Three UU scientists on behavioural change

Do individual actions help combat global warming?

Utrecht University's theme for the year is ‘healthy planet’. This means that extra attention is being paid to sustainability, health and climate change. The extent to which this has a positive effect on staff and students has not been measured, but research by Ipsos, which was reported on in an article in the Dutch daily newspaper De Volkskrant, shows that young people in the Netherlands feel less urgency about the climate problem than before, and that their CO2 emissions have increased compared to last year. DUB regularly hears that this frustrates those who have changed their behaviour. And that can be demotivating. So does it still make sense to give up meat and stop flying?

First there is a change in attitude, and only much later does behavioural change followg

A minority can certainly bring about a social tipping point, says Madelijn Strick. She is an associate professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences and conducts research into social influence, communication and behavioural change. She also recognises the concerns of students. “People want to improve their behaviour, but they see that no one else is doing the same. Then you start to wonder how much sense it actually makes.” However, she believes that not all change is immediately visible. “There is much more going on mentally than you see on the surface. Even people who still eat a lot of meat often want to cut down.”

According to Strick, social change often happens in phases: “First there is a change in attitude, and only much later does behavioural change follow.” She emphasises that being honest about the fact that you find it difficult to change your behaviour can actually encourage others to join you. “Take eating meat, for example. People often think: ‘I'll only share my intention once I've actually stopped next year’. But it's important to share at an early stage. It's inspiring to hear that someone is making an effort to change, and if they don't always succeed, that makes them more human. Then you can look for solutions with your friends and even influence their behaviour.”

It sounds almost too good to be true: tell your friends that you're trying to stop eating meat, and they'll give up hamburgers too. But is that enough to create a tipping point? Strick: “I would also like to see the government take bigger steps to rein in the industry, but they too are responding to social changes. Whichever way you look at it, you have to organise together if you want to get something done. And to do that, it helps to be open about your own moral considerations.”

According to her, consumers also have more influence than they often think. "Because people have been booking fewer flights to America lately, you see that the number of flights on offer is decreasing. Supply follows demand. Political parties also constantly take the consumer behaviour of their voters into account.

