Tumultuous tender process for course evaluations means the end for Caracal

In an internal message on the tender process posted this week, Information and Technology Services (ITS) and Academic Affairs eat some definite humble pie. They claim to ‘realize that in this process, things went wrong several times, and expectations were raised’. They also express their apologies to ‘all people and parties who put their time and effort into this’.

The entire course of events definitely leaves a lot to be desired. Last year, to the surprise of many, the UU decided not to choose the system that had the best test results – Caracal, developed by UU programmers. This week, it became known that the process of granting the contract to external provider DiCe didn’t meet the formal requirements. Although the UU had already communicated the news of the new provider in several places, the entire tender process has to be redone. The university expects to be able to announce the provider that’ll take care of UU’s digital course evaluations no sooner than June this year.

Choosing against Caracal

So what happened? Early last year, the UU started its search for a uniform system that could process student evaluations on both courses and teachers for all study programs. The search was prompted by the faculties, who were eager to see a system that could work alongside the university’s IT department – as opposed to the current situation: several different systems are being used simultaneously right now, that are all the responsibilities of the separate faculties’ IT people.

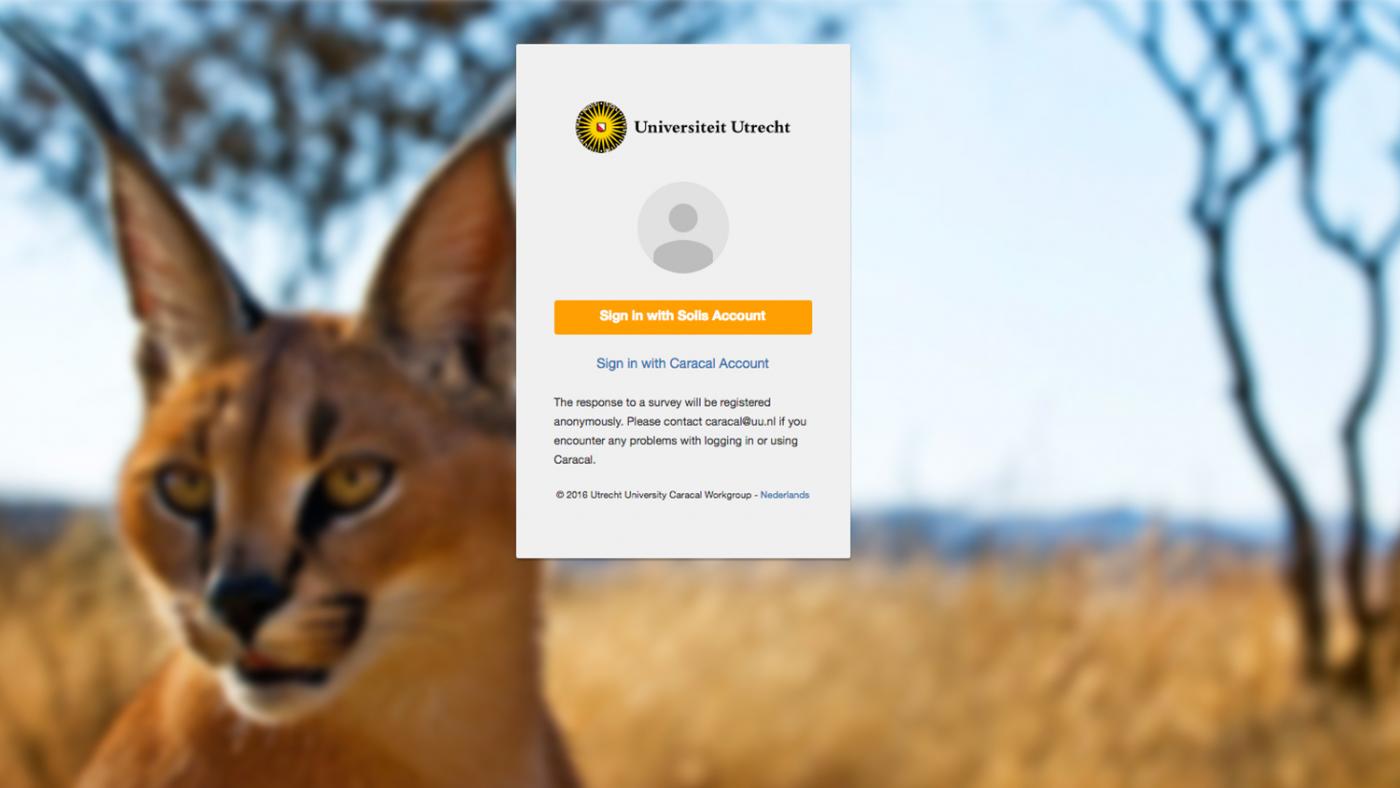

At first, tests among three systems showed Caracal to be the best. It’s a system that was developed by the UU’s own programmers, no less. Caracal is already in use by the faculties of Science, Humanities and on a smaller scale the faculties of Social Science and Law as well, to general satisfaction. To the surprise of many, the university’s board decided against using Caracal late last year. They chose the external provider DiCe.

