Structural overtime academics leads to stress, sleep deprivation and relationship problems

In December, the protest movement WOinActie asked academics to describe problems they were experiencing as a result of the workload at universities. Their intention was to bring a collective complaint to the Labour Inspectorate, and that complaint was delivered today.

“We expected something like 100 complaints,” says Ingrid Robeyns, a lecturer in Utrecht and one of the group’s representatives. “We got more than 700. And that’s in December, which is a busy month! That gives you an indication of the scale of the issue.”

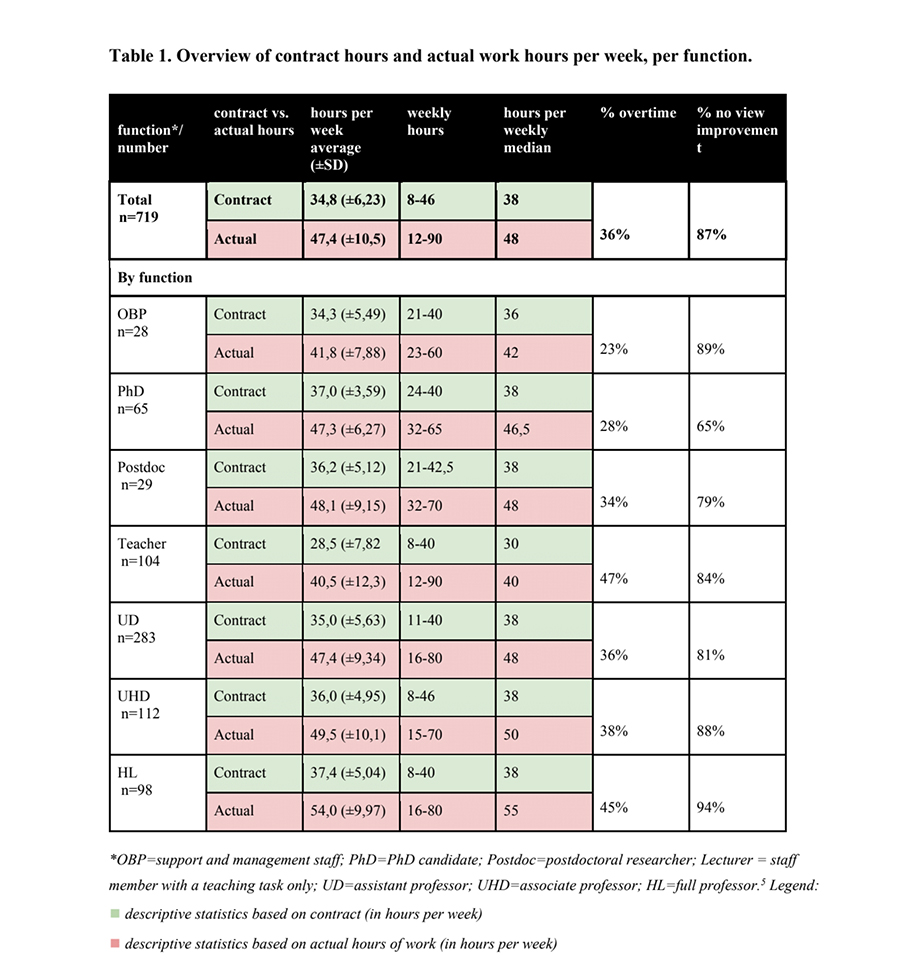

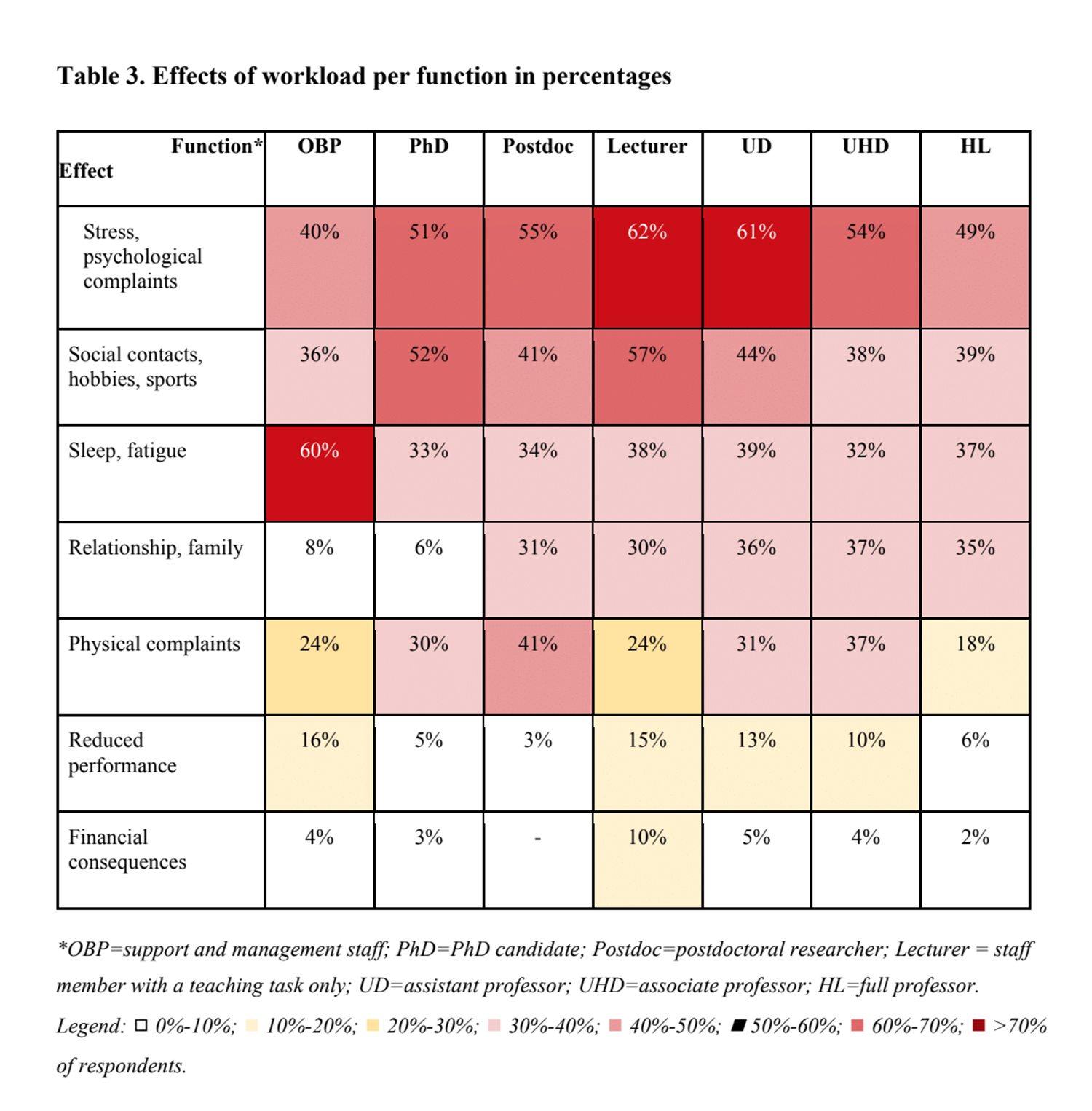

The complaints have been brought together in a brief report. The employees who responded to the call said they structurally work around 12 to 15 hours of overtime a week. Professors and teachers with an education-only position tend to work the most overtime (an average of 45 percent overtime), followed by senior lecturers (35 percent) and employees with a research-only contract (30 percent). Administrative staff say they work overtime 25 percent of the time.

The most common reasons given for working overtime are having more and more tasks, and the increase in the number of students. The education hours, especially, are not sufficient for the amount of work that needs to be done. On top of that, the time reserved for preparing classes, teaching classes, maintenance of the digital learning environment, keeping up with literature, and providing students with feedback has decreased in the past few years. There are peak periods, around exam weeks for instance, that tend to be especially busy. For other education-related tasks, no time has been reserved at all, and yet employees are expected to do them. These tasks include developing new courses, further training, committee work, and surveillance.

For employees who both teach and research, the research tends to be done in the weekends of evenings. Scientists also experience more stress because they feel pressure to perform, and often have to fight for an extension of their contract by submitting research proposals.

Among the issues academics report are a lack of sleep, marital problems and stress. “One of my children has developed a fear of failure, possibly partly due to my situation and the signals I’m giving off,” one person writes. Other contributors also brought up the effect the problems are having on their family and their health: “High blood pressure, poor sleep.”

