‘Don’t stop at slavery, research UU’s entire colonial history’

With much interest, I read the report ‘Universiteit Utrecht en Slavernij’ (Utrecht University and Slavery, Ed) recently offered by an advisory committee led by James Kennedy to the Executive Board. The central question of the report is whether our university was connected to slavery and if so, how. How good that the university is investigating this!

Still, I call for an emphatic broadening of such a question to the colonial history of UU, its education and research, and the scientific development at our university. There is a history of underlying and structural inequality, and therefore also of slavery.

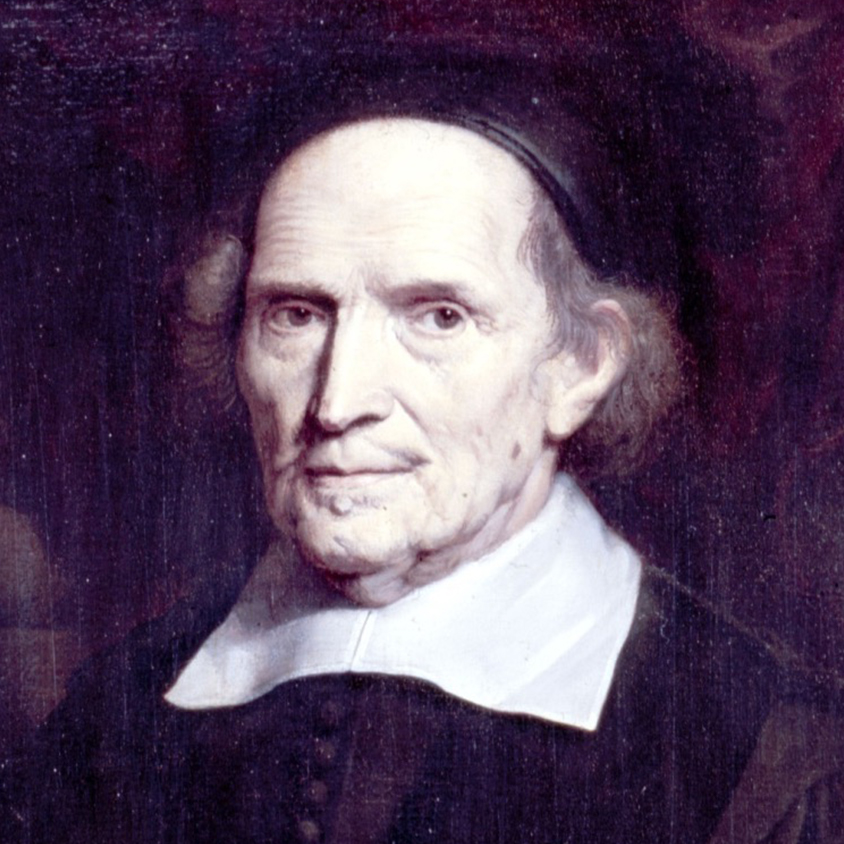

From Voetius to Oil

The university was founded in 1636 and, right from the start, it had a relationship with the "colony". Utrecht-taught preachers were sent to the so-called handelskerken, churches ministering to a mostly non-native merchant community, which were managed by the West India Company and the Dutch East India Company (VOC). These preachers, of course, took the theological theories of Voetius (1589-1676) and Hoornbeeck (1617-1666) to their new world. UU’s theology was the theology of reformed belief and the public reformed church.

This new world was also a world of people with different religions and languages, a world with flora and fauna that were previously unknown. And this new world was classified, collected, sketched, described and interpreted within our knowledge fields by people affiliated with Utrecht University, among others. This knowledge meant power!

With the growth of colonial society, mainly in the second half of the nineteenth century, this desire for exploration turned into exploitation and experimentation – which was so essential for the new natural sciences. Due to the Netherlands being a colonial power, several disciplines were able to develop during this period, especially the field of biology. Thanks to the inspiring leadership of F.A.F.C. Went (1863-1935), a Botany professor who worked at UU from 1896-1933, biology was able to develop as a modern experimental discipline mainly due to research in the colonies. The education of the "native" inhabitants only occurred occasionally.

The colonial history of the university is particularly highlighted in the Indological Faculty, inaugurated in 1925. People referred to it as the "Oil Faculty" or the "Sugar Faculty", since all the gentlemen grown rich in the oil and sugar trade financed the education of the administrative officers. The faculty’s "ideology" was very conservative: one of the professors openly wrote that "we" held the "authorship" of the colony, and were therefore entitled to its revenues! After all, "we" had brought civilization there.

After the Second World War, the "colony" became "a third-world" country and, after that, a "developing country". Utrecht, too, aided in the buildup of education and research in Africa, Asia and Latin America. At the time, they called it university development cooperation.

‘Brown-skinned with a fair soul’

In this colonial past, slavery was confronted time and time again. In 1676, Adrianus de Meij (… - 1699) studied theology in Utrecht. Adrianus was the son of a Dutch VOC official and a local woman in the then Paleacatte, Coromandel, on the southeast coast of India. After his studies in Utrecht, he went to Ceylon and became the rector of the so-called Malabaarsch seminary in Naloer in 1677. This seminar aimed to educate the local young men. The fortunate UU alumnus was a preacher, a seminary rector (he liked calling himself rector magnificus!) and… he owned over thirty enslaved people!

In 1669 Johan Basselier, UU alumnus and missionary in Surinam wrote: “to not only raise our Christian youth but also foreign and native darklings to walk in the light of justice while it is still above the borders of our horizon” or Sol Iustitiae illustra nos, the university’s latin motto.

