Internationalisering: figures, pros and cons

The Netherlands is a favourite study destination for international students: almost 86,000 internationals are currently enrolled in full Bachelor’s or Master’s programmes at Dutch universities and universities of applied sciences. They represent no less than 11.6 percent of all students, a figure that has doubled over the past ten years. Most international students come from Germany, closely followed by Italian, Chinese, Belgian and UK nationals.

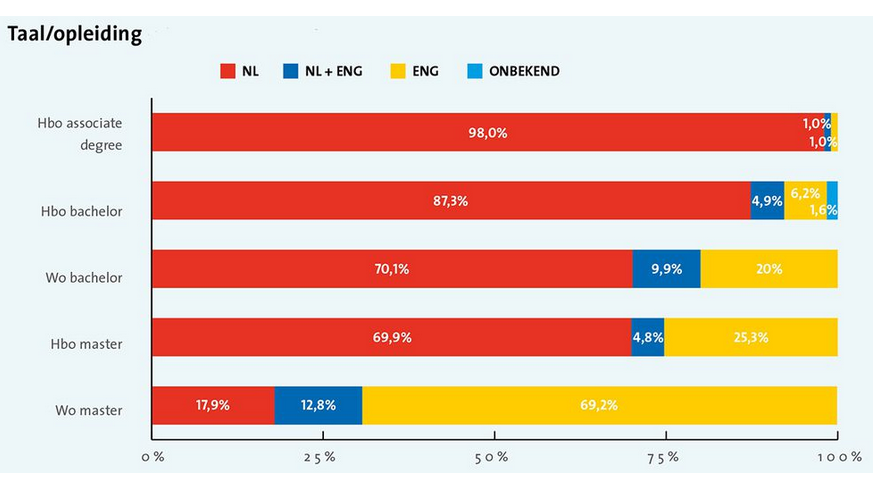

The most popular institution for international students is Maastricht University. The University of Amsterdam and the University of Groningen are in second and third place respectively. Utrecht University is in tenth place. The most popular study programmes include International Business, Psychology and Business Administration. English is the language of instruction for a relatively large number of Master’s degree programmes: 25.3 percent at universities of applied sciences and 69.2 percent at universities.

For good reason

There has been much ado about the language policy at institutes of higher education. Institutions offering programmes taught in a language other than Dutch are required by law to substantiate this decision in a code of conduct. An inspection report issued at the start of 2019 showed (link in Dutch, ed.) that almost half of Dutch institutions had not met this requirement. Since then, however, they have made considerable improvements.

The education minister’s legislative proposal includes more stringent supervision of the language requirement in higher education programmes. These programmes should be taught in Dutch, unless there are good reasons to deviate from this standard, for example because graduates might otherwise struggle to find employment after graduation or because English is the working language in a specific sector.

Universities are very unhappy about this measure and fear it will result in “a considerable and unnecessary increase in the workload” if they are constantly required to clarify their decision to opt for English-language programmes. It also remains unclear whether higher education watchdog the Accreditation Organisation of the Netherlands and Flanders (NVAO) will take action against institutes that fail to meet the requirement.

The minister has a second plan for limiting the influx of international students: she wants to make it possible to place enrolment restrictions on English-taught variants of programmes, while the Dutch-taught variants will remain accessible to everyone. At the same time, she wants to protect and preserve Dutch as a language of culture and science. She believes even international students should learn Dutch to some degree.

Funding

A quick reminder: what are the minister’s reasons for wanting to limit internationalisation and anglicisation? Advocates argue that there are plenty of advantages as well. Institutes of higher education are happy to welcome international students because more students means more government funding. Institutes in shrinking regions are particularly eager to welcome international students, as are local business communities which face potential shortages in the job market.

The Dutch government also benefits financially from international students, revealed the auditors at the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis earlier this year: on average, students from other European countries bring in approximately €5,000 if they attend a university of applied sciences and €17,000 if they attend a university. For students from outside Europe, the benefits to the Netherlands are considerably higher: €68,500 if they attend a university of applied sciences or €96,000 if they attend a university.

Dutch students may also benefit from being part of a more international student body. Finding their footing in the international job market may be easier for them if they have the chance to learn more about other cultures and piggyback (in Dutch, ed.) on the academic success of often ambitious internationals.

Crowded out

Opponents view things differently. They believe that English-taught lectures have a negative effect on Dutch language and culture, and that nuance and depth are lost when students and lecturers lack proficiency in English. Some claim that universities are also unable to cope with the influx of international students, since funding for research does not increase in proportion to the number of students, resulting in increasing student numbers per lecturer. In larger classes, personal attention is therefore more likely to be in short supply.

Critics claim that all those international students are also crowding out Dutch students. Last week, the Inspectorate for Education tentatively concluded that programmes with restricted enrolment are becoming less accessible, especially to women, students from low-income households or students from a non-western migration background. While internationalisation does not currently appear to have a negative effect on accessibility to regular programmes, the Inspectorate added “we do not know to what extent an increasing number of students may have to settle for a degree programme or university that is not their first choice.”