Spinoza winner: ‘You can collaborate and yet stay visible’

No, she’s fine at the fifth floor of the Kruyt building, really. The concrete colossus has been on the to-be-demolished list for years, and is constantly being patched up just enough to stay upright for a few more years, but you won’t hear Anna Akhmanova complaining. “It might not be the most beautiful building, but it’s fine on the inside.”

And now, starting this week, it’s also a building that houses no less than three Spinoza winners. Last year, Albert Heck received the highest Dutch distinction, as had Piet Gros before him. Both top scientists in chemistry are about to move to the De Wied building, just like other chemistry groups. And that’s something that saddens youngest Spinoza winner Akhmanova. “There are amazing chemists here with whom I love collaborating. At least, fortunately, they’re all staying here on campus.”

My wishes have, for the largest part, come true

The focus on collegiality is a recurring theme in the interview with the cheerful scientist. In a fast-paced flow of words in which each word is falling over the next, she repeatedly praises the qualities of the research groups in her vicinity, as well as those of other UU and UMCU scientists and researchers at the Hubrecht Institute.

When she came over to the UU from Rotterdam seven years ago with colleague Casper Hoogenraad, she’d chosen Utrecht mostly for its large array of life sciences groups. After the air had been cleared from the metaphorical explosion their recruiting had caused (the dean had hired the two unbeknownst to the faculty council, in the midst of a massive reorganisation), the Russian scientist made sure to make full use of this, too.

“I’d most love to cover the entire spectrum: from research on the structure of a molecule, to tumour experiments with patient material. As there are so many different research groups here, as well as an academic hospital, it’s possible to do that here. My wishes of seven years ago have, for the largest part, come true.”

You have to know exactly how processes in the body work

Akhmanova has proven herself in Utrecht to be the world’s most prominent expert in cytoskeletons. The cytoskeleton is the framework of filaments and tubules that gives a cell shape and stability, and is responsible for intracellular transport. “It’s fundamental research,” she explains, “but there are noteworthy clues that point at the possibility of using this type of research for new treatments for diseases.”

She mentions the medication Taxol, which is already being used in the treatment of ovarian cancer and breast cancer. The medication focuses on disturbing the production of microtubules and with it inhibiting cell division. Akhmanova, along with UMC researchers and Delft-based colleague and fellow Spinoza winner Marileen Dogterom, recently showed that cancer metastasis can possibly be inhibited in the same manner. “Chemotherapy often damages all cells, which is why everyone’s looking for very specific treatments. To do that, you need to know exactly how all processes in the body work.”

But her research can also be relevant in neurological defects. Akhmanova discovered the role the cytoskeleton plays in the formation of the neurological eye disease CFEOM1, in which the pupils are directed downward. It’s possible research like this could help in, for instance, battling ALS. “Cancer is more and more treatable, whereas there isn’t a solution yet for these types of nerve diseases. Even the most basic understanding could be a starting point.”

Her Delft-based colleague Marileen Dogterom also received a Spinoza award on Friday. Akhmanova sees this as important appreciation for interdisciplinary collaboration in science. They had earlier been awarded a European Synergy grant for their work together. “Hopefully, this’ll act as a strong signal to young researchers especially: you can collaborate and yet keep your own identity. Because that’s often the problem: people want to work on a project together, but they’re afraid it diminishes their own input.”

The value of the connection to physicist Dogterom is great, Akhmanova says. “We look at things from two different sides, and profit from a difference in techniques, a difference in thinking. Physicists look at models in a mathematical way, and biologists tend to observe more.”

She’s always worked on a varied group of experiments herself. Starting from so-called archaea bacteria during her Master’s in Moscow to fruit flies during her PhD in Nijmegen and micro-organisms in animal intestines during her first Postdoc-period in Rotterdam, her interest eventually shifted to microtubules. “I still profit every day from all those different experiences and insights. Perhaps you’re able to get quicker results if you focus entirely on one thing, but it’s good to keep your eyes open and look around, especially for young scientists.”

I left Russia, and gained the Netherlands instead

Having grown up in an academic family (her grandmother in the field of literature, and both her parents in physics), she left Russia for the Netherlands in 1989, together with her daughter. In the awful Russian economy, the financial situations of universities was miserable. The first step was an exchange at the University of Twente, followed by a PhD in Nijmegen. “I was absolutely set on doing research and making a career out of that.”

After her promotion, an unpleasant time followed, in which Akhmanova found herself without a contract, and, despite being married to a Dutch man, was threatened with deportation. She dismisses that time easily now. “It wasn’t fun, to be confronted with the rules of a system that way, but thankfully it was over quickly.”

She’s mostly been very lucky in her career, she says. “I left Russia, and gained the Netherlands. In Nijmegen, I immediately started speaking Dutch to everyone. I felt very comfortable, very quickly, and that’s never changed."

Healthy competition is also encouraging

When asked about the tough competitive atmosphere in academia, she says: “I don’t think in terms of winners and losers.” She’d much rather see her discipline as a community of like-minded people. Almost all her friends and acquaintances are academics; she travels almost exclusively for research. “Science is a way of life I like very much.”

“I’ve always focused on the topics I found interesting, not the topics that brought me closest to publications in Nature,” she continues. That doesn’t mean there’s never any pressure – but she likes that. “If a grant or paper is rejected, I’m sad first, then angry, and then I’ll start to think. And that process often leads to good things. Healthy competition can also be very encouraging. Only recently I found myself working hard with Marileen to counter a magazine’s criticism. If that improves your results, that’s very satisfying.”

