How art impacts scientific research

Art helps scientists think outside the box

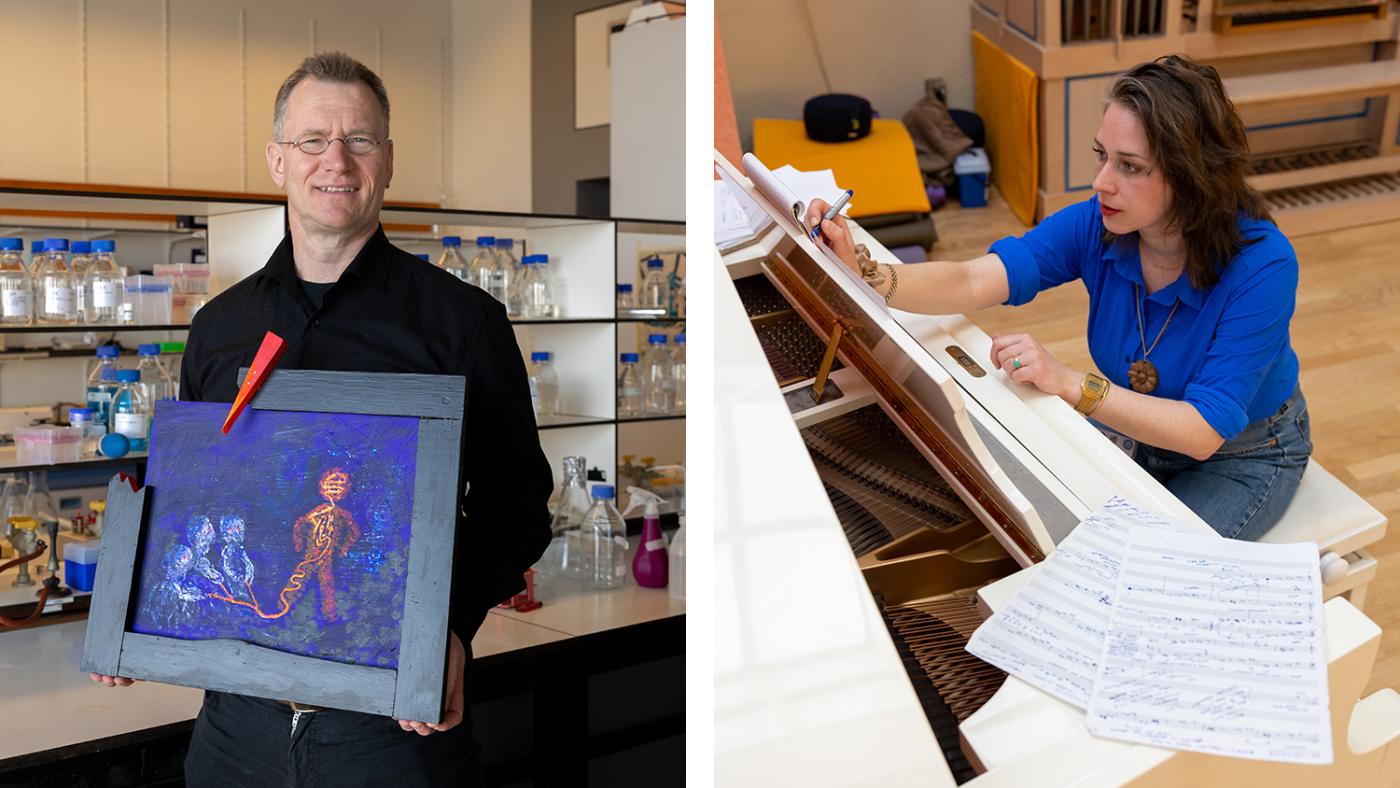

Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, Robbert Dijkgraaf – there are many famous examples of scientists who are also artists. Although at first glance the two crafts seem to differ greatly – objective versus subjective, rational versus emotional – they share many similarities. 'Artists and researchers travel a lonely road in search of innovation. Intuitive ideas and half-baked mistakes are often the starting point of their quest. They create from a place of uncertainty,’ said Groningen's Studium Generale when announcing a lecture by Robbert Dijkgraaf in 2009. Utrecht University also has scientists who use art professionally. The science historian Susanna Bloem, also a philosopher and composer, sees art as a valuable scientific research method, although it often provokes discussion. Stefan Rüdiger, a Chemistry professor and painter, feels that art enables him to depict a complex process, leaving more room for the imagination.