Strong work ethic

“Academics have such a strong work ethic that we end up damaging ourselves,” says Robeyns. “The government takes advantage of our passion, and politicians can get away with it because we’re such loyal employees.”

Do these complaints reflect the situation of the entire university community? No, says Robeyns: WOinActie’s report is not a scientific study, but rather a collection of complaints. However, those complaints present a shocking picture.

Universities use ‘standard hours’ for teaching and other duties, but there are never enough hours allocated. Robeyns explains that this has financial consequences, too: “Some employees are on a 0.7 FTE contract, even though in practice they work full time.”

Universities have proposed a raft of plans to reduce their employees’ workload, but WOinActie says those plans are not being put into practice. Some also offer academics a course in time management. “That puts the responsibility on the researcher, as if everything will be fine if you just plan your time better.”

Ultimately, the group is aiming to achieve €1.15 billion in structural investment for academia. But will that help with the workload, or will it just add even more work?

Questions for labour inspection

The report was presented to the labour inspection on Monday morning. The inspection is asked specifically to conduct research on the ‘norm hours’ system. Are the demands universities are making of their scientists realistic? A second specific question the report asks of the inspection is to conduct a study on the extent of ‘grey absenteeism’, or illnesses that aren’t registered. The supposition is that a lot more teachers are dealing with burnouts than is currently stated in the university’s reports.

More teachers

Robeyns explains that although extra funding is needed, it won’t solve the problem on its own. “If the money comes in the form of another new research agenda that makes academics compete for funding, that won’t be any help. It has to go directly to the universities, to benefit teachers. No extra management, no PR officers – more teachers. And we have to get rid of the distrust, the idea that they don’t work hard enough.”

Robeyns has personal experience of the problems outlined in the report. “I worked every evening last week. On two nights it was after midnight before I went to bed, and then I was up again at 7. You don’t get enough sleep that way. I work about 55 hours a week, and I know that because I recorded it over a certain period – without that record I could have been exaggerating the problem. The result is that I don’t exercise enough, and I don’t relax enough. I’m 47 now: I don’t know if I can keep this up for another 20 years.”

Her work for WOinActie is an extra burden. “You might say I do it to myself, but I think what we’re doing is really important, and I think we can achieve our goal. Even the minister says another billion euros is needed.”

Looking for another job

Robeyns’s children have also noticed how hard she works. “One of them said recently: Mummy, can’t you resign and find another job? Sometimes that’s a very attractive prospect. But I’m passionate about teaching and research; I love teaching young people.”

She also enjoys supervising PhD candidates, “but I do get an uncomfortable feeling sometimes – what will their future be like? And there’s no point moving to a university overseas, because the situation is the same there. I’m speaking as a political philosopher now, but this is a result of the neoliberalism that’s moving through Europe and America. We’re living in an era when the public sector is underfunded, which means that academia is underfunded too.”

“The results of this report are shocking and familiar at the same time,” says Bart Pierik, spokesperson for the association of universities (VSNU). “You can see the consequences of 15 years of insufficient funding of higher education.” He thinks the VSNU can use this report as ammunition in the fight with the ministry and politics. “The Netherlands has seen a great increase in the number of students. That’s great, because it means more people have the opportunity to go to college. But if that’s something you want as a country, you also need to accept that that costs money. This report painfully shows what the consequences are of accepting more students, but not investing enough in it.”

Pierik isn’t only pointing at the government. The universities themselves are also acknowledging the problems, and have been working for years to battle the pressure to perform. Recently, an agreement was made with the NWO to arrange the pressure on science in a different manner. The universities have also been given the assignment of creating a plan of action for battling workload pressure. That includes, for instance, looking carefully at teachers’ tasks. It’ll take time, however, before most of these measures have tangible results.

The UU plan is also published on the VSNU website. The Executive Board dedicated the Start of the Academic Year in September 2018 to workload pressure, and states that the subject is a priority for the board. The UU wants to tackle the issue by, for example, investing money in hiring more teachers, and giving temporary teachers long-term contracts. The UU also says it wants to work on creating a different culture, investing in a leadership programme, and putting less pressure on publications, making team work more important than individual achievements. Each faculty has introduced initiatives to help relieve some of the workload pressure.

The Executive Board calls the WOinActie report a ‘cri de coeur’ that emphasises the importance of dealing with workload pressure. It’s the national government’s time to act on this, but the university should also do whatever is in its power. This coming year, the university will evaluate its current approach to workload pressure.