DUB joins the Technical Inspections team

Broken clocks and power strips bought at Action: 'this could go terribly wrong'

It is perhaps the most chaotic desk of the entire laboratory, located on the eighth floor of the Hugo R. Kruyt building at the Utrecht Science Park. A jungle of power cables leads to a number of different devices. As a philosophy student, their workings elude me.

Assayer Roel Zwitselaar is looking for his "approved" stickers, while his colleague Christiaan Veenman tries to poke the metal rod of his measuring instrument through the layer of white paint on a freezer. “I can only do my measurements when the rod touches metal. Paint doesn't work,” he explains.

For several weeks, the duo has been inspecting every electrical device with a plug in the Hugo R. Kruyt building, computers excluded. Today, we are on the eighth floor, where we will check every device for lack of safety, from sandwich toasters to infrared lasers.

There are four other assayers: Mielke Sarkol, Martin Dalemans, Richard Missler and André Pasker. They visit the university's buildings in groups. According to the Working Conditions Act, devices must be inspected every three years so that students and staff are able to work in places where the risk of electrocution or fire is negligible. Fons den Exter Blokland who takes care for the administrative support, completes the team.

Accessible

The team was put together in April 2022. Before that, the inspection used was mostly outsourced to the devices’ suppliers, explains the coordinator Lidwien Graafland, but that system became untenable. At the Exact Sciences Faculty, employees of the Instrumentation team were handling the inspections themselves but they lacked the capacity to do the same university-wide. That's why the Technical Inspections team was created.

In the past, the inspection days caused a few disruptions, which meant that inspections often had to be completed as quickly as possible and the devices had to be gathered in a single place beforehand. As a result, employees had to stop working for a while.

“We are much more flexible now,” Christiaan says. “Since we are working on this year-round, it is no trouble for us to come back later if a certain device has to be used all day. We’re much more accessible now.”

Roel has been working for UU since 1980. He started at the pharmacy of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, working as a building manager for a long time. “You could say I was the jack-of-all-trades of facility services. If a lecture hall had to be emptied, I was the one who would drag out the furniture.” Due to his years of experience, he knows many of UU's buildings like the back of his hand, which comes in handy in his current role.

Christiaan has completely different origins. He used to work at the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Dutch acronym: RIVM), where he spent years conducting research into bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. He then worked briefly as a researcher at Wageningen University & Research but his team was not so enthusiastic, which led him to look for a different place to work. For him, too, his previous experiences come in handy in the laboratory: Christiaan recognizes many of its devices.

Asked whether he misses research at all, he states: “A little bit. They are doing fascinating research here. But it's nice to talk to the scientists about that.”