Rector Bert van der Zwaan explained the decision in a meeting with the university council late December. To his own frustration, the board had been forced to go against its own initial choice of using Caracal. Van der Zwaan claimed there’d been a ‘hole in the decision making’. They had not sufficiently looked at safety criteria and the long-term exploitation of the system, which led to an excessive risk to company security. Additionally, the university’s policy, which states it preferably opts not to use software developed in-house, had not been taken into account enough.

The course of events led to more than a little incredulity within the university, mostly among the Science staff. Marjon Engelbarts, head of IT at the faculty of Science, said in an email response that all her employees, despite their own appreciation of DiCe, were ‘somewhat shaken’ by Caracal’s rejection. She says it’s easy to get the impression that the system’s quality and security aren’t okay, whereas according to her opinion, it’s a product that’s stable in both technology and organization, and it isn’t even expensive. “We use the common technologies, and we’re always making sure everything meets the newest criteria, regarding privacy and security as well.”

Engelbarts says it’s ‘a shame’ Caracal is being ‘thrown out’ without exploring what it would mean to expand the system technology-wise as well as financially.

Admitting blame

Explaining the course of events to DUB, Carolien Besselink, director of Information and Technology Services (ITS) and Esther Stiekema, director of Academic Affairs, said last month that the board’s decision shouldn’t be seen as a disqualification of Caracal. The decision was tied to the university’s principle of not competing with commercial providers when it comes to tailor-made software products.

Besselink: “In a course evaluation system, it’s not about a unique functionality. It’s about a mature market with a sufficient number of providers of good and secure products. When you look at efficiency, costs and security, we then prefer choosing an external provider over having to bring all that specialist expertise to us. We’d rather use the limited capacity we have for the university’s core businesses, research and education. Even if that means having to give up a little bit of customization and flexibility.”

But why, then, was Caracal even allowed to tender? Before the process started, the ITS board had explicitly mentioned that Caracal could qualify despite the university’s policy. That increased the incredulity that followed the choice not to grant the contract to Caracal.

Besselink and Stiekema admitted the faults. “Yes, that process didn’t go right,” Besslink admitted. She wasn’t able to say why Caracal had been mentioned as an eligible candidate before the systems were compared. Stiekema says the university had to learn from the way the decision was made. “Before starting a tender like this, we should examine the question at hand. What exactly are we looking for? What does the market look like?”

This week, however, it turns out that wasn’t quite the end of it. After having rejected Caracal and exploring the three external software providers, technicalities surfaced that ‘could have legal consequences’. The university board therefore decided to retract the contract with DiCe, and redoing the tender.

The plan is to eventually have one system that will be used by all faculties. “It’s not our intention to swim upstream,” Marjon Engelbarts of the faculty of sciences IT says. “When another system has been implemented at other faculties successfully, and it’s functioning well, the faculty of Sciences will gladly conform and say goodbye to Caracal.”

Not comparable to Osiris

To many involved people within the university, the question remains which software you get from external sources and which software is best developed within the university. Besselink and Stiekema state that custom-made software developed by university staff isn’t always not-done. Specific software, developed for a specific issue within research or education, will still be possible. Besslink gives the example of YODA, a storage system of scientific data that was set up by the university’s IT staff. “Software like that isn’t available anywhere else, but offers a great value to the university’s strategy.”

Besselink says Caracal cannot be compared to study registration system OSIRIS, which was once developed at the UU and is now also used by other educational institutions. “There was nothing like it when it was developed. There were no other providers. In a situation like that, you have to do it yourself. In a course evaluation system, that’s definitely not the case anymore.”

“I’m struggling with the fact that all these administrative systems used at the university are outsourced to external parties. That development has sadly been going on for years. There are all sorts of commercial services that work with our students’ and employees’ data. It may be more efficient – although I doubt that, too – but it’s not right, in my opinion. Plus, it makes the open nature of the internet rapidly disappear. I’m a big supporter of grassroots software that can be freely developed further by anyone.”

(Translation: Indra Spronk)