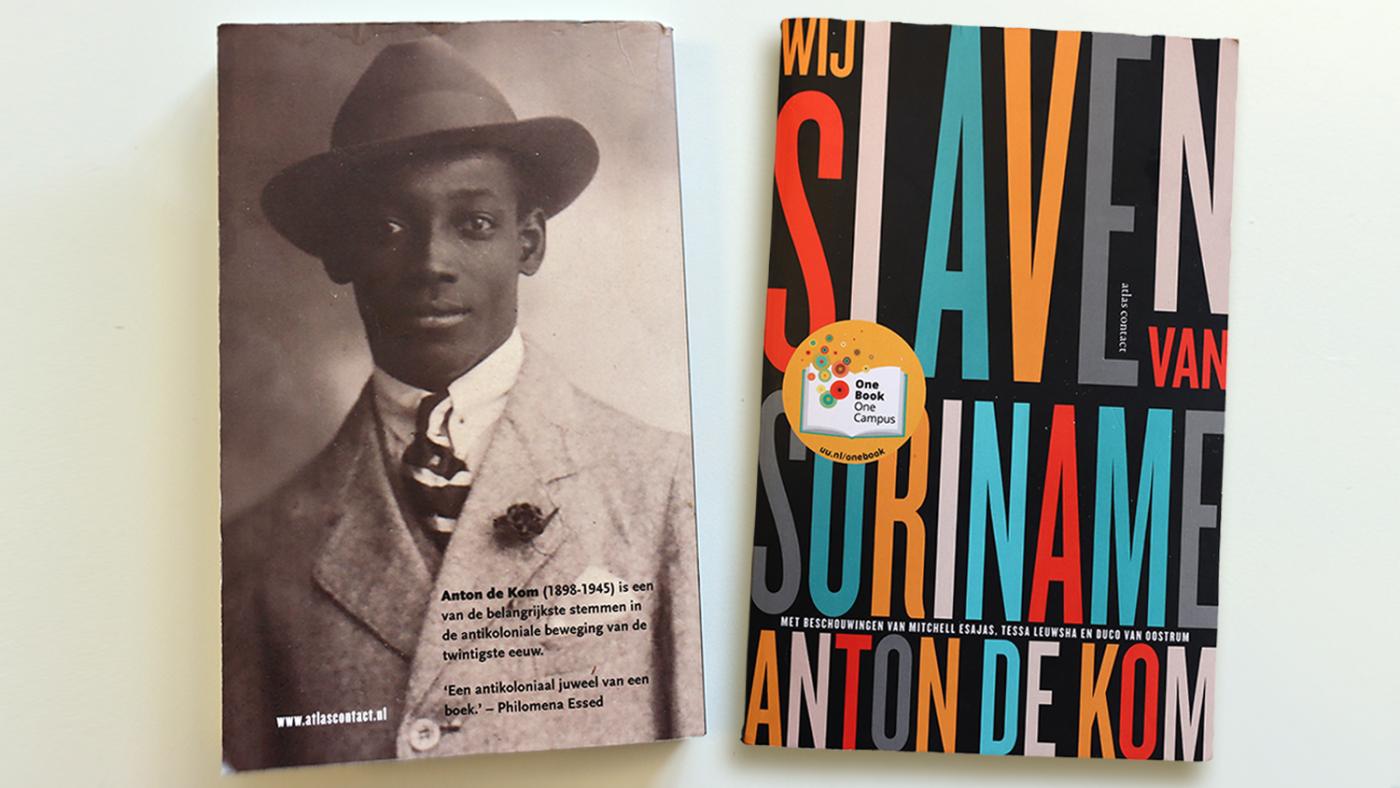

For this reason, “We Slaves of Suriname” is also an inspiring book from which many draw hope, especially readers from Suriname. This also becomes evident in the three reflections that open the book, written by the anthropologist Mitchell Esajas, the writer Tessa Leuwsha and the literary scholar Duco van Oostrum. All three elaborate on the book’s impact and influence. Oostrum writes that De Kom effortlessly carved a place for himself among the most prominent names of the Harlem Renaissance. Esajas places him in the ranks of black intellectuals and freedom fighters such as Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King Jr., Angela Davis, Malcolm X and Frantz Fanon. Leuwsha writes about his life and emphasises that daring to write this book signals De Kom’s courage. In closing, Anton de Kom’s daughter herself, Judith de Kom, writes about her father and his power to bring different communities and cultures together.

Such extensive praise does not come out of thin air as De Kom articulates the first history of Suriname using poetic and erudite language, and portraying the strength of an unbreakable people. Through this book, white Dutch readers get access to a Suriname they barely know. In addition, he also provides an unerring insight into how the aftermath of centuries of slavery lives on to this day. For many Surinamese, this legacy is still palpable in the form of structural inequality and racism.

Impact today

Jonathan, a student from Paramaribo, takes advantage of a Meet & Read session to discuss the impacts of slavery on today’s society. “I wonder what kind of impact this had on people’s emotions and psyche, especially for the Afro-Surinamese.”

Meredith thinks slavery still impacts society a lot: “It used to be fashionable to bleach your skin in Suriname. There is also a social imperative to have children with someone with a lighter skin tone.”

The rest of the participants agree that slavery still impacts the present. Since everyone is on the same page, they start discussing how one could raise awareness of this in society. One of the participants suggests that the book itself should be republished in a modernised version, with more accessible language, as more people might read it then.

Jonathan and Meredith from Suriname let us know that they were happy to join the Meet & Read sessions. Jonathan appreciated that the Dutch students tried to empathise with the experiences of enslaved people. “It shows a level of empathy and awareness which is crucial for understanding the history and impact of slavery on Surinamese society.”

Meredith also found it an engaging exchange.“The interactive sessions were so much fun. I hope they organize more sessions in the future!”

That is not out of the question, as Andeweg is fond of the Meet & Read sessions. ‘These things have to happen more! It is so valuable when people come together and exchange thoughts about subjects they normally don’t talk about. In the end, my reason for organising this project is that I am convinced that the university’s role is guiding people towards independent thinking. Reading something yourself is the very best way.”

One Book One Campus 2024 is a collaboration between UU’s Equality, Diversity & Inclusion (EDI) programme and the steering committee Slavery Past and Colonialism. It is part of Diversity Month and aims to strengthen a mutual sense of community at the university.

Anton de Kom wrote “We Slaves of Suriname” in the Netherlands, after being exiled from his beloved Suriname by the Dutch colonial governors. His political activities and consultancy work, performed from his parents’ house, frightened the Dutch regime because he helped Surinamese workers with their rights. Being exiled did not wane his fight for freedom and against injustice: once in the Netherlands, he continued where he left off in Suriname. During the second world war, he was active in the Dutch resistance against the Nazi oppressors. Unfortunately, he paid for this with his life. He died on April 12, 1945, from tuberculosis in the concentration camp of Neuengamme, in Germany. De Kom was not included in the Dutch Historical Canon until 2020. Three years later, the Dutch government rehabilitated Anton de Kom and formally apologised to his heirs.