Another example: Jan Willem Kals (1700-1781), also a theology student in Utrecht. He was sent out to Surinam, but because of his critical attitude to the whore-mongering displayed by the plantation owners and his explicit opposition to slavery, he got sent back to the Netherlands a few years later.

And then the example of Nicolaas Beets. Certainly, Beets, a poet, writer, preacher and professor in religious history and ethics from 1875, opposed slavery. He wrote the following in one of his poems:

Although we are black,

We have hearts,

As good as yours.

And should your hearts be better,

Then release ours from the pain.

Around 1750, William Juriaan Ondati (father of the well-known patriot Pieter Philip Juriaan Quint Ondaatje) and Hendrik Philipz studied theology in Utrecht. They were both from Ceylon. A newspaper article upon their return was full of praise: "both are from the Eastern Black Nation […] these brown-skinned but fair-souled easterners".

“Foreign and native darklings”, “Although we are black, we have a heart”, “brown-skinned but fair-souled easterners”! That brings me to the common thread throughout Utrecht’s colonial history. The university has constantly related to the Other, the not-yet-believer (of course, of "our" Christian faith), the not-yet-developed, through a strong Western-colonial sense of superiority. This has strong roots in the (Western) modernity that has a necessary counterpart in the coloniality of the Other. This sense of superiority and slavery are perilously close together!

Not Janskerkof 15 but Went building

I’ll formulate this more sharply. I’m slightly less interested in the history of a building at Janskerkof or the Drift that is currently used by the university and was once owned by a Utrecht-based magistrate who got some of his capital from a plantation than in, for instance, the Went building.

The Went building was located in the Utrecht Science Park, where the new RIVM building is now being built, and was named after famous botanist Went. At the end of the nineteenth century, Went played an important part in the colonial history of our university. It was Went who encouraged his students to go to the Dutch Indies as the possibilities for research there were numerous (“I see in my imagination Java, surrounded by a halo of sunshine, that offers its treasures to you, that beckons you, that calls for you to leave your foggy homeland to uphold the name of the Netherlands at the other side of the Equator!”). It was Went who propagated the idea of pure scientific research as a dimension of civilization in the Dutch Indies and Surinam. The application was meant for students from Wageningen! Indonesian students were only occasionally allowed to be involved in this science.

After the closure of the dentistry faculty, the Went building was home to the natural sciences such as biology and pharmacy, which have profited enormously off of the colonies. At the end of the nineteenth and the start of the twentieth century, there was a circular movement of Dutch academics, most of them from the hard sciences, trained in the Netherlands and at Dutch universities. These academics found a place to work in the colonies, they studied in research stations or took part in expeditions and extracted material (from humans too). Back in the Netherlands, they returned to the academic world and continued their academic career – scientifically enriched in and by the colony. Went asserted that "where the motherland was left behind (this included Utrecht University), the colonies became trailblazers". And with these experiments, the exploitation of the colony was strengthened!

I am advocating for a broad research program with an emphatic and systematic linking of the intellectual and colonial history of our university. That way, education and research, the raison d’être of each university, is put centre stage. Slavery will then become a logical part of the research into this past.

From colony to decolonization

Such insight into our colonial history will show us how we, as the university, should position ourselves in discussions about ‘decolonisation’. In other universities, in South Africa, for instance, this discussion has been going on for a while. At first, the anger there was focused on the external artefacts of colonial history, like the prominent statue of colonial pur sang Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town. But much more important is the critical approach to university education and research.

I have worked in university development cooperation for years. Certainly, I may have been one of the secular missionaries who came to people in Asia and Africa to show what a "real" university looked like and then offered help (developmental aid). "Decolonisation" means that, as a university, we have close ties to universities in other countries to which we now refer as "former colonies". We shouldn’t stop cooperating with Indonesian universities because China is much more important economically, like UU's Executive Board decided some decades ago!

Let's strive for true reciprocity. Don’t talk about "reparations", but rather establish a significant fund to help Dutch students obtain a doctorate, preferably in collaboration with students "over there", accumulate an extensive network of alumni in those countries, and have colleagues from former colonies ask you critical questions often: have we lost our colonial preoccupation, our traces of superiority?

Paul Kruger in our Academy building

The committee also suggested that we should look at the artefacts that remind us of our colonial history. I have a good example of how we can do this. In the times of heated debates about apartheid in South Africa, there was a beautiful statuette of Paul Kruger, the famous Boer leader, in an eye-catching place in the Senate hall, practically right beneath the portrait of the queen. The statuette was a gift from South African students, the Boer's sons, who had studied in Utrecht in large numbers. Mostly theology, because Utrecht still taught the orthodox teachings of Voetius.

The statuette was stolen by activist students for some time. It was eventually given back to the Executive Board, which quickly "hid" it away in the University Museum's depot. After the end of apartheid, the statuette was put back in a less prominent place in the Academy building, at the instigation of colleagues from the new South Africa. It now stands in a niche on the first floor, looking out at the Dom. Don’t hide the past away in a museum!

Henk van Rinsum worked in the department of research support and was a board secretary at the Faculty of Humanities until September 1, 2019. Before that, he was responsible for university development cooperation for years, among other things. Van Rinsum previously published ‘Sol Iustitae en de Kaap’, a book about the history of UU's relations with South Africa. He is currently working on a publication about UU's colonial history. Van Rinsum is connected to the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa as a research fellow.

Photo credits: the pictures of Nicolaas Beets and Voetius were taken from the University Museum collection; The picture of the Paul Kruger statuette is courtesy of Henk van Rinsum; The photo of Friedrich Went comes from Wikipedia; The picture of the Went building was taken from DUB's archive.