Caribbean students experience study delays more often

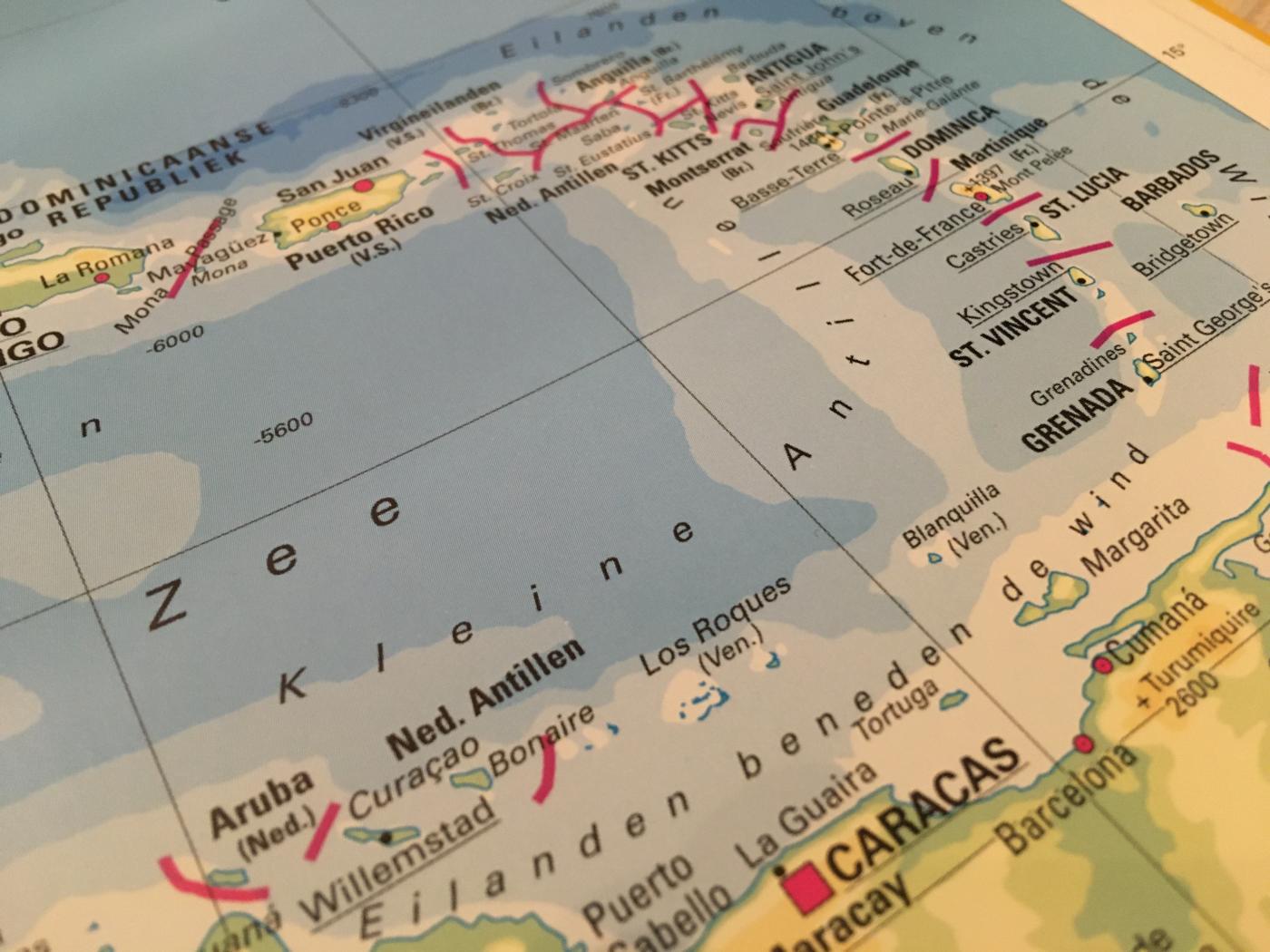

Not all international students know that the Kingdom of the Netherlands extends to the countries of Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten, as well as the cities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba, all located in the Caribbean. This means that people born in these locations are Dutch citizens, too – and many of them (around 1,600 a year, to be more exact) come pursue their higher education here.

But, even though they’re spared from the immigration bureaucracy other non-EEA students have to face, their experience in the Netherlands is far from easy, according to the report Kopzorgen van Caribische Studenten (Main concerns of Caribbean Students), published by the National Ombudsman and soon to come out in English and Papiamento.

“It is survival of the fittest,” says 24 year old Karman from Bonaire. “The culture is completely different from that of the Antilles. Here you really have to stand up for yourself and arrange everything yourself. In addition, you have to cope with loneliness and the prejudices people have about you.”

Stuck

According to the report, their studies don’t move forward for several reasons. Besides not knowing what to expect from the Netherlands, having to find a place to live and figuring out the public transport system, Caribbean students often start their studies lagging behind Dutch classmates in terms of language skills. Universities and universities of applied sciences expect students to have a high level of Dutch proficiency, which isn’t easy when their home country speaks a combination of English and Papiamento.

But that’s not all: Caribbean students do not receive a social security number (BSN in the Dutch acronym) and a DigiD upon arrival, which makes it hard for them to get important affairs in order, such as registering their address at the municipality. In addition, the Caribbean Dutch are not entitled to receive a healthcare allowance. If they apply for this benefit (and receive it) without knowing that they were not eligible in the first place, they’re asked to give all the money back at a later date.

A different sense of humour

But perhaps the most important thing is that the Caribbean Dutch aren’t always received with open arms by the “blonde and blue-eyed” Dutch classmates, who are sometimes prejudiced and come off as too blunt and direct. The different sense of humour also makes it hard for Caribbean students to fit in.

This often results in Caribbean students feeling like second-class citizens, warns the report. That’s why they’re more likely to suffer from psychological problems, experience study delays, or drop out altogether.

Taking action

The Cabinet should therefore take immediate action to tackle this problem, the National Ombudsman wrote to the Minister of Education, Ingrid van Engelshoven. The ombudsman suggests, among other things, that Caribbean students should receive more information and psychological counselling, as well as being granted access to the Dutch health insurance and health care benefits. Lastly, there should be a better system in place for them to pay off their student debt.

The National Ombudsman’s study surveyed 624 Caribbean students through in-depth interviews and round table discussions. The results were shared with over fifteen organisations, including the Ministry of Education, student financier DUO, student housing providers, and parties overseeing Caribbean students.