From UU student to best-selling author

Writer Peter Buwalda: 'My time as a student in Utrecht was a bit schizophrenic'

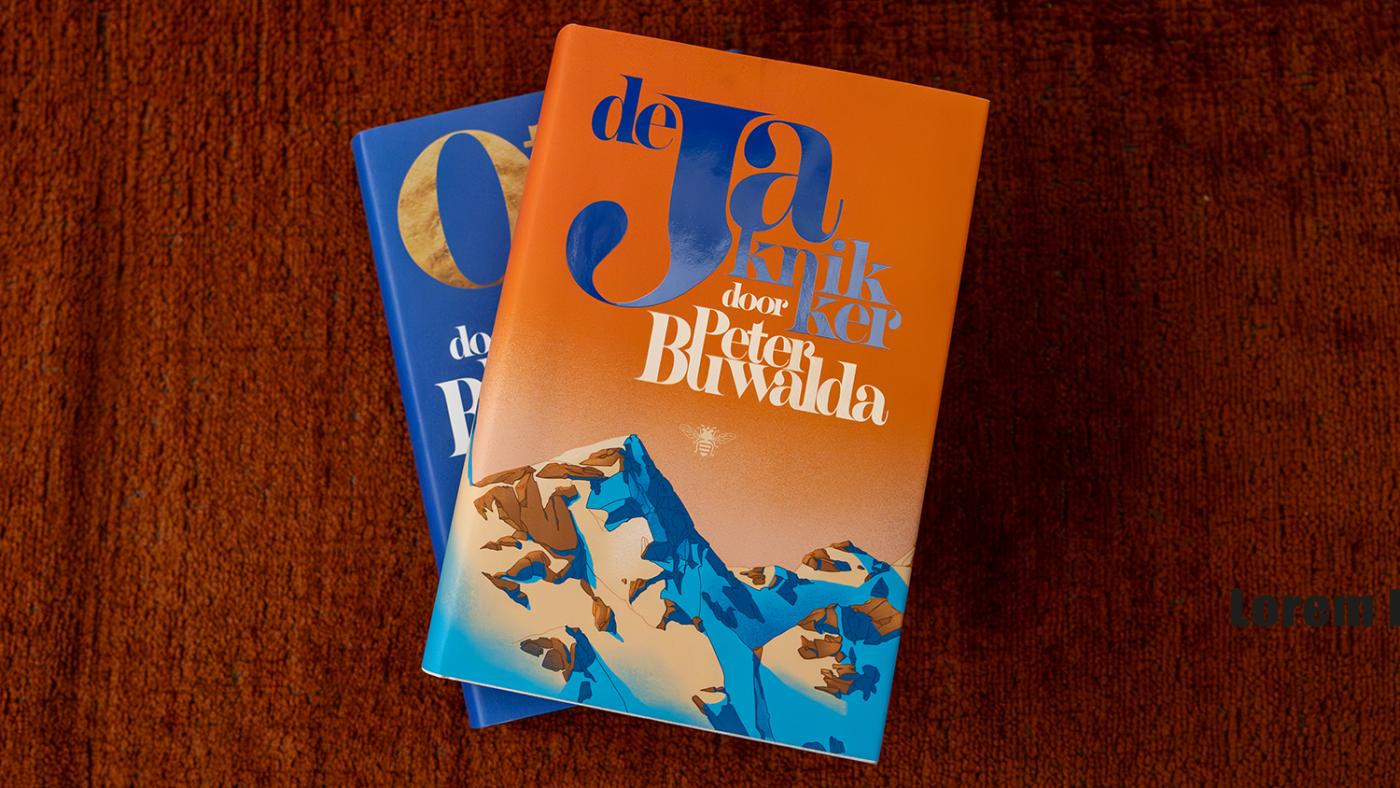

Peter Buwalda would have liked to answer the questions now, but a driver is waiting to take the writer back to his home in Breda in 10 minutes. He is in Utrecht on a promotional tour for his new book, De Jaknikker, which he is kicking off at the Broese bookstore.

There is a good reason for this. Before he became a best-selling author and columnist for the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, Buwalda was a Dutch language student at Utrecht University. At the time, he did not see himself becoming a writer, however.

After graduating, he worked as a reporter for the university newspaper in Twente and then as an editor at a publishing house in Amsterdam. His writing debut came in 2010 with Bonita Avenue, a page-turner about a rector who falls from grace in disastrous fashion. The book won all the debut awards, sold 400,000 copies and was translated into twenty languages. Nine years later, he published Otmars Zonen (Otmar's Sons), the first part of a trilogy about a father and son who lose sight of each other. The second part, De Jaknikker (The Nodder), was published last October.

Two weeks later, I am sitting opposite the author in Breda. It is hard not to be distracted by his “Jurassic Cupboard” towering above his head. It is a custom-made shelf 6 metres high and 12 metres wide, filled with around 10,000 books. It reaches up to the ceiling and even extends over the mezzanine. It is an impressive sight that makes one thing clear: the writer is, above all, an avid reader.

Why did you choose to study in Utrecht?

