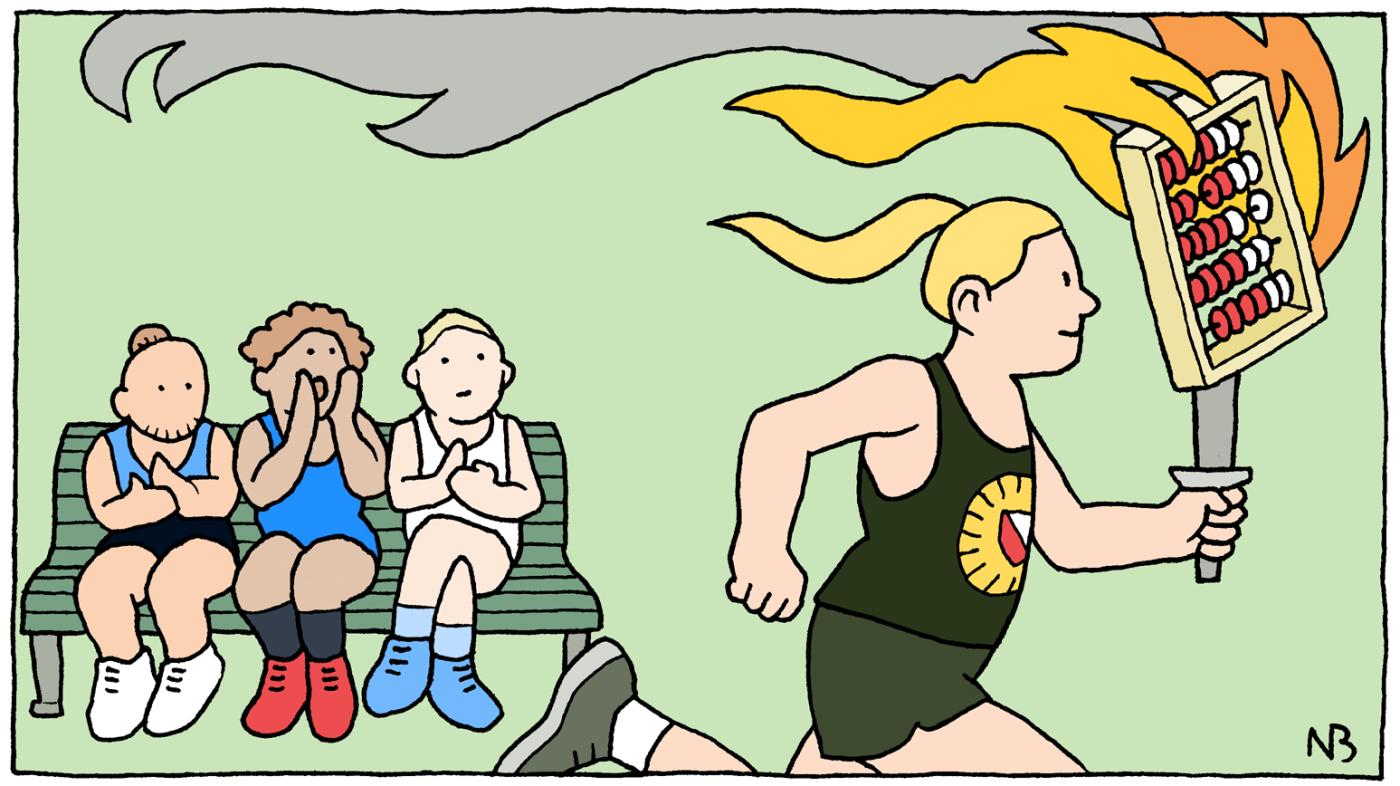

Frontrunner's dilemma

UU is no longer in the rankings. What does that mean?

Sometime in the spring of 2023, UU decided to no longer provide data for international rankings that are not compatible with the university's strategic plan and the concept of ‘Open Science’. This meant putting an end to the collaboration with the well-known Times Higher Education and QS rankings.

It was a remarkable decision. After all, UU had spent years patting itself on the back for its high position in those rankings. In the THE ranking, for example, the university often came in the 60th place, as one of the best Dutch universities. Later that year, UU suddenly disappeared from that list, which caused quite a stir.

But not in the university itself. Due to a mistake, the communications and marketing department had not been informed of the decision made six months earlier and was overwhelmed with questions from the media, students and staff.

The same applied to the internationalisation department, which had to deal with the Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND). IND only issued temporary residence permits to highly skilled migrants if they had studied in one of the top 200 universities in those rankings. This was a potential problem for international alumni who wanted to start a career in the Netherlands. International students also complained to DUB that they were afraid the UU diploma would be less valued abroad too.

Though it made the university look somewhat lousy, the issues were quickly smoothed over as the university was adamant about its decision. It was a very conscious choice and they already had an ally in the University of Zurich.

UU believes that these rankings foster competition too much, which does not go hand in hand with the university's emphasis on Open Science and new ways to recognise and reward its academic staff, two initiatives that underscore the importance of cooperation. In addition, UU wonders whether these rankings can capture all facets of a university.

