Sodomite persecutions in medieval Utrecht

The rainbow community in a new light

An inconspicuous plaque can be found near the entrance to the Utrecht University Building, on Dom Square. It carried the inscription 18th century - Sodomy - Barend Blomsaet and 17 other men were convicted and strangled in Utrecht. Their deeds hushed up. The memorial refers to a dark page in the history of the city.

On 11 January 1730, 44-year-old Josua Wilts, a guard (sexton) of the Dom Tower, filed a statement that would mark the next two years, according to court records in the Utrecht archives. Wilts claimed that he had seen two men, Louis and Gillis, having sex in a chapel in the Dom Tower. This was a serious accusation as sodomy – how homosexual acts used to be called – was punishable by death. Wilts had caught the men by chance when he and his sons looked down through a hatch from his upstairs house.

During the extensive investigation that followed, one of the accused, Gillis van Baden, admitted that he had performed sexual acts with several men in the chapel. One of the accomplices could be traced and he, too, subsequently mentioned names of sexual partners.

The plaque on Dom Square. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Prison sentence

A key figure in the investigation was a man named Zacharias Wilsma. The court heard him six weeks after the first sodomy charge, on 22 February. He mentioned the names of dozens of accomplices across the country, causing the witch-hunt for sodomites to spread like wildfire through the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Ed. Predecessor state of present-day Netherlands).

Wilsma would remain imprisoned until his death. Whereas only a handful of sodomy trials had taken place in the previous century, the sudden wave of persecution from 1730-1732 led to almost a hundred death sentences, of which at least thirteen took place in Utrecht. Many other accused men fled the country or received milder punishments, such as banishment or imprisonment.

Abominable sin

The sodomite persecutions were the talk of the day in the Republic. Pamphlets, poems, and moralising texts sprang up like mushrooms. For instance, the journal Europische Mercurius published a full issue with a sodomy theme. According to historians such as Randolph Trumbach and Noël Malcolm this was a big change because before 1730 this sin was mentioned as little as possible, and if it was written about at all, it was in veiled terms. Crimen nefandum, or "a crime one should not speak of" was a common way of referring to sodomy. Talking about sodomy could give people ideas. The sodomite prosecutions testified to a new philosophy in which deterrence was central.

In the 1730s, people in the Republic thought that sodomy was a relatively new phenomenon in the country. An anonymous author wrote, for example, that "Sodomite abominations [....] were sufficiently unknown to the greater part of the inhabitants of our country by far.” The reason for the sudden increase in this "abominable sin" was thought to include foreigners, immigrants, and overseas trade contacts. Diplomats who came to the Republic during the negotiations for the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), for instance, were said to have brought sodomy with them and 'inflamed' the pious, virtuous Dutch. Catholics, Italians, Spaniards, and French in particular, were said to be very adept at sodomy.