Playing is a very good way to learn something because it is a source of pleasure

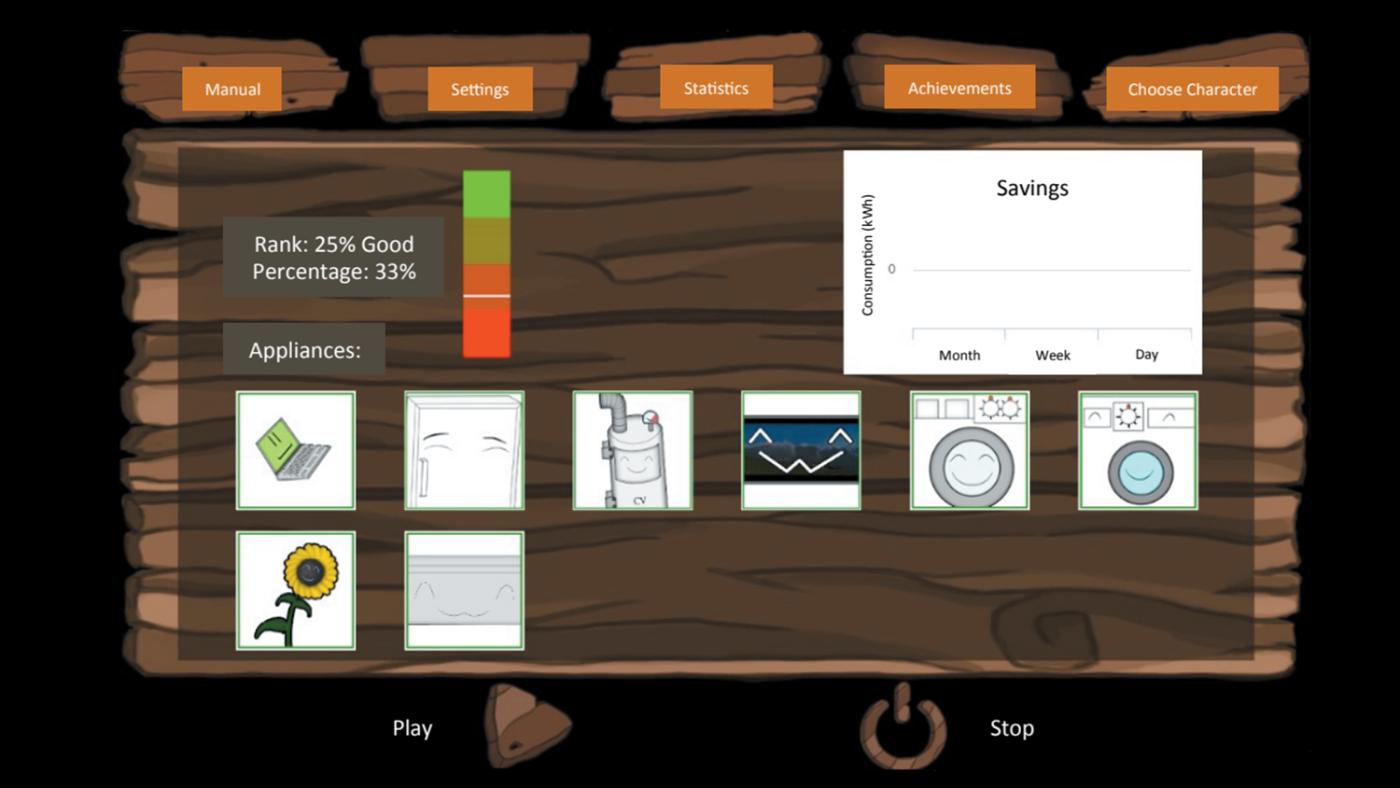

Power Saver game of Jan Dirk Fijnheer

Someone who actively tries to teach people to adopt a more sustainable attitude is Jan Dirk Fijnheer. For his PhD research, he developed the Powersaver Game, a game that helps households save energy.

It works as follows: each household receives daily tasks for a month, such as washing at 30 degrees or closing doors between rooms. You progress in the game based on your energy savings, which are measured by a smart meter in your home.

The results are impressive: households that play the Powersaver Game consume an average of 30 percent less energy than households that only use an energy app. Fijnheer explains why this form of ‘gamification’ is so effective for behavioural change: "Playing is a very good way to learn something because it is a source of pleasure. Just look at children or animals.

What's more, it takes an average of 21 to 60 days for new behaviour to really stick. People who only have an energy app often give up sooner. The Powersaver Game is fun, which keeps you motivated to keep going."

In addition, behavioural change often requires giving up comfort, which people find difficult. The game element makes that easier. According to Fijnheer, we are also better at adapting than we think: “A hundred years ago, households heated their homes with a single small stove. So whether the thermostat is set to 20 or 18 degrees, it's just a matter of what you're used to. We often say that we are ‘saving’ energy, but you could also say that we are simply wasting less.”

With the help of a tool such as the Powersaver Game, even a minority can have an impact. Fijnheer cites the example of grid congestion, which can be solved if people consume less energy: “If only 15 per cent of households in a neighbourhood play the Powersaver Game and save energy as a result, that problem can be solved.” Fijnheer is not in favour of mandatory measures: “There has to be intrinsic motivation. Technical solutions are valuable, but ultimately behaviour has to change too.”