Susanna Bloem: ‘Music creates more space in your mind’

Susanna Bloem has been a PhD candidate at UMC Utrecht, Utrecht University and the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague since 2020. She obtained a Bachelor's degree in History and a Master's degree in History & Philosophy of Science at Utrecht University, all while studying the cello. After graduating, she had several different jobs, including an assistant role in UU's Open Science programme.

‘Many people suffer from time, saying they feel stuck and have no perspective. When I was a History student, I came across a book by four psychiatrists who researched patients' experiences of time in the 1930s. They described that there are more types of time than just clock time. For example, there is world time such as day and night and ebb and flow. We also have experienced time and inner life history. I was an informal carer at the time and noticed that the book's notions of time corresponded more to my own experiences than the help I got from the mental health care sector. So, I started reading more books on the subject and made it the topic of my Master's thesis.’

‘After I graduated with my Master's, I wanted to continue working on patients' experience of time and write a PhD dissertation about it. It occurred to me that I could investigate this subject better with the help of music. I had already processed the difficult content from those books on my piano. It just makes sense to me – time is a much easier theme to capture in music because music exists by the grace of time. My mother is a singer and my grandparents are church musicians. They raised me with the idea that music and art can help people profoundly.'

‘It turned out to be very complicated to organise and finance such an interdisciplinary study for a dissertation – it took years. I am now being supervised by the University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht University and the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague, and I hope to defend my dissertation halfway through this year. We wrote a piece of music with patients from the closed psychiatric wards of UMC. I sat in front of the piano, and patients could choose to help me with the composition. We listened to the chords together and then talked about it. Some of the questions I asked were: 'What do you need to become a self-healing person? What sounds do you need now? What corresponds to your experiences?' My hand went to certain sounds automatically, and the patients reacted to it. Some of them got very emotional because they could relate to the sounds.

‘When we ask patients to look back on their healing process, almost all of them report going from a time in which they felt stuck to one in which they could imagine a future. This process does not happen gradually but rather through turning points. We are investigating whether art can contribute to accelerating that process. Music creates a mental space where people can appeal to their self-healing capacity. We will produce a series of compositions, a method for implementing public participation in scientific research with the help of art, a set of questions for social workers and, of course, a piece of writing: the dissertation.'

‘My research often triggers a discussion about its value for science. Is one even allowed to work with patients, and if so, what role should the scientist play? Are you still a real songwriter? An academic career is pretty much based on publishing articles, but those articles do not always lead to social change or impact. That's why I have chosen to build an academic career with different kinds of products, such as musical compositions, methods for starting conversations with the public, and co-creation with patients. At the same time, I want these products to be scientifically sound to validate the research. We are working on a follow-up in which the story of suffering and passion will take centre stage, and we want to combine that with body-oriented therapy focused on rhythm and movement. I really want my work to be socially relevant, preferably at the intersection of science, healthcare and art, but I get most of my inspiration from interactions with patients.’

Stefan Rüdiger: ‘Creativity is the foundation of science’

