Age-old hazing rituals have always been controversial

The first time a tradition of hazing newcomers is mentioned comes at the end of the eighteenth century. The older students felt superior, and taunted the younger ones from clubs who’d started to call themselves senate. In that time, students were still taught in the homes of the professors. The course material a professor gave would take more than a year. Students could enroll at different times during the year, and so younger and older students often had class together.

In 1793, the Senatus Veteranorum Glirium (‘the Senate of the Old Rats’) was founded in Utrecht. It wasn’t just the newcomers who were given a hard time. The senate also wanted to ‘contrary, hinder and disadvantage’ others, ‘both in public and in secret’, including ‘professors, parents, governors, teachers, landlords and other students’.

The new students let the hazing wash over them, because the young ones wouldn’t have been accepted as full students without the acknowledgment of the hazing senate. The hazing in those first years was a rather tough-love approach to introducing them to student life. The freshmen had to greet the elder ones following specific protocol, were not allowed to wear swords or play billiards, and were not allowed to use profanity.

The rules and habits of the hazing senate were a parody on university. Existing university rituals were imitated and ridiculed. Newcomers had to take an exam, with as a result, a diploma and a beret. They were allowed to call themselves doctor. Latin was the main language used, and the ceremony was ended with a party paid for by the younger students.

Officially, it wasn’t a social association, but the senate did have its own housing at the Domplein. In 1816 it officially became an association with its own housing called Placet hic Requiescere Musis (PhRM), which means: It pleases the Muses to rest here. This happening is seen as the founding of the Utrechtsch Studenten Corps (Utrecht Student Corps). The Corps wanted to not just haze the students, but also guide them and prepare them for life as adults.

Even then, hazing was seen as a problem, according to the first chapter of the book, which paints a picture of student life in Utrecht between 1636 and 1945. Around 10 percent refused to let themselves be hazed. In 1839, a student in Utrecht wrote a plea for ‘an improved hazing’. He says the first-year students shouldn’t be insulted and mistreated in the presence of civilians or in public places, that hazing should only happen outside of the classroom, and that unwanted touching and ‘non-noble behaviour’ should be prohibited.

For a long time, the Utrechtsch Studenten Corps was the only student association. Every student was more or less automatically a member, and the student corps (as counterbalance to the teacher corps) acted as the way to contact students for the university. The association organised the lustrum games in name of the university, with a masquerade once every five years, starting in 1836. In 1848, the university had 25 professors and 400 students. Studying was expensive, and therefore exclusively available to the elite.

That changed in 1863, when not only pupils from a Latin School (gymnasium) could apply to university, but pupils from the Hogere Burgerschool or hbs as well. The number of students grew, as did the diversity. The consequence was that not everyone became a member anymore. Especially the middle class students couldn’t always afford the USC’s membership fees. Additionally, the resistance against hazing increased. New members’ heads were shaved as a sign of subordination to the lavishly dressed elder corps members. Those who weren’t members were called nihilists.

As a counterbalance to the corps, the Utrechtse Studenten Bond (Utrecht Student Union) was founded in 1884, with values such as equality, lower fees, and a distinct lack of hazing rituals. This union didn’t last long. After only a year, the union was forced by the university to merge with the USC. The Hague threatened to close the university for, among other reasons, ‘that breeding ground of discord amongst students’, said member of Parliament Kees Schaepman.

The merger was not a success. In 1890, the Utrechtsche Studentenbond (Utrecht Student Union) was founded, which in 1911 merged to form the association Unitas Studisorum Rheno Trajectina. The association was open ‘to everyone’ and distanced itself from hazing rituals. In this period, more associations were founded, such as the catholic association Veritas (1889), women’s association UVSV (1899) and the protestant Unie der Societas Studiosorum Reformatorum SSR (1906). Life in associations was the ultimate place for students to engage in sports and cultural activities. That way, many sub-associations were formed.

