UU's future welcome

Can a robot replace a receptionist?

The new receptionist at the Minnaert Building is called OrionStar GreetingBot Mini. It will be introduced in November as a follow-up experiment to a study into the effectiveness of robots in university buildings without a reception desk.

The project reflects UU's desire to show the world how research and education happening at the Faculty of Science can be integrated into daily business operations. The idea for a robot receptionist came up and Maartje de Graaf, Assistant Professor in Human-Centred Computing, asked Demetra Hadjicosti, a Master's student in Human-Computer Interaction, to conduct a study into the effectiveness of robots in university buildings without a traditional reception desk.

Helpy at work

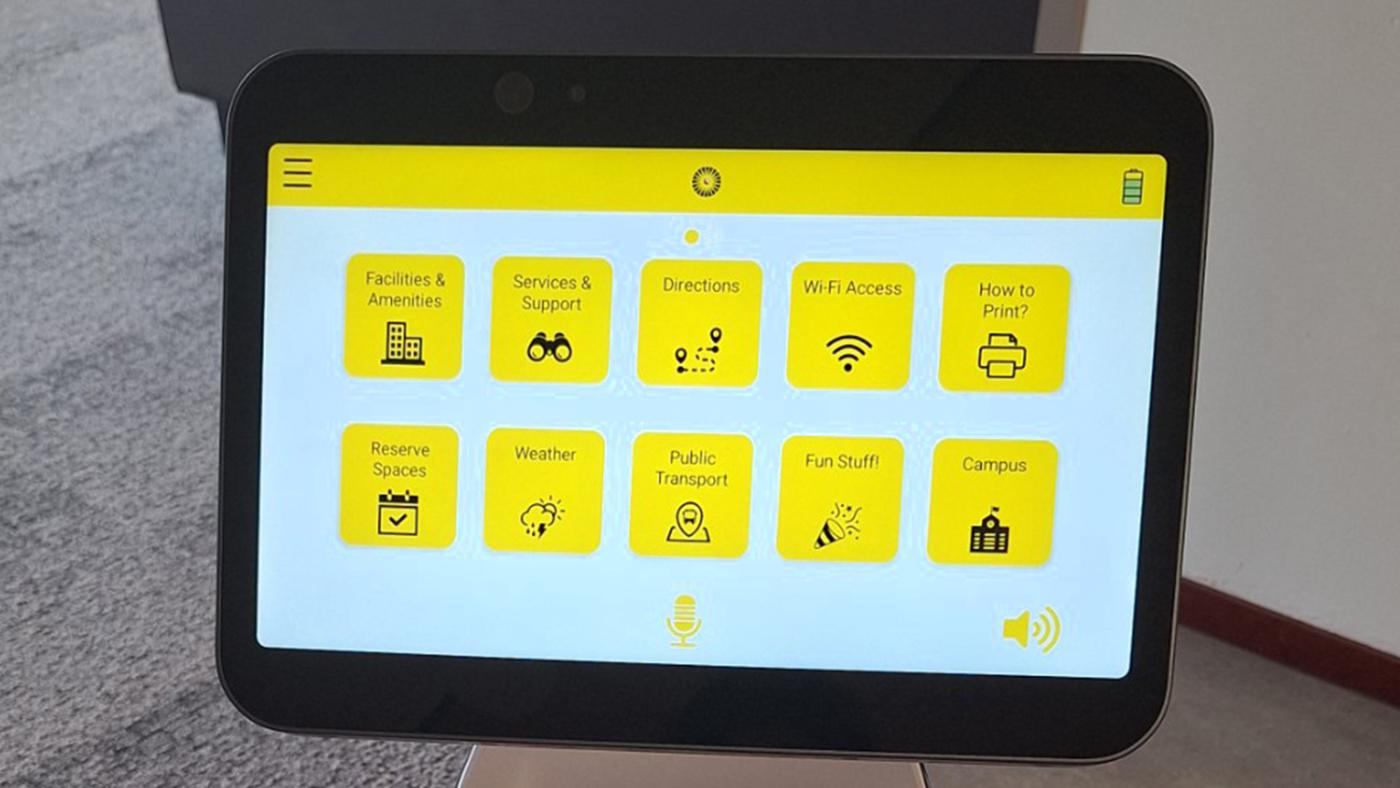

Various receptions were examined in detail for this research. The Master's student spoke with receptionists and visitors to map out their experiences and expectations. What requirements did a robot have to meet? The choice fell on the OrionStar GreetingBot Mini, a hypermodern robot with a friendly "face", also known as Helpy. Equipped with artificial intelligence, this robot welcomes visitors, shows them the way, answers their questions, and occasionally even manages to crack a joke.

The first tests were conducted this year in the Minnaert building at Utrecht Science Park, a building without a reception desk. Helpy then took on the role of host. Visitors rated him with an impressive 84.1 out of 100 on the System Usability Scale. A score above 52 represents a positive user experience. The robot was deemed friendly, helpful and always available.

Extra pair of hands

The widespread use of robots would have many advantages for the university, according to the research. Many buildings lack a reception, which means that visitors often walk around, feeling lost, when they have questions. A robot receptionist like Helpy could be their saviour, writes Demetra.

