In search of a better society

‘Scientists should act like critical friends’

Are researchers fact checkers, interested in pure data, or do they want to set a social movement in motion? At the conference Making a Difference: Societal Impact through Collaborative Research, UU's brand-new rector Wilco Hazeleger said that connecting with the world around them is a big challenge.

The rector opened the two-day meeting of the Utrecht Data School, which brought together scientists from all over the world, people working at universities and universities of applied sciences, and employees of various companies and public organisations. On Monday and Tuesday, the event discussed how academia can contribute to a better society in tangible terms.

‘Our university is not separate from society,’ Hazeleger told the audience. ’We are part of it, which makes it difficult for scientists to determine their position. After all, you want to show the results of your research and have an impact.’

Initiator Mirko Schäfer from the Utrecht Data School appreciates that scientists are getting involved in social debates. ‘Scientists are often seen as “fact checkers”, but that is not enough for me. We can play a more visible role when tackling problems. After all, collaboration allows us to gain a better understanding of the problems of our time.’

Science produces knowledge, but what to do with it? Should academia pass that knowledge on to administrators and politicians and let them decide what to do with it, or should scientists be more active?

When it comes to climate research, more and more scientists are taking a stand. They are warning society of the consequences of not taking drastic measures to fight climate change. They are also proposing tangible measures and sometimes even engaging in activism. Part of society sees these academics as ‘naggers who are imposing their opinion’.

Mirko Schäfer wants science to play a more visible role in society. Photo: DUB

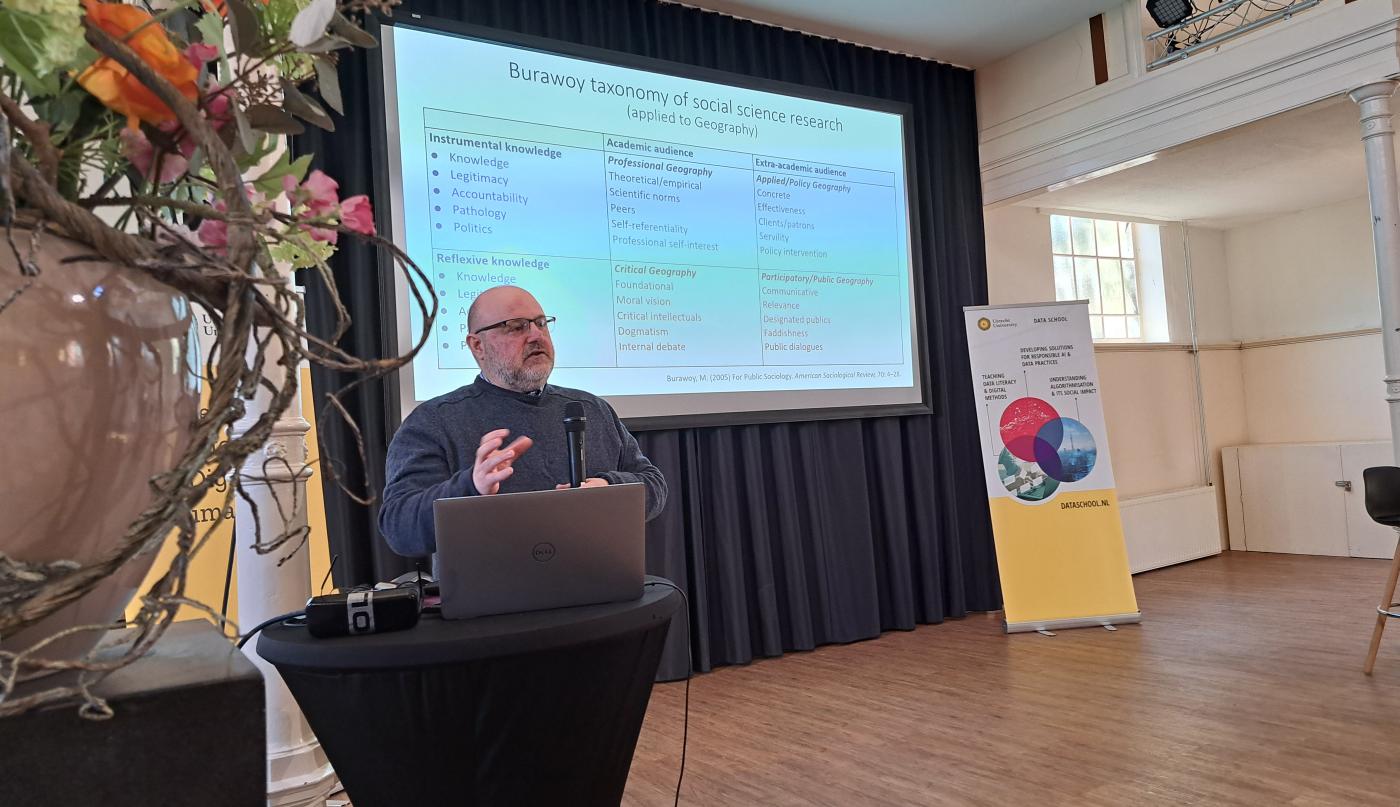

‘The idea that a scientist is politically neutral and independent is long outdated,’ says Irish geographer Rob Kitchin, the conference's first guest speaker. ’As a scientist, you must show where you stand and how you got there. That is transparency. You cannot claim your research is the only truth.’

Kitchin distinguishes between different types of research and different types of attitudes scientists display. Some academic works go for instrumental knowledge – publications mainly aimed at their peers and scientific journals. Others, however, produce reflective knowledge, which is more applicable to society. For this type of scientist, attitude is of utmost importance.

Which of these profiles is the most impactful: the independent researcher who limits themselves to providing the facts or the activist who, based on the research, has a clear picture of what needs to change? Kitchin prefers a third variant: the researcher who acts as the ‘critical friend’.

A critical friend is someone who participates in the project, listens carefully to the organisation's wishes and, based on his research and expertise, asks critical questions to keep the project on the right track. He is a participant and tries to have an impact from within.

Rob Kitchin during his lecture at the Impact conference. Photo: DUB

As an example, Kitchin mentions a large project in Dublin in which the city collects as much data as possible about housing, from luxury homes to homeless people's whereabouts. ‘How do you do that responsibly, and what conclusions can you draw from the available data? We strive for an ideal world, and data can help us take steps in that direction.’

Kitchin's main message: ‘Make sure you are present. You need to be in the room.” That's how you know what is going on, and you can influence it. If you actively collaborate with other organisations, you can build a network that will benefit you later. This requires patience, a willingness to accept compromises and waiting for the right moment to present your critical information.’

The audience asked whether researchers could work with each other at all from that perspective. Consider, for example, the fossil fuel industry, which often partners up with scientists to give people the impression that they are willing to change, but don't care much about it behind the scenes. This practice is best known as greenwashing.

Kitchin agreed that this can be a problem. ‘As a scientist, you will always have to weigh up the pros and cons. And sometimes you may decide not to cooperate if you feel your contribution will not have a positive effect on a better society.’