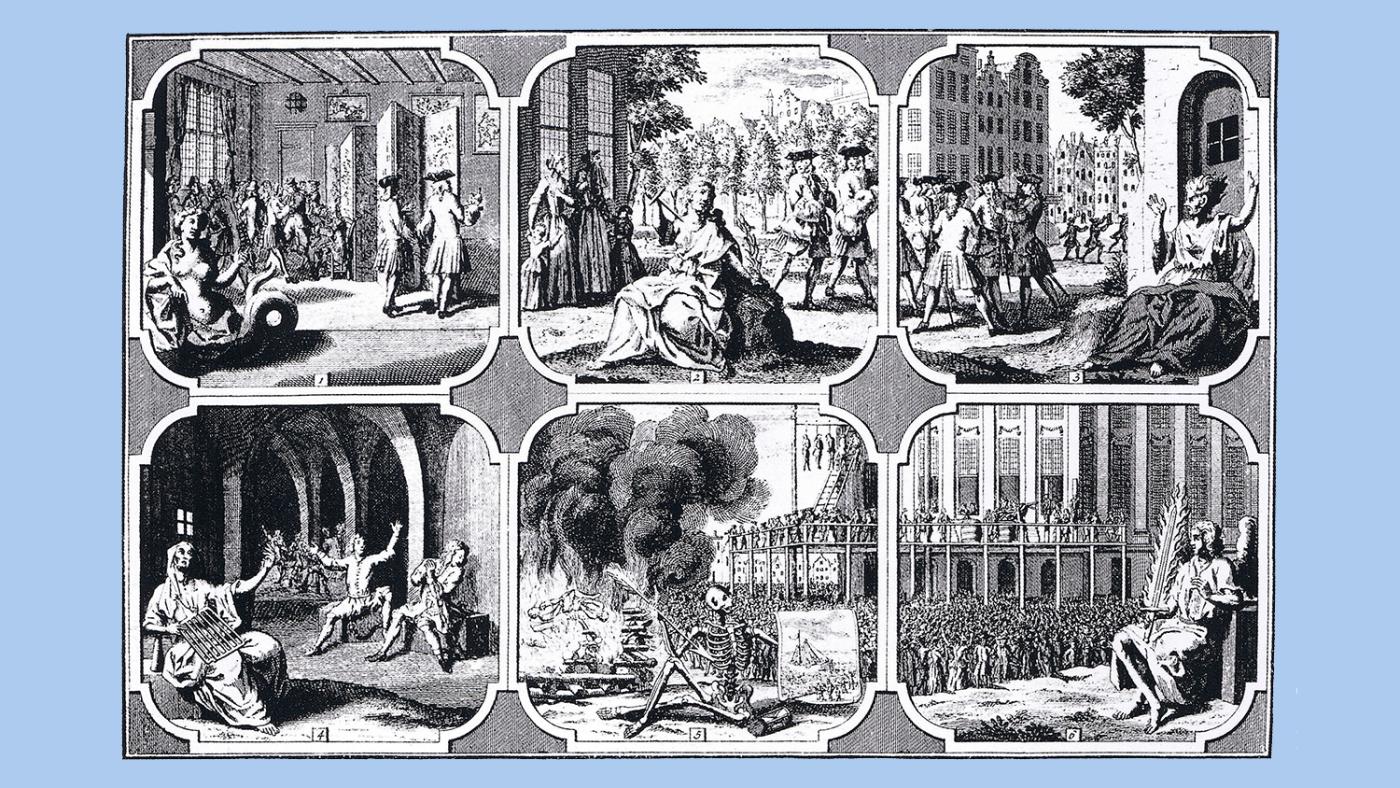

Pictures about the persecution. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Copy/Paste

In countries where homosexuality is not tolerated today, people seem to have simply copy-pasted the thinking of three centuries ago. Russian anti-gay propaganda legislation, for example, doesn’t refer directly to homosexuality, but to "non-traditional sexual relations." By using this terminology, Russia implies that homosexuality (and the rainbow community) is a new phenomenon that doesn’t belong to traditional Russia. It’s also not hard to guess what Putin believes would have exported homosexuality to Russia: the West. Moreover, by talking about "non-traditional sexual relations", Russia is doing he same as the authors who called sodomy the "crime one should not speak of ". Russia seems to be hoping that the rainbow community will disappear by not calling the beast by its name.

According to Russian rhetoric, homosexuality stems from the typically Western trait of decadence. This same thinking can be traced back three hundred years ago, but then decadence was mainly associated with Italians, according to several pamphlets and poems from that period. Sodomy was said to stem from an inability to control carnal lust and this fitted well with the existing stereotype of Italy's Catholic inhabitants. The Republic was predominantly Calvinist, so there was plenty of reason to paint a hostile picture of this dissenting country. The Italians performed the same function three hundred years ago as the West does today for Russia: the scapegoat of sodomy. This us-versus-them thinking at the expense of sodomites and gays has a function; it contributes to the formation of an identity.

The Netherlands

Not only among countries with explicitly homophobic governments can similarities with 18th-century perceptions of sodomy be found, but also in the Netherlands. For years, for instance, the leader of the right-wing party PVV, Geert Wilders, has been agitating against the "woke dictatorship" that would indoctrinate children with ideas about the rainbow community. The outline agreement of the new Dutch government states that sex education should be "neutral". So, Wilders too seems to be employing the "unspeakable crime tactic", assuming that children are more likely to join the rainbow community if they are exposed to the ideas.

In addition, there are increasing calls to abolish "identity politics". By this, parties like Forum for Democracy and JA21 refer to "The idea that politicians should start favouring specific groups of people [...] because they supposedly possess a certain ethnic, sexual, cultural or religious 'identity'," according to Forum's website. The political party, led by Thierry Baudet, favours banning rainbow flags on government buildings and banning children from pride parades.

Opponents of identity politics thus advocate a form of homosexuality that is close to sodomy. Gay people are tolerated, as long as they do not express their sexuality as part of their identity. As with sodomy, the emphasis is on homosexual acts rather than a homosexual identity.

Canal Pride Utrecht. Photo: DUB

These days, queer couples walk across Dom Square every day, probably unaware of the city's bloody past. Modern day Utrecht has transformed into a champion of queer rights. It organises the annual Queer Film Festival, hundreds of students cycle along the rainbow bike path on the Utrecht Science Park and a pride flag flies on the Academy building during National Coming Out Day. Sexual diversity is no longer a sin, but something to celebrate. After the dark chapter of 1730, comes a rainbow-coloured one. The monument at the Dom Square recalls that only too well.

Rainbow flag at Utrecht Science Park. Photo: DUB

Rainbow flag

Tomorrow, Friday October 11, at 9:00 am, the rainbow flag will be raised at both the Utrecht University Building in the city centre and the Administration Building at Utrecht Science Park. At the Academy Building, this will be done by representatives of the Anteros student association and the Queer@UU network. Diversity Dean John de Wit will say a few words and also discuss the history of Domplein and homosexuality. Members of the Queer@UU network will be present at the flag-raising at USP.