"I wanted to study physics, but I was also quite an artsy type. For example, I always enjoyed history. And at a fairly late stage, I discovered a kind of sparkle in literature. I avoided the reading list until I had to read two books that really grabbed me. De donkere kamer van Damokles (The Dark Room of Damocles) by Willem Frederik Hermans and Een nagelaten bekentenis (A Posthumous Confession) by Marcellus Emants. For the first time, I noticed the shift you experience when you are truly immersed in a book. So then I thought, to be on the safe side, that I should go to a university that offers both science and arts programmes. UU did.”

How were your first few weeks?

"I joined Unitas, without really knowing why. That turned out to be very intense. As a result, the first few weeks of physics really passed me by. I was often late for lectures, exhausted, and sometimes even half-drunk. The pace was fast right from the start: my first course was about the theory of relativity, and Einstein's head was on the syllabus.

At the same time, the memory of those two books started to resurface. After six weeks, without consulting anyone, I dropped out and started studying Dutch next door. That same day, I walked into a bookshop and bought ten novels by Vestdijk, even though I had no idea who he was. I could tell from the way the books looked that they were important.

That's how little I knew about literature. I was completely clueless. But I was determined to make it a success, so I started reading like crazy. I've never stopped since."

What were you like as a student?

"I was provincial. I grew up in Blerick, in Limburg. My parents hadn't studied. I didn't know much about university. Throughout my student days, I actually felt a bit schizophrenic. I was very interested in Dutch, very ambitious. I also wrote for the magazine Vooys. Dutch students thought you couldn't have serious plans with literature if you were a member of Unitas. And, at Unitas, being serious about literature was taboo. It was never about literature there. In my year club, only one other person read. Unitas was more like a wild bunch, which made me feel like a stowaway in both places."

Did you already know that you wanted to be a writer?

"No, I only figured it out some time later. Studying Dutch made me love literature very much, but more out of admiration. In the Dutch programme, books were also treated as works to be admired. It was as if they were some kind of meteorite that had fallen from the sky; that's how we approached The Dark Room of Damocles, for example. Above all, they made clear that you shouldn't think you could write a book yourself. In a way, that makes sense; it's the raison d'être of the programme. Why would you study works of art that you could create yourself?"

Would you study Dutch again now?

"Yes. Otherwise, I would never have found my way into literature; that whole network of writers, books and oeuvres. It's a kind of underground metro system of thoughts, impressions, styles and characters. What worries me is that fewer and fewer people have the patience to read novels. Reading has been reduced to a smaller group of initiates, a kind of Freemasons."

Why do you think fewer people are reading now?

"Convenience. Junk on your phone. When I was studying, you couldn't watch all of Messi's goals. It's a temptation I have to resist, too. That takes energy. I can imagine that if you grew up with that, it takes a lot more effort to concentrate on something difficult."

I can imagine that the internet has been very useful to you in terms of research.

"That's true, but that's also where the danger lies. You surrender yourself completely to endless amounts of information and websites. It becomes a kind of task to stay away from it, a certain muscle you have to train."

Otmars Zonen and de Jaknikker are set in Nigeria and Siberia, among other places. Have you been there?

"No. Not going there felt like a stupid idea at first. I was about to go and live in Siberia for six months. But doing research that way can also work against you. If you know too much about something, you have a very strong image. Then you can't test whether that image comes across to readers. Whereas if you know nothing, you can write something down and then, when you read it back, you can test whether it gives the impression that you've really been there.

I once wrote about Trompetsteeg in Delft. It hasn't existed since 1993. But I was able to describe it using photos from the 1950s. I then received a letter from an old man who was born there. He was certain that I had grown up in Trompetsteeg! For me, that was proof that I didn't need to go to Sakhalin."

You worked on The Jaknikker for six years. What is it like to wake up every day and have to sit down and work on the same book?

"Now I can hardly imagine it anymore, but actually it's a lot of fun. The absorbing problem you're faced with, working your way towards a solution, editing and polishing the text. Time just flies by. Writing, then sitting in pubs, chatting with everyone, then back again: I couldn't do it anymore. I don't like being interrupted. I do it sometimes, but then I feel miserable the next day, staring blankly at my laptop. While you're writing, the book is still a mess, and it's hard to imagine anyone wanting to read it. If you're interrupted too often, you'll start to feel that way too. It's like standing waist-deep in a swamp; you don't want the mud to set."

Were you just as single-minded about your studies?

"No, I can't be persuaded to do anything else."

Will you keep writing until you die?

"I think so, yes. I think that's one of the nice things about being a writer: you can keep doing it until you get dementia. There are also real examples of writers who only reached the top after the age of 65: Philip Roth, Wessel te Gussinklo. I think that's a nice prospect."

The days are getting shorter, and the Christmas holidays are approaching. Do you have any book recommendations for the winter?

"Always. The Road by Cormac McCarthy, which is very dark and wintry. Augusto by Alberto Moravia, a very warm and sunny book. And The Mine by Emile Zola. It's a thick one, but what a fabulous novel!"

Comments

We appreciate relevant and respectful responses. Responding to DUB can be done by logging into the site. You can do so by creating a DUB account or by using your Solis ID. Comments that do not comply with our game rules will be deleted. Please read our response policy before responding.