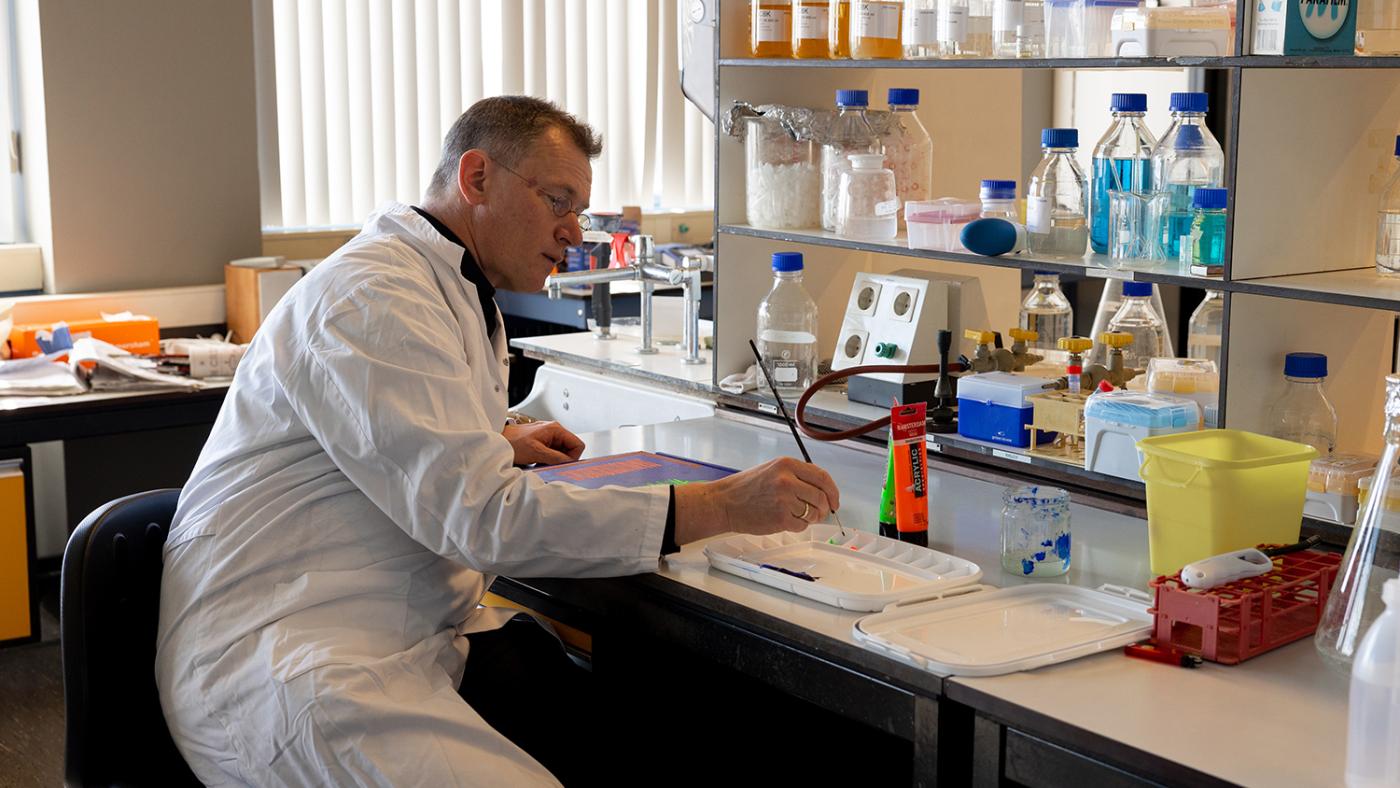

Stefan Rüdiger is a professor of Protein Chemistry of Disease at Utrecht University. He studied Chemistry at Heidelberg University, in Germany, and did his doctoral research at the University of Freiburg. In 2004, after a postdoc in Cambridge, he started a research group in the field of protein chemistry at Utrecht University.

