Academics under attack

Under the watchful eyes of Sarah Roosevelt whose portrait beamed down at the audience at the launch of the Free to Think 2017 report by the Scholars at Risk network at Roosevelt House in New York City, I thought – as I have been doing virtually every day since getting to the US – how depressingly little seems to have changed in the seventy years since Eleanor Roosevelt chaired the UN Human Rights commission that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

I know full well of course that life has vastly improved since the 1940s: life expectancy has risen tremendously, there are fewer people in poverty and despite our fears over terrorism, fewer people die a violent death than decades ago. The New Optimists like Swedish historian Johan Norberg have pointed out as much. Much of the reason for positive human rights development is thanks to the United Nations, the conventions it has got countries to sign up to and to the actions of brave citizens, political leaders, activists and NGO’s. But there’s a long way to go and sometimes it feels like we’re taking only one tiny step forward and two steps backwards. In a time when populism and totalitarianism seem to be on the rise again, we have got to guard against the backward steps not becoming gigantic leaps.

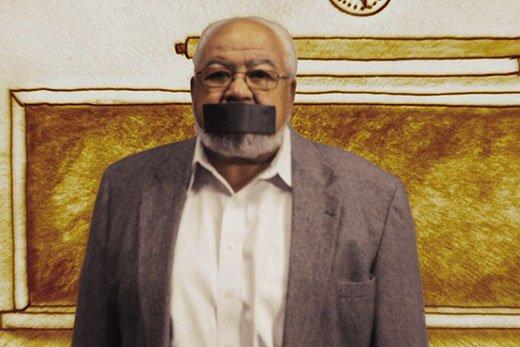

As a media scholar, I am used to seeing the annual reports on press freedom by Reporters without borders and Freedom House. Their 2017 reports don’t make for happy reading: Press Freedom’s Dark Horizon was the headline of Freedom House’s assessment as global press freedom fell to its lowest point in 13 years, while RSF went with Journalism weakened by democracy’s erosion. I was less aware of the bleak picture regarding academic freedom in many parts of the world. The Free to Think 2017 report by Scholars at Risk details various types of attacks on higher education, including killings, violence, imprisonment, job firings, travel restrictions and severe or systemic issues such as university closures.

At the launch event entitled Anti-Democratic Trends and the University Space, which took place in the former home of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt on East 65th Street (and now houses the Public Policy Institute of Hunter College) a panel consisting of Laura Christina Dib Ayesta (Masters student of International Human Rights and student activist Venezuela), Jonathan Cole (Professor at Columbia University and author of many books on academic freedom), Raza Ahmad Rumi (Scholar, author, policy analyst, and journalist), and Robert Quinn (Executive Director of Scholars at Risk) outlined the situation in four countries – Venezuela, Hungary, Pakistan and Turkey – and spoke about what ties together these very diverse contexts: a desire on the part of some people, sometimes governments, but certainly not always, to control or silence thinking and dissenting voices.

Laura Christina Dib Ayesta explained how dire the situation is in Venezuela with students who protest the government being shot (120 killed since 1 April 2017) or detained (this year already 5000 protestors). Just this week medical students were detained for posting a photograph of a woman giving birth in the corridors of a hospital. What will happen to them for putting the government’s health care system in a bad light?

Raza Ahmad Rumi related harrowing stories of campus violence in Pakistan, such as the murder of Mashal Khan by his fellow students who accused him of blasphemy for certain comments he’d posted on his social media account. Rumi warned that there seems to be a rise in bigotry in many countries. But he also urged the audience to look at two other factors that hindered academic freedom and freedom of thought: the growing trend in the US (but this is certainly also the case in the Netherlands) of not giving university faculty tenure so they’re potentially afraid to exercise academic freedom lest they lose their temporary job, and the underrepresentation of non-white people on student boards and among faculty ranks.

Jonathan Cole spoke about the problems facing the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary, where the government of Prime Minister Victor Orban, has amended the national Higher Education Law. The new provisions have thrown up so many financial and administrative burdens that CEU may cease to exist. While there’s no threat of violence, the moves by Orban’s government seem intended to punish CEU for its affiliation with the Open Society Foundation of financier and philanthropist George Soros. As Cole said, ‘Academic Freedom is an indicator of the state of liberal democracies, and ideas discussed in universities are intended to be upsetting to students and governments.’

Robert Quinn of the Scholars network stressed that the cases highlighted in this year’s report were just the tip of the iceberg. He was particularly worried about the situation in Turkey where since the attempted coup in 2016 some 7000 academics have lost their jobs and 400 have been charged with crimes for which there is no evidence or there are trumped up allegations. The fact that a country that only a few years ago was making such headway on human rights has seen such an abrupt change should make us all aware that freedoms, including academic freedoms, have to be continually fought for: complacency is dangerous. And it's not just complacency that threatens our academic institutions and democracy; the seemingly growing desire to protect ourselves against ideas we might find offensive is having an effect on people's willingness to engage with each other. Particularly in the US, Quinn advised, universities need to get away from the binary divide of free speech versus hate speech, of whether to invite controversial speakers to campus or to play safe. Quality of the speaker’s research and arguments should be the criteria instead.

I wonder what Eleanor Roosevelt would have said if the live version of her had been present in the room (rather than the quiet bust of her that was there). “It is my conviction”, she wrote in Tomorrow is Now, “that only the power of ideas, of enduring values, can keep us a great nation. For where there is not vision the people perish.” ER used to come to talk to the students at Hunter College often when she lived in the city and most certainly would have approved of the current generation of College students who have formed a chapter of Scholars at Risk.

Merely guarding against infringements of freedom, whether of journalists or academics or any other profession that is vital to healthy democratic societies, is no longer enough; instead we scholars and citizens, both individually and collectively in our institutions need to push back on those infringements: talk about our values openly, engage in discussions with those whose opinions we don’t share, and show that the best universities value the power of ideas. It’s heartening that my home institution Utrecht University is part of the SAR network and that Presidents of all Dutch universities earlier this year wrote a joint letter to a national newspaper about their concerns about the freedom of science, but we need to do more. “Remaining aloof is not a solution”, ER would have argued; if each man or woman takes a small step, together we can make giant leaps forward for mankind, rather than risk drastic backward movement.

This blog was published on the personal website of Anya Luscombe last week.