If you really want to change something, you can just google how best to do it

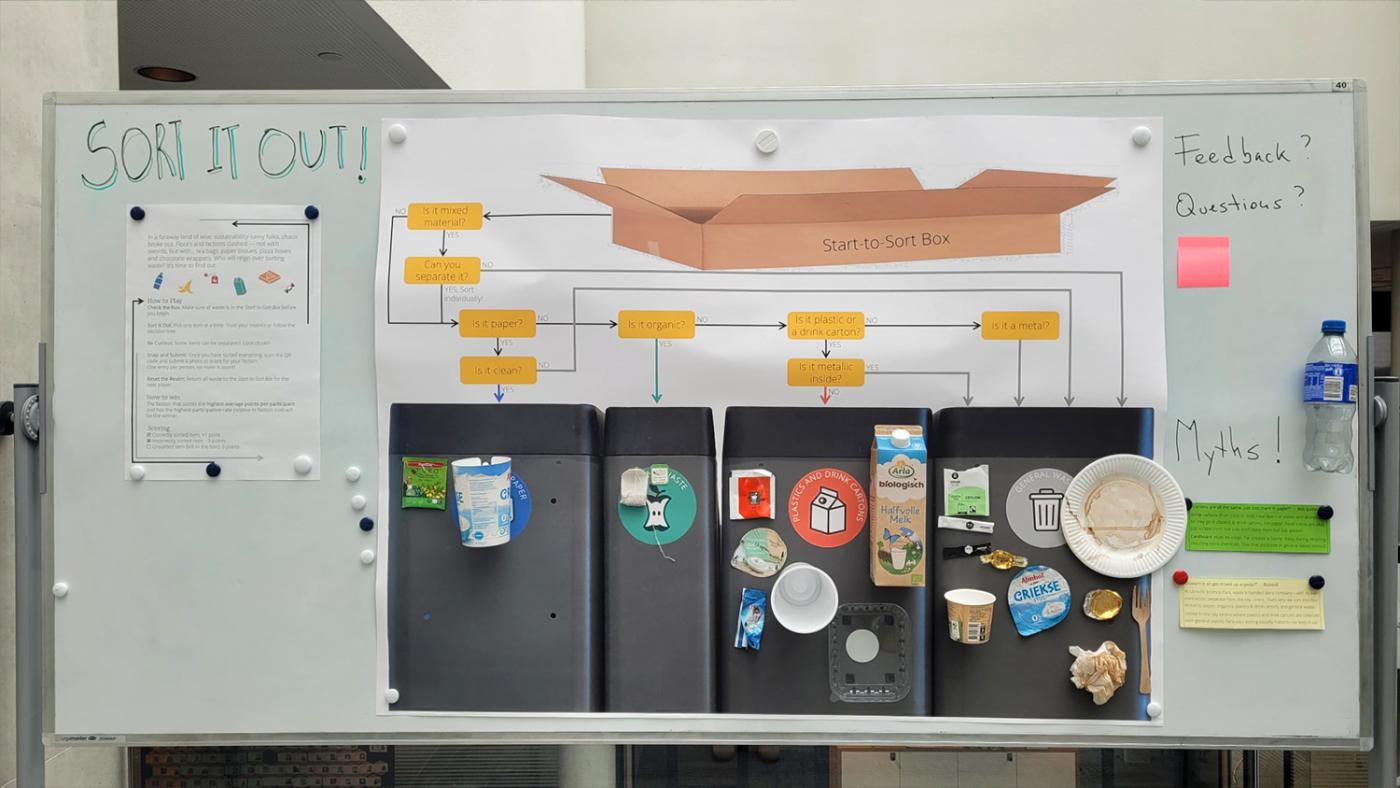

Sort it out! Game of Claudia Stuckrath Alvarado

Claudia Stuckrath Alvarado is involved in sustainability. She once worked as an civil engineer in Chile, where she collaborated on the architectural design of coal-fired power stations. But she gradually began to doubt the meaning of her work. “One day I left the jobsite with coal coming out of my ears. Then I knew, this has to change”

She decided to change course and started a master's degree in Sustainable Business & Innovation at Utrecht University. “I am not an activist, but an engineer so I believe in practical solutions.”

She is now a PhD candidate at the Copernicus Institute and is involved in the Centre for Living Labs, environments in which innovative solutions to societal challenges are developed and tested. Although she works on projects that take her all over the university, she discovered something remarkable close to her own workplace.

“When I first started out here, I noticed waste not being sorted properly in the bins outside of my office. Not once in a while, but structurally.” Together with her supervisor, she investigated. “We discovered that 50 percent of the waste was being disposed of incorrectly.” Ironically, this is happening in the Circular Economy department of the Copernicus Institute. If anyone should know how important recycling is, it's them, she says. ‘But if even they're not doing it right, how can we expect others to do it?’

According to Alvarado, a minority can cause not only a positive but also a negative tipping point. She explains that waste processors manually check whether waste has been separated correctly. If too much waste ends up in the wrong bin, the entire batch is incinerated and everyone's efforts have been in vain.

To combat this, she came up with a game: different departments had to sort fake waste and send her a photo to score points. “That has started interesting conversations about the whole problem around waste generation.” According to her, the problem lies in the complexity of the recycling system. “In the Netherlands, every institution has a different company that processes its waste. Even the University of Applied Sciences and our university at the Science Park work with different parties, each with their own rules. That's confusing.”

Nevertheless, she does not believe that a lack of knowledge is the biggest obstacle to sustainable behaviour. "If you really want to change something, you can just Google how to go about it. The problem is more that people don't think it's important or that they see that others aren't doing it either.” She noticed this strongly after arriving in the Netherlands: “In Chile, we eat a lot of meat. I do that much less now because of peer pressure and because there are more alternatives here." Nevertheless, she is cautious when it comes to enforcing sustainable behaviour. “You have to be careful that it doesn't encroach too much on people's private lives. I've never owned a car, but I've always been lucky to live close to work. That's different if your partner works further away.”

This is the third article of a series taking a deep dive into climate change and who is responsible for combatting it. DUB readers were invited to choose among three topics they would like to read more about. Most readers wanted to know what individuals can do to save the planet. They wonder how much individuals should be made responsible for climate change, to what extent measures can be imposed, and what role governments or universities play in the fight against climate change.

You can find all the other articles here.