Speaking to World University News, Henk Kummeling acknowledged that leaving the rankings could risk UU's reputation, "but people choose to study, work or collaborate with UU based on content and quality, not because of its position on a ranking." According to Kummeling, the strategic choice to say goodbye to the rankings made UU "a university with a head and a heart".

The pioneering position

Two years later, Professor Paul Boselie, Chief of Open Science at UU, still fully supports the decision. "Not only because such a ranking does correspond to our strategy, but also because participating costs a lot of money: an estimated 70,000 to 150,000 euros for the entire process."

According to him, THE is ‘a very poor ranking’ that does not measure universities' actual performances. The same goes for the QS ranking in which the UU still appears despite its withdrawal.

‘Surely a respectable university would not want to participate in a ranking with a demonstrably poor methodology, which is in the hands of a commercial organisation that does not operate transparently? I would say: Practice what you preach.’

According to Boselie, UU's pioneering decision has generated a lot of free publicity. Institutions from all over the world invite UU to explain its choice and the philosophy behind it. ‘People admire us for the step we have taken.’

More than a ranking

As it turns out, UU is by no means alone in considering the adverse effects of these rankings. Shortly before the summer of 2023, a committee from the association of Dutch universities (UNL) stated in a report that rankings provide the wrong incentives.

Several similar initiatives have taken place in the international arena as well, such as More Than Our Rank. By displaying that logo on their website, universities show that they excel in areas that are not measured or are poorly measured by the best known rankings.

The Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA), a partnership involving universities focused on reforming research assessments, whose new chair is the outgoing UU rector Henk Kummeling, also speaks out against using rankings when assessing research quality. According to UU, the International Association of Universities is preparing a statement about this.

Have some guts

However, Boselie must acknowledge that only a few universities in China, India and Europe have followed in UU and Zurich's footsteps. The University of Lorraine, which was not among the top 100, has done so too. No other Dutch or European university has abandoned the rankings.

According to Boselie, universities remain in the rankings for strategic reasons. In many countries, the government and other institutions fund universities based on their position or desired position in the ranking. ‘Sometimes, they are bound hand and foot.’

At the same time, many administrators and scientists ‘seem addicted’ to having a prominent place in the ranking. ‘It also comes down to leadership. A university's Executive Board must have some guts. And mind you, our Executive Board has shown that.’

It makes sense

Bert Weckhuysen, a professor at Utrecht University, also believes that rankings are often overrated and interpreted too literally. Nevertheless, he finds that UU has gone a bit too far by withdrawing from the THE ranking entirely. ‘You could say that we are leading the debate, but you could also say that we are isolating ourselves from the world.’

In his experience, the rankings do have meaning despite their shortcomings. ‘They might not be measured properly or completely, but these rankings are an indication of our relative position compared to other universities in Europe, the US and China. The list is not completely meaningless.’

The chemist points out that universities are in a global talent competition. The status of the university one has studied at or graduated from can play a decisive role in somebody's career, especially in Anglo-Saxon cultures. ‘That's why these rankings remain important, at least for now, for attracting staff, postdocs and PhD candidates. Conversely, the ranking also comes in handy for these people when they return or apply for jobs abroad.’

Elsevier

Some of Weckhuysen's peers abroad wonder if UU is shooting itself in the foot. ‘The name Utrecht does not immediately ring a bell for people in the US or China, but it helps when you say that the university ranks this high on such and such ranking. Students and parents want value for money and choosing the right university is very important.’

He draws a comparison with communicating with pre-university pupils who come to an Open Day. ‘If they ask how they can tell if a course is good, do you give them a padded answer? No, you advise them to consult Elsevier or Keuzegids, even though you know they could be criticised for all sorts of things too.’

Weckhuysen also remarks that almost all other universities continue to participate in the rankings, even the Dutch and Flemish universities that are critical of them. In his opinion, this should encourage UU to think about its strategy moving forward.

Taking the step

Epidemiologist Inge Stegeman is the chair of the Utrecht Young Academy and the coordinator of Open Science to Improve Reproducibility in Science (Osiris), a programme that investigates how Open Science principles can improve the quality of science.

She points out that no research has been done into the consequences faced by universities that drop out of a ranking. For this reason, she has a hard time understanding scientists who say that the decision has negative consequences for UU. ‘We have no idea what the effects are. Does it scare young scientists if a university drops out of a ranking? No idea. Maybe it's the other way around, maybe it attracts people.’

Stegeman is in favour of no longer participating in the ranking because the scientific landscape is changing rapidly. ‘It makes sense to leave rankings that do not measure what you want to be judged on. The fact that other universities have not yet taken the same step does not mean much to me.’

She thinks that UU's innovative research policy could also bring it international renown. People often ask her about it at international conferences. ‘Many researchers see us as a forerunner. They perceive UU as an example of the "new Recognition & Rewards” policy. I think we are forerunners who are also firmly rooted in reality.’

Alternatives

If you ask ChatGPT if UU is a good university, the answer is positive. The chatbot's number one consideration is UU's high position in the QS and Shanghai rankings. In a while, only the latter may remain, though.