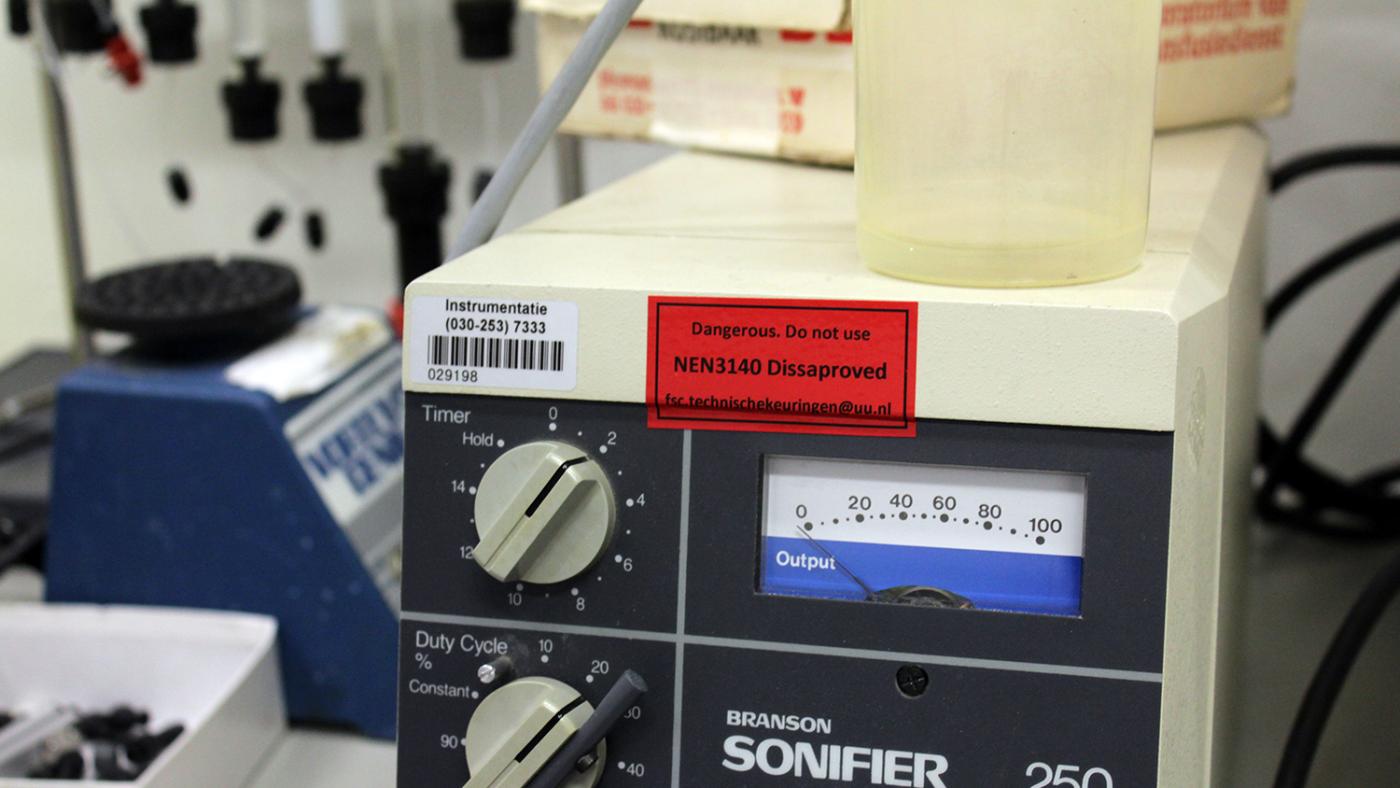

Rejected. Dangerous. Do not use.

I notice that my presence slows down their work a little bit. We’ve been gathering around the second device for fifteen minutes. It's a "vortex mixer", an instrument to mix the contents of test tubes. The assayers look at the condition of the cords, check whether there is any current leakage, and verify the quality of the grounding. “Otherwise, the power doesn’t flow towards the earth but rather towards the user. That wouldn’t feel good,” Christiaan explains.

They also take a good look at all the power strips. It is not unusual for things to go on there. “Look, a power strip bought at Action, among all that expensive equipment,” Roel points out to me.

It is still pretty common for far too many devices to be connected to a power strip that lacks the capacity to handle all that. Sometimes, power strips are even connected to each other, which can be a fire hazard. “That’s really not allowed,” Roel tells me.

When a device does not meet the requirements, the assayers affix a yellow sticker on it which reads, ominously: "Disapproved. Dangerous. Do not use." The assayers then notify a building liaison about which devices should be moved to the waste disposal. That person must arrange the actual discarding themselves.

The assayers estimate that about a tenth of the devices are rejected, but they aren’t sure. “Many of these rejected devices are power strips that pose a fire hazard, for example. But we see many risky cases, such as cords that have been repaired with duct tape,” Roel says.

Among all the complicated devices, we come across an ordinary clock that is almost falling apart. The once-white face now has a dirty yellow colour, the steel housing is reddish-brown from rust.

“Ugh, look,” Christiaan says. “What kind of clock has a plug nowadays? Surely that would work much better on batteries?” The cable sheath is also almost completely gone, two thin power wires barely hold the cord together. Such an exposed wire can cause the entire steel housing to become electrified and is very dangerous. After some fiddling with the sticker sheet (“quite difficult with rubber gloves”), the clock is finally rejected.

Most devices fare far better, by the way, with a reassuring ‘Approved according to NEN 3140’-sticker.

Yellow power strips

While I am following the assayers on their lab rounds, I suddenly see plugs and devices everywhere. “In a lab like this, there are sometimes as many as two thousand devices. In theory, this lab could take us months to inspect.”

The experienced assayers now know how to best check most devices but sometimes it can still be a bit of a mess. “Cable ducts under desks are particularly terrible. We have to crawl.”

The biggest annoyance, according to them, is the quality of the power strips. At the moment, UU employees tend to just arrange for a new one themselves when needed but they hardly ever consider safety. According to the assayers, this has to change.

The team already has a plan to solve this problem, Roel states. “We are now looking at the possibility of centralising the purchase of power strips. Then we will only have high-quality power strips at UU. Yellow-coloured, for example. I know the university prefers to spend its resources on research but this sort of thing is also extremely important.”

Awareness

“This team is a great project,” coordinator Lidwien says. “Our work methods are still evolving all the time, which I find fascinating.” Christiaan gives an example: “In the past, we measured the devices’ response to peak voltage in the laboratories. Sometimes, that inspection caused a device to break, which is why we now have a new system.”

Moreover, the assayers will soon do a training course so that they can immediately repair devices themselves. That will prevent annoyances such as the device being unusable for a while, for example.

The assayers and Lidwien think the most important thing is for UU employees to know that the team exists and what they do, which is why they are planning on sharing online information with UU employees about the safe use of electrical work equipment. Sometimes UU staff is annoyed at the team because they do not know why they do what they do and why they reject certain devices.

The building liaison’s attitudes reflect this. “They react very differently when we tell them that certain devices have been rejected. Some are grateful but others are like 'that's nonsense. Why are you interfering? Those devices still work'. That's a shame because we don't do it for nothing,” Christiaan laments.

However, the vibe in the team is good and most UU colleagues respond positively to them. After all, the assayers work to ensure their safety. "The other day I saw a girl making a toasted sandwich with a device whose cord had melted away to the copper wire, on a steel table of all places. Something like that can go horribly wrong,” Roel recalls. “I told her that and, when I returned the next day, the toaster was gone, thankfully. That makes me feel good.”