Lack of willingness to engage

Classrooms must become spaces for honest dialogue

Politics plays a significant role in shaping our future, often influencing our lives beyond our direct awareness. The youth now have the voice and power to influence democracy; therefore, they should not shy away from political conversations but use them to develop critical thinking skills. Classrooms should become places where we actively welcome and encourage political dialogue. Not to polarise, but to have conversations about understanding, acknowledgement and empathy.

I had the privilege of attending an international school throughout the first 14 years of my education, and now I am pursuing an internationally inclined Bachelor's, Global Sustainability Science. Having experienced these varied educational environments, I have come to believe that classrooms are the places where unique perspectives, shaped by different national, cultural, social and lived experiences, intersect.

As university students, we have the privilege of being exposed to these diverse, sometimes unheard, viewpoints. For instance, hearing a classmate from a conflict-affected region share their experience on how political decisions have shaped their community adds a deeper understanding of global issues, providing a unique opportunity for productive and critical debate. By discussing politics thoughtfully, students challenge assumptions, explore complex ideas and practice respectful disagreement. Politics may seem abstract until it is unpacked in conversations with peers.

Some argue that the classroom should remain an apolitical environment, out of fear of extreme bias or conflict. However, avoiding political discussions shields students from these biases, exposing them to unchallenged perspectives and limited assumptions. Silence becomes complicity, allowing political ignorance to thrive, leaving youth unprepared. As a result, reinforcing the idea that narrow visions of media, news and ignorance of other perspectives is an effective method to understand nuanced politics. In my view, such a mindset is highly detrimental and ultimately hinders a deeper understanding of the world’s complexities.

According to the Eurobarometer survey on youth participation in civic and democratic life, 73 percent of young people (ages 15-30) feel their education has prepared them with the digital skills to identify disinformation. Yet only 64 per cent of youth intend to vote. That gap reveals a troubling reality: students may be digitally literate, but more than a quarter of the European youth remain democratically disengaged. Either choosing not to vote or feeling ill-equipped to make informed political decisions. Classrooms have the power to reverse this trend, activating the inactive quarter, by making politics more present in education. As a result, guiding youth towards feeling empowered in their voice and political choices.

