Being an academic and a politician means living in two different worlds

Can someone be an academic and a politician? At the same time? This discussion was raised when it emerged that science and politics had become entangled at the department of Encyclopaedia and Philosophy of Law at Leiden University. Politics and science mixed not only in the CVs of those involved, but in their scientific work, too.

Is that something to worry about? From an academic perspective, undoubtedly. After all, “Politics is statement above argument, academia is argument above statement”. For academia, it’s imperative that the two worlds are kept separate: “Never the twain shall meet”. From my own experience and reflection, there is a second position, however: “In life, you can be both academic and politician. But if you want to be both simultaneously, at the same place, you will be neither”.

The academically active politician

A personal confession: I am an academic who used to be a professional politician. I was just a passer-by in the seventies, but it remains an image-defining thing: “He’s a former politician…”. It can’t be denied, but it acts like a stigma. Once a politician, always a politician. Doesn’t sound like a compliment.

Nevertheless, there’s a kernel of truth here. For politicians, politics is a craft, and you can’t just unlearn a craft. Every day, you have to work on decisions that are both feasible and executable. That happens at every organisational level where policies are needed and feasible decisions need to be made. It happens in academia, too. There’s nothing wrong with that – on the contrary. Politics as a process within the university, by the way, is a different story: “the primate of the grapevine”. Not all that great. But that’s for another time.

So I became a politician and I was an academic in the same period. For six years, I was both. In the Dutch House of Representatives, I was the first spokesperson for the Politieke Partij Radikalen (Political Party Radicals), a party established in 1968, which merged with other left-wing parties to form GroenLinks (Green Left) in 1990. In that same period – from 1971 to 1977 – I was also part-time professor of Economic Development at the Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, an institution focused on Master’s programmes and special academic degrees. At the time, it was based in the Noordeinde Palace, just a five-minute walk from the Binnenhof (the seat of the Dutch government, ed.). Every Wednesday morning, I taught the course “Economics of rural development”. The classes focused on developing countries like Zambia, where I had spent four years working as a senior lecturer in Economics, associated with University of Lusaka.

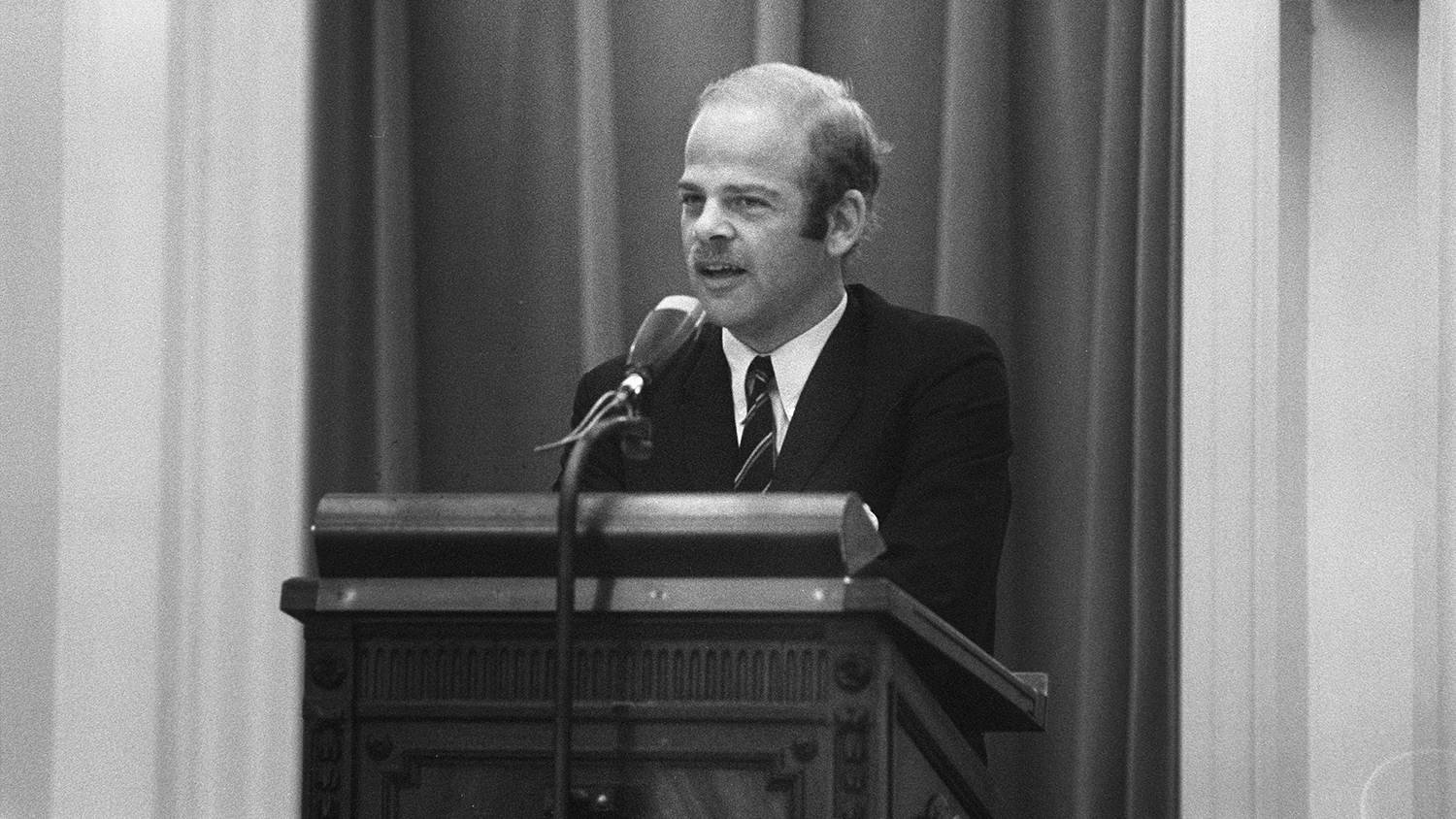

In the 1970s, Bas de Gaay Fortman was the leader of the PPR party in the Dutch House of Representatives. Photo: National Archives

The international environment at the ISS and the remaining connection with academia also had positive effects on me. I found refreshment at an academic oasis amidst a political desert. The academically-active politician.