Will that cost UU anything? Boselie doesn't think so. ‘I still hear that people like working in Utrecht and don't run away screaming. I think that's mainly because UU is so broad and focuses on research with social impact across disciplinary boundaries, which happens to fit in very well with contemporary scientific practice. Besides, it helps enormously that the board dares to make strategic choices.’

The Chief of Open Science emphasises that UU is not against all rankings. He underscores that universities don't need to provide data for certain rankings – take the Shanghai Ranking, for example, in which UU always scores well. But there are also better rankings, such as the ones made by CWTS and U-Multirank.

In his opinion, these two rankings are more interactive and offer comparison tools that go beyond a blunt ranking. After all, he knows that it is important for the university and its parts to compare their performances with other universities, albeit in a different way than is often done now.

‘There should be more differentiation by discipline. There are such large differences between faculties, departments and research groups that it is much better to break it down. In addition, you could look at the different domains. Research is not the only thing and is not the be-all and end-all. You could also look at the working atmosphere, to name but one. Finally, it is important to use benchmarks from which you can learn something. After all, that is what we ultimately want to achieve.’

Don't reject it

Bert Weckhuysen puts the search for alternative or better rankings into perspective. ‘The current rankings already allow you to make comparisons within all kinds of sub-areas, and there are more and more of them. Moreover, in my experience, every new ranking gets ‘gamed’ eventually. At a certain point, everyone knows exactly how they can score a good position.’

He supports the university's intention to establish itself as a champion in the fields of Recognition & Rewards and Open Science, but, in his opinion, this does not necessarily have to imply the rejection of current rankings.

‘Right now, the university is like: 'We are in favour of this and against that.' I think there is room for nuance. It's okay to be proud of your position on a ranking if you also indicate the ifs and buts. You can also try to gradually convince others of your narrative but, to do that, you need to forge a strong alliance with universities at home and abroad and that takes time. Top universities in the US will not be quick to follow suit. They are like Coca-Cola brands, you are actually going against their business model.’

‘Proud to be appreciated by colleagues’

How can universities compare themselves to others if they believe that their position in the rankings says little about what is going on inside of them? And what about those who believe that one can learn from benchmarks?

In recent months, a report comparing several countries on the valuation of education provided by research universities has often been cited as an example of how things could be improved. The qualitative study Rewarding Teaching in Academic Careers: Mapping the Global Movement for Change showed that interviewees cited Utrecht University as the most remarkable example among all universities.

UU was characterised as a ‘global pioneer’ when it comes to supporting and appreciating university education. Educational culture and practice have become part of the organisation's DNA.

It was well known that Utrecht is highly regarded in the world of education. UU is the founder of the basic teaching qualification for university lecturers and a course in educational leadership. The university also designed the triple model for the assessment and promotion of employees, which offers a lot of scope for careers with an emphasis on education.

‘Although we still have a lot of steps to take in Utrecht, we are proud to be appreciated by our peers for the educational ecosystem we have built over the past thirty years,’ says Manon Kluijtmans, Vice-rector of Education at UU and founder of the university's Centre for Academic Teaching.

‘We know that other universities have adopted many of the things we have developed here. That's the best thing: when others do the things you do well.'

According to Kluijtmans, the desire to learn from other universities has also been the main motivation for the research carried out by the renowned Ruth Graham. UU took the initiative alongside six other universities affiliated with the Advanced Teaching Network, an international network conducting annual surveys on the satisfaction of teachers regarding the appreciation and support of their work. In Utrecht, the support for education scores relatively high, and teachers are increasingly positive about the appreciation of their work.

Kluijtmans: ‘That is interesting information, of course, but it is also clear that there is still much to be gained. We asked ourselves: What should we be aiming for and how can we achieve it? These surveys only give us the perspective of the teacher. We also wanted to know how other universities improved their educational culture and who we could use as an example.’

She believes there is much to learn and be inspired by in the new report. In Singapore, universities look very carefully and thoroughly at the extent to which teaching contributes to student learning. In Canada, teachers are expected to be committed to an inclusive and equitable learning and working environment. ‘It is truly an integral part of the performance evaluation there.’

A word by this week's guest editor-in-chief, Henk Kummeling:

This week marks the departure of Rector Henk Kummeling, so DUB invited him to be a guest editor-in-chief for a week. He suggested several themes for in-depth articles, and DUB's editors then delved into them. Kummeling explains his reasoning for suggesting an article about the university's reputation after leaving international rankings:

'In recent years, we have done a lot in the field of Open Science, and we have decided to no longer submit data to certain rankings. The question "What is our reputation regardless of rankings?" is a relevant one for me. I have my own ideas about this, of course. I believe that we achieve our greatest impact through education, through the talent we educate for society. The number of grants we receive is another indication of how our research is valued. But I was curious to see what a journalistic search by DUB's editorial team would yield. It is nice to read that colleagues feel that the Executive Board was brave when it decided to drop out of certain rankings. I hope and expect that renowned universities that are critical of rankings will soon follow our lead. Of course, there are concerns, but we can find solutions to those.'