You were always ‘that girl’

Akhmanova is happy with the increased support for female scientists in the last few years. “When I just started, a woman would always be ‘that girl’. That culture, thankfully, has changed now.”

She doesn’t want to call herself a role model, although she’s aware of how much it helps tudents and PhD candidates to see a woman as professor. And she takes her role as supervisor extremely seriously. “I often talk to my team members about which steps they could take for their careers.”

But she’s also worried. She hears many talented, young researchers voice their doubts about pursuing academic careers. They see the tough battle for research funds, the uncertainty that comes with it, and the colleagues who fall by the wayside. “They don’t want to take the risk. And that doubt isn’t entirely unjustified.”

The professor also sees how policy makers’ demands for quick results increase, and with it, the quick redelegation of budgets. She points at the Top sectors policy, in which the collaborations between science and business were praised. “Of course public-private collaborations are great, but you need to check whether there’s actually a basis for it, or if it’s just something that’s being demanded from above. Additionally, research that’s proven its value shouldn’t suddenly end up without any funds.”

We need to realise our science is great, but also vulnerable

Science is a slowly growing tree, they often say. You can’t just chop away at the roots. “In the Netherlands, we have great science. With relatively small budgets, we’re performing at global levels. Out students are wanted everywhere as interns and PhDs. But we need to realise that this fertile climate with this strong tradition, is also vulnerable.”

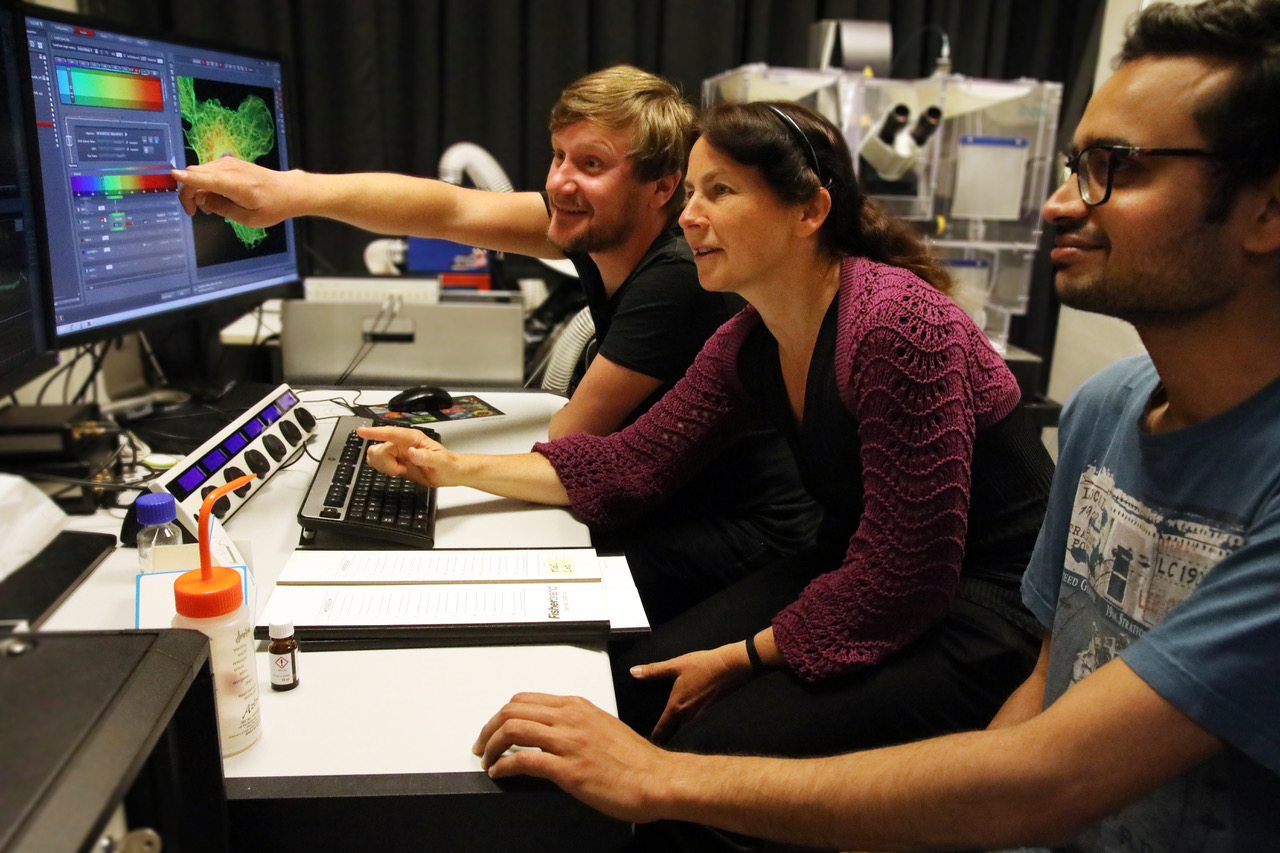

The 2.5 million euros she’ll be able to spend thanks to the Spinoza award will probably be spent on new equipment to strengthen the Biology Imaging Centre. In that centre, which she’s been building with Hoogenraad for the past seven years, she’s trying to bring together high-quality microscopes and the knowledge of the way they work. To answer important research questions, for one, but also to let other research groups benefit from that knowledge.

Akhmanova’s ultimate ambition is outlined in a vision for the future, Bioscopy (pdf), which she wrote with dozens of colleagues: eventually, they’d like to be able to look inside a living cell, in order to see all its mechanisms live in action. “That’s not an original thought of mine, but something that all of us have been working on together.”