But Helpy could make a difference even in buildings where receptionists are present, according to an article published by Securitas Nieuws. In this article, Roeland van Oers, Director of Welbo (which stands for Welcome roBOts in your team), spoke with Securitas, the organisation that handles security at UU. He emphasised that it is the collaboration between humans and machines that creates the magic. While a human receptionist can focus on personal contact, the robot takes over the repetitive work, such as showing the way, and is available 24/7. As Van Oers puts it: "The robot does not replace the receptionist, but rather the person at the computer. This gives the receptionist more room to give visitors undivided attention, which only strengthens hospitality."

After Demetra’s research, the Faculty of Science decided to acquire the robot permanently for the price tag of 6,195 euros, excluding VAT. According to Rosa van den Dool, Communications Officer at the Faculty of Science, the success of this test opens up possibilities for broader applications across the university. If people react positively to robots like Helpy, who knows where else we will see them in the future?

Questions about the human element

Helpy will make its official debut as the university’s host in the upcoming open days of the Computing Science programmes, on November 15 and 16. However, the use of a robot raises questions among researchers, ethicists and receptionists, who are wondering how robots like Helpy can be used without compromising human work and personal interaction.

Finding a balance between service, efficiency, and the warmth of a human smile seems like a challenge. Is Helpy a harbinger of a more efficient future or should UU be careful not to lose the human element? Can a robot do more than just smile and point? Visitors expect a good service, can technology deliver that?

Photo: Harold van der Kamp

Shortcomings

According to lecturer De Graaf and Cindy Friedman, PhD candidate in Ethics regarding humanoid robots, there are shortcomings to robot use in receptions, too. While a human receptionist can respond empathetically and read emotions, a robot is simply a machine without feelings. Imagine a visitor panicking because of a medical emergency – a robot could never calm them down or make quick decisions like a human could. It's at moments like these that technology fails, says Friedman.

In addition, robots' performance is not ideal in busy or noisy environments, according to Demetra's research. The robot sometimes had difficulty understanding voice commands, which led to frustration and misunderstandings.

Another ethical dilemma mentioned by De Graaf is privacy. What happens to the data the robot collects? How empathetic can robots be? "Robots can simulate empathy," says De Graaf, "but it remains an illusion and can even be misleading." People may think that the robot genuinely understands and empathises with them, even though it is just following fixed patterns and algorithms.

Accessibility is another factor that should not be overlooked. Not everyone is equally adept with technology and robots must be accessible to all users, including the elderly and people with disabilities. In addition, there must be a clear responsibility structure: who is liable if a robot makes a mistake or causes damage?

Ethicist Friedman adds that technology is not always an improvement. “During the Covid-19 pandemic, I was frustrated when chatbots were the only option to communicate when in stressful situations. The lack of real empathy makes such an experience even more difficult.”

She emphasises that the value of a robot depends greatly on the context. “In a clinic, where people feel vulnerable, human warmth is indispensable. There, a robot feels like a cold, dystopian solution. In an innovative setting, however, such as a university or library, a robot can work well.”

Photo: Harold van der Kamp

New colleagues?

According to Communications Officer Rosa van den Dool, the future of robots like Helpy at Utrecht University is still open. Although a new test will soon take place in the Hans Freudenthal building, which currently has no receptionist, there are no plans to expand the use of robots at the moment.

These tests are mainly intended to investigate how the robot functions in different situations, such as open days and other meetings. As for ethics and privacy, Van den Dool emphasises that precautions have been taken: the robot does not recognise faces and does not collect personal data.

Nevertheless, lecturer De Graaf warns that more research is needed to understand how people respond to robots in day-to-day life. The process of acceptance takes time and requires long-term studies. According to her, the future lies in hybrid systems, where visitors have the choice to turn to a robot or a human. This way, robots can take over routine tasks, while people focus on empathy and more complex issues.

Niyazi Sert when he said goodbye to the reception of the Faculty of Pharmacy after years of service. Photo: DUB

Folder full of thank you cards

Niyazi Sert has been working as a receptionist at the university since 2001. Although he sees how robots could offer an advantage, such as making buildings without receptionists more accessible, he remains sceptical. “A robot could never replace face-to-face contact,” he says. While I speak with him, several colleagues drop by for a chat. That happens often, a sign of the bond he has built with the people around him over the years. Campus columnist Monica van de Ridder wrote earlier this year that she feels welcome in the Langeveld building because of Sert.

“You know what?” Sert says, laughing, “You should ask the employees what they think of that robot receptionist. With me, you'll only get advertising pitches so that I can keep my job!” He winks and then shows me a folder full of thank you cards he has received from visitors over the years. He has been saving them proudly and plans to do so until his retirement. “These are the little things you can’t replace,” he explains. “People appreciate that connection and that’s exactly what a robot could never provide. It’s not just about the information you give, but about the feeling that you see someone, understand them, and care.”

Sert also shows me a pinboard behind his desk, full of photos of student boards he’s gotten to know over the years. “I want to recognise everyone who comes here,” he says. “That’s what makes my job special. It’s human work and that’s the best part.” For Sert, the job is about real connections, something a robot can’t replicate.

As I walk away, he reminds me not to forget my jacket—a small gesture, but one that a robot would probably miss.