Society-wide, however, an aversion against hazing grew. In 1913, the national Vereeniging tot Bestrijding van het Groenwezen (Association for the Eradication of Hazing) was founded. The USC lost its status as contact point for all students bit by bit. Un until then, the USC also had study clubs in each faculty, which acted as the contact point for the academic faculties. Other associations started to do the same, which led to an actual ‘matter of faculties’. In 1939, the study program faculties were separated from the association, and after the war, the Utrechtse Studenten Faculteiten (Utrecht Students Faculties, or USF) was founded, of which for a very long time afterwards, the president of the USC was automatically chairman. That way, the difference between social associations and advocacy associations slowly grew.

In 1950, half of all students were members of a social association. Halfway through the 1960s, that number fell sharply due to a renewed clash between the traditional social associations and the increasingly impetuous society. The associations were more and more seen as right-wing, and the hazing ritual as authoritarian.

The number of students at university also increased, which meant more and more of them were first-generation students, whose parents didn’t have an academic background. There were students who joined an association just for the sports or cultural activities. This trend unermined the traditional association bond, according to the USC board at the time. That led to a harsher hazing period – the harsher the hazing, the tighter the bond, they reasoned.

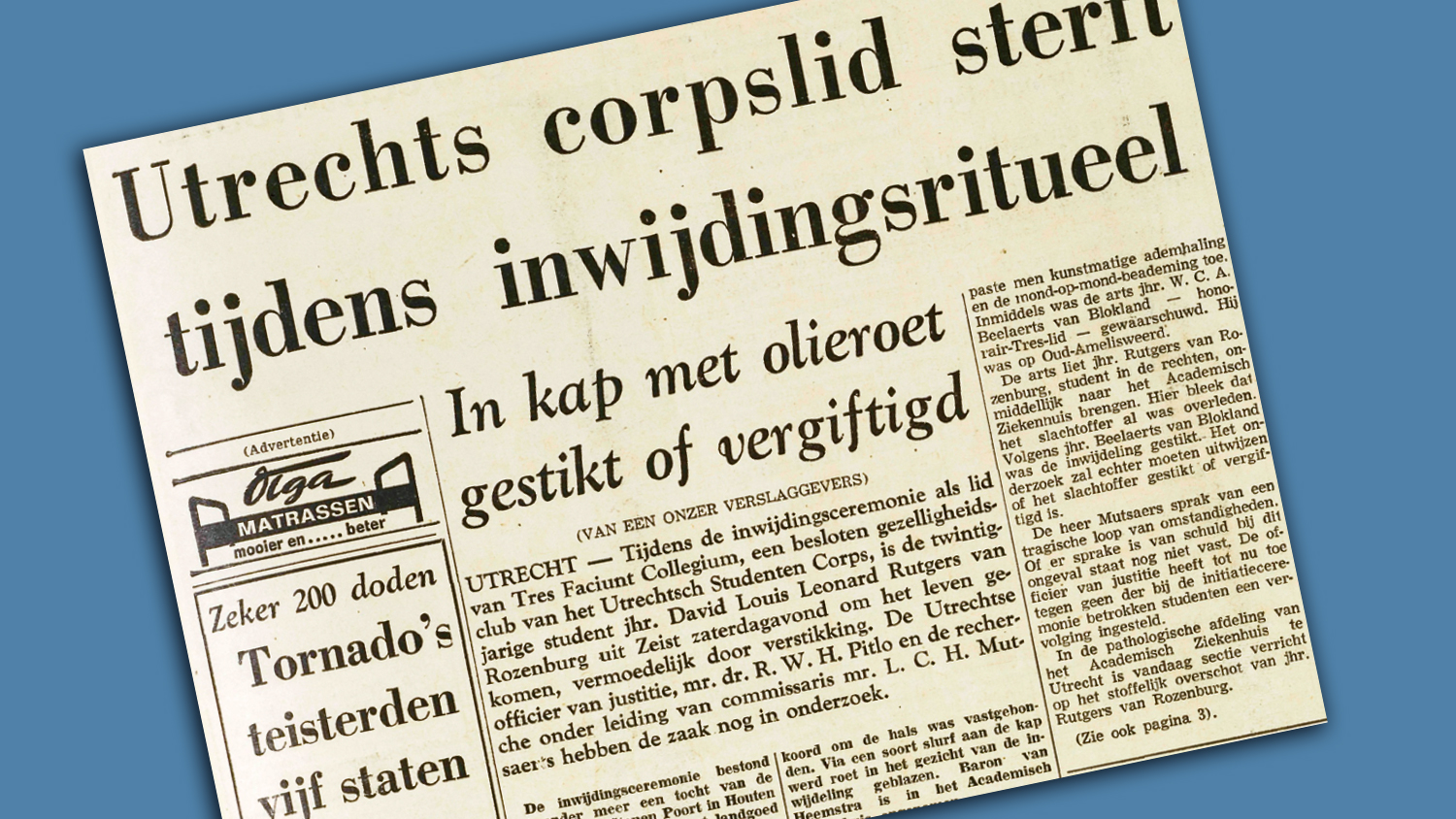

The opposite happened. The excesses led to more opposition against the corps’ frat behaviour. The USC made the national news in 1965, with its so-called Roetkapaffaire, when a student choked to death after wearing a soot mask (‘roetkap’) during a hazing ritual. More and more members left the association.

In 1969, this development led to a heated discussion among USC members about the severity of the hazing rituals. A small majority eventually chose to continue the tradition of shaving heads – only to finally be abolished a year later anyway. Within the confines of the association, discussion ran rampant. Critical members wrote in the association’s magazine Vox that the rigidity caused ‘a mightily flourishing, rich, valuable students’ association to ruin itself completely within only a few years, due to a lack of understanding and mismanagement.’ Membership numbers plummeted. Other associations likewise saw their numbers decrease. Out of all of them, Veritas managed the best to stay afloat, thanks to its left-wing catholic character. SSR wanted to become an open youths association, which led to a division, named Biton (Ben Ik Terecht Of Niet, loosely translated to ‘Am I right or not’) and SSR-NU.