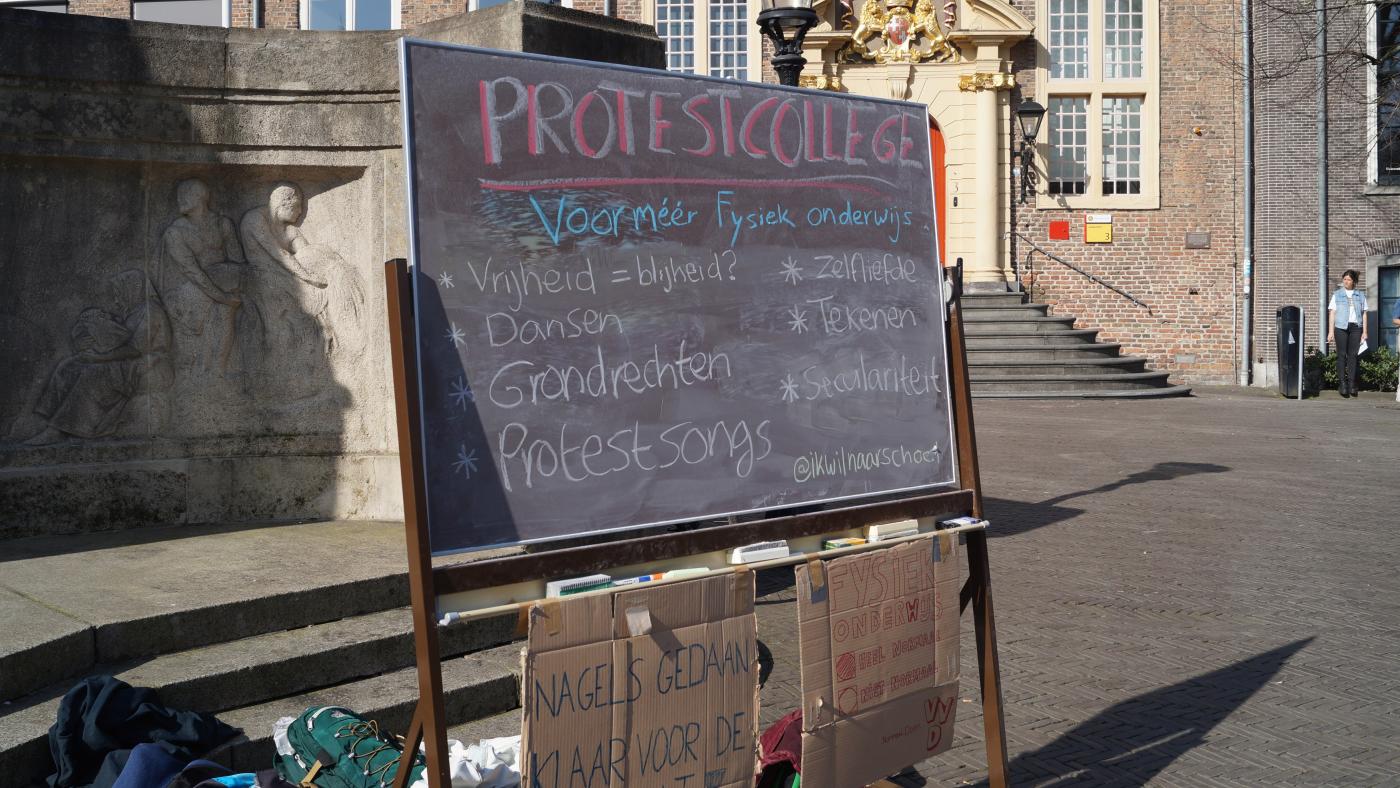

Blackboard during an outdoor discussion lecture during corona. Photo DUB

Political literacy is essential in today’s context of misinformation and media distortion. Classroom discussions under thoughtful guidance provide students with the tools to distinguish evidence from opinion, and catchy headlines from truth. Furthermore, students practice building and understanding arguments grounded in reason rather than reaction.

Additionally, we learn how to actively listen during civil discourse, challenging peers without undermining them. These skills are at the heart of creating democratic and reflective citizens. As Belgian political philosopher Chantal Mouffe argues, democratic politics is about shifting from antagonism into ‘agonism’, a respectful contest of ideas, moving from argument to civil dialogue. Despite this potential, many classrooms still fail to provide this conversational environment.

Educational systems often portray themselves as ‘neutral’, although they frequently reflect a dominant bias aligned with governmental narratives. These biases are conveyed through the perspectives and content taught in the classroom.

Students play a vital role in challenging these dominant narratives, urging educators to include diverse voices, perspectives and avenues for political engagement.

Furthermore, conversations that disrupt dominant narratives shape more critical and inclusive individuals, representative of the future. I expected more open dialogue at the university. Instead, I found many courses, educators and academic structures lacking the tools or willingness to engage in these critical dialogues. I am convinced that navigating tense or sensitive discussions is a fundamental part of educational responsibility, yet the fear of backlash leads to avoidance too often. While no conversation is perfect, creating institutional support for safe classrooms, passionate educators, and open-minded students is a crucial step towards shaping informed, thoughtful citizens.

We are often told that young people are the future. But the future does not begin after we graduate. Politics affects us now, and we deserve the opportunity to understand it now. We must be willing to confront difficult topics, not to win debates, but to build mutual understanding. When classrooms become spaces for honest dialogue, students grow into citizens who are prepared not just to inherit the world, but to improve it. Let us not shy away from politics in education. Let us embrace it as a shared responsibility of students, educators and institutions alike. Not as a battleground, but as a bridge toward empathy, critical thinking, and a better future for all.

This is an opnion article from Zoya Frumau, student Global Sustainability Science. The opinions expressed above belong to the author and do not necessarily represent DUB's views.