The politically-active academic

The opposite happens, too: the politically-active academic. At Utrecht University, there was Ronald Plasterk, who at the start of this century served as chair of Developmental Genetics and, at the same time, published a weekly column in the Dutch newspaper Volkskrant in which his support for the PvdA party was clear. “That should be fine”, you may think, especially in this case, because his branch of science is not immediately connected to politics. But the question remains: where are your head and heart?

I remember his inaugural address (2001), an informal story of separate points that started with the announcement that this was his third inaugural address. At the time, professors had an informal meeting each month at the Kanunniken hall inside the Academiegebouw (Utrecht University Hall) near the Dom Tower. Recent events were told, followed by a lively discussion. The rector would often ask a question about a point on the Executive Board’s agenda, something they hadn’t agreed on yet. The colleague from Developmental Genetics was never seen in those meetings.

From the PvdA party, Plasterk moved on to professional politics in 2007, when he became Minister of Education. Soon after his appointment, he was invited to the inauguration of UU’s academic year, in which he delivered a powerful speech, great success. Some colleagues grumbled: he had never been seen at any of those events before. Just a matter of resentment? Possibly, but the point still stands. Academic and politician – is it possible to combine these two roles in one head and one heart?

Here, I have another thing to explain. In 1977, after six years of professional politics, I was appointed to the role of Professor of Political Economy at the Institute of Social Studies. In the same year, I became a member of the Senate representing the PPR party. Was that even doable? When I asked this question to the president of the Executive Board, I received the following response: ‘Our problem is the meagre output coming from the ivory tower where some members of our academic staff are stuck. It’s good if some of us remain in touch with the political and social reality”. In my case, that role applied to “the Netherlands and the poor countries” and the challenges of “development”.

The Senate

Moreover, I saw the Senate not in a political way, but rather in a professional way: as a test of the care and quality of the jurisdiction that had already been accepted by the Parliament. In the 80s, I was a member of the Justice committee, alongside UU Professor Martin Burkens, a sharp legal expert, who did not shy away from taking stands that didn’t please his party (the VVD) whenever he felt that was necessary. The Senate draws quite a number of professors, by the way. Jelle Zijlstra, Professor of Macroeconomics at VU University, started his contre coeur political career there, later becoming a minister and prime minister. He ended his career as president of the Dutch Bank, a position in which he found his place, his happiness. Today, there’s Annelien Bredenoord (Biomedical Ethics), who’s been serving as the leader of the D66 party in the Senate since 2019 – a key political position. A dual-role that fits her.

Seen from the side of politics, it’s important to have people who can – and are willing to – think about political issues based on academic knowledge and insights among the members of the Parliament, the provinces and the municipal councils. Still, the point remains about the academic mode that requires creative education and research. Neither academia nor politics benefits from a severely overworked colleague. These are separate worlds anyway, although one of the four pillars of the UU declaration of “societal impact” has bridged the gap.

The “Upper politics”

The situation is different for a professor of Politics who’s also a member of Senate, and who, from that position, negotiates the validity requirements for the implementation of a referendum. That doesn’t immediately mean that there’s a conflict of interest, but it does eliminate the distance an academic should keep in the assessment of the political process. Is such a legal design constitutional? If you’ve already answered that question at the Binnenhof, it’s hard to take it back in your position in academia.

That leaves us, finally, at the constitutional terrain. For national politics, the constitution is the normative framework to which the members of Parliament (House of Representatives and Senate), provincial states and municipal councils are tied through an oath or promise. What about academia?

That question arose in Utrecht in the matter concerning educational complaint in 2003. Since then, a rule is in place that states that UU follows the constitution in all its tasks (both educational and research and projects), with a primary emphasis on the commandment for equal treatment and the prohibition of discrimination declared by Article 1.

The meaning of the Constitution

Conclusion: academia stays far away from public politics – the politique politicienne as the French would say – but at the same time, it’s closely tied to “upper politics”. For now, there’s no reason to be too self-congratulatory. What’s being done to ensure that our community – administrators, employees, students – is aware of the foundation of Dutch democracy and constitutional state?

Sure, State Law organises an annual Article 1 Constitution lecture, but it’s not aimed at constitutional awareness among people outside the legal field. There should be an annual activity to do this, like the lecture named after professor Koningsberge, the initiator of the Utrecht protest against the persecution of the Jews, used to be.

Each department could also reflect on the meaning of the Constitution each year. Complicated? No. Think, for instance, about article 21: “It shall be the concern of the authorities to keep the country habitable and to protect and improve the environment”. East-Groningen, the climate crisis, energy conservation, sustainability, we could do so much with this!

Back to the place “somewhere behind Woerden”, as the University Leiden often has been called with a sense of ridicule. Politicians disguised as academics. But be careful: any attempt at Schadenfreude would bounce right back at us. Let’s start by ensuring that “upper politics” become part of general academic education.