At the end of the 1980s, the associations managed to regroup. The associations adapted, and the revolutionary spirit slowly faded from society. Many sub-associations continued independently, both in sports and in cultural activities.

The past few years, increasing workloads for students make the social associations less attractive to students. Students prefer to first make it through their first year (and get the attached ‘bindend studieadvies’, or ‘binding study advice’) and only then join an association. At the moment, only 10 percent of all students are members of study associations. This is due in part to the increase in sports associations, study associations and cultural associations. It also begs the question of whether students even have the time to be active in a committee, or spend a year on a board.

The discussion about hazing was always present in the background. In 2002, both Veritas and Unitas were hit with sanctions due to excesses during hazing rituals. In 2016, Veritas was once again reprimanded by the university due to ‘Guantanamo Bay-like practices’. This winter, UVSV faced heavy criticism after a TV show called Rambam aired. The images that were broadcast were later judged to be ‘ugly’, but the association hadn’t violated the code of conduct that the university had agreed upon with the associations. This code of conduct is meant to ensure ‘an introduction period without humiliation and physical violence’. It isn’t always successful. Groningen and Amsterdam continuously end up in the news in a negative light. Throughout society, people are wondering more and more about the use and necessity of hazing rituals, even if they’re explicitly not named as such nowadays.

Still, the FUG (Federatie Utrechtse Gezelligheidsverenigingen, or the Federation of Social Associations in Utrecht) doesn’t want to hear a thing about a switch to a possibly less student-like character for these associations, according to chairman Marc Oosterhuis. He thinks the social associations could stay afloat by offering association houses, workplaces at their own buildings, and letting members gain experience on the job market. He’s also calling for increased social engagement of all associations.

This article was based on chapters 1 (Student life 1636-1945), 7 (Happy non-commitment and usefulness) and 8 (Against injustice and oppression) of the book De Utrechtse Student 1945 tot nu (The Student in Utrecht 1945 to now), edited by Leen Dorsman, Hylke Faber and Pier Stolk.

Translation: Indra Spronk