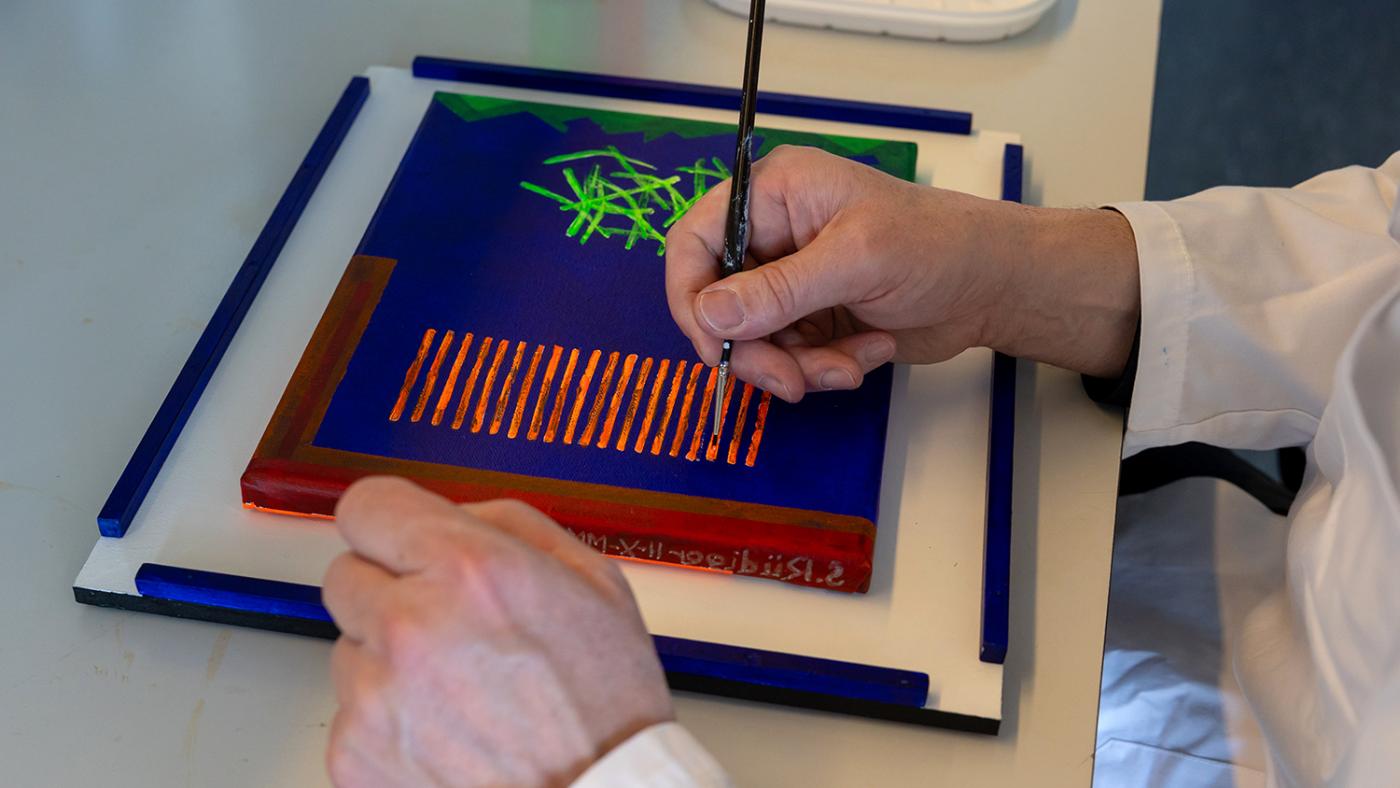

‘The first time I painted ‘science’ was in 2018, when a PhD student of mine was awarded her doctorate. I painted the molecule she had worked on and incorporated some personal features, such as her high heels and red hair. My second painting was on the cover of the renowned magazine Molecular Cell. We had submitted an article about chaperones, a kind of protein machine that plays an important role in protein folding in the body. If this process goes wrong, protein accumulates, which can lead to diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. These chaperones are only active in the first ‘red hot phase’, so I painted the first part of the process bright red. Chaperones only give protein folding a push at the beginning – after that, the process continues on its own. I was surprised that I managed to get on the cover. It is hard enough to get an article published in such a magazine, let alone a cover image.'

‘What leads a person to start painting? I don't know. It's been 25 years since I started painting water and boats. I was born in Hamburg and grew up sailing, which may explain why water and boats were a big theme for me for a long time. I usually paint something for my peers when they have an important event, such as a PhD defence, inaugural lecture or farewell, and that has become a sort of tradition. When I do that, I think about the person and their work and how I can convey that on canvas. I have also made several paintings about chemical processes, which were used in the poster for a conference. I have also had an exhibition at Waterbolk Gallery in Utrecht, and my work will be shown in Regensburg, Germany, later this year. This spring, I will also be participating in I Art My Science, an event organised by Utrecht University, UMC Utrecht, the Graduate School of Life Sciences and De Nieuwe Utrechtse School.'

‘I painted all the visual material for my inaugural lecture in October 2023. There wasn't a single table, graph, or animation to be seen. Protein accumulations are central to the largest painting, but so is ‘fibril paint’, a type of dye that you can use which attaches itself to the protein accumulations. This allows us to recognise the build-up under the microscope. In the future, maybe we will be able to link this dye to a protein that allows the build-up to be broken down. We don't know why people don't get Alzheimer's when they are 30, only when they are older. So, why don't chaperones work anymore when you're older? We hope to gain more insight into this.'

‘My paintings of water and boats wanted to convey a certain atmosphere, but my paintings about science want to express something different. You can depict a very complex process in an abstract form and then decide what you want to emphasise. You can leave more to the imagination, something you can't do with a PowerPoint presentation. Science and art both benefit from creativity. You do something that has never been done before, which is the foundation of science. What makes you come up with an idea that no one else has had before? That doesn't happen by just reading more literature or doing research. You have to read literature, of course, but the more you read, the less creative you become. Creativity is about thinking outside the box and art can help with that.’

A word from this week's guest editor-in-chief, Henk Kummeling:

This week marks the departure of Rector Henk Kummeling, so DUB invited him to be a guest editor-in-chief for a week. He suggested several themes for in-depth articles, and DUB's editors then delved into them. Kummeling explains his reasoning for suggesting an article about science and art:

‘Science and art draw from the same source: imagination and creativity. That is why I have always found the link between art and science to be a very logical one. Time and again, collaborations between art and science lead to an interesting quest and the most surprising and inspiring results. However, art is often much more eloquent than science as it allows us to present science to society in a much more penetrating way. We can encourage our scientists to engage even more with art through our activities in the field of Recognition & Rewards.

In this story, Susanna and Stefan show us how art helps them as scientists and how their scientific work gives them new inspiration for art. As Stefan so beautifully puts it, creativity is about thinking outside the box, and art can help with that. Science can certainly benefit from that too.’