Former Ublad employee Martijn van Calmthout writes biography about Nobel Prize winner Gerard ‘t Hooft

‘Gerard is very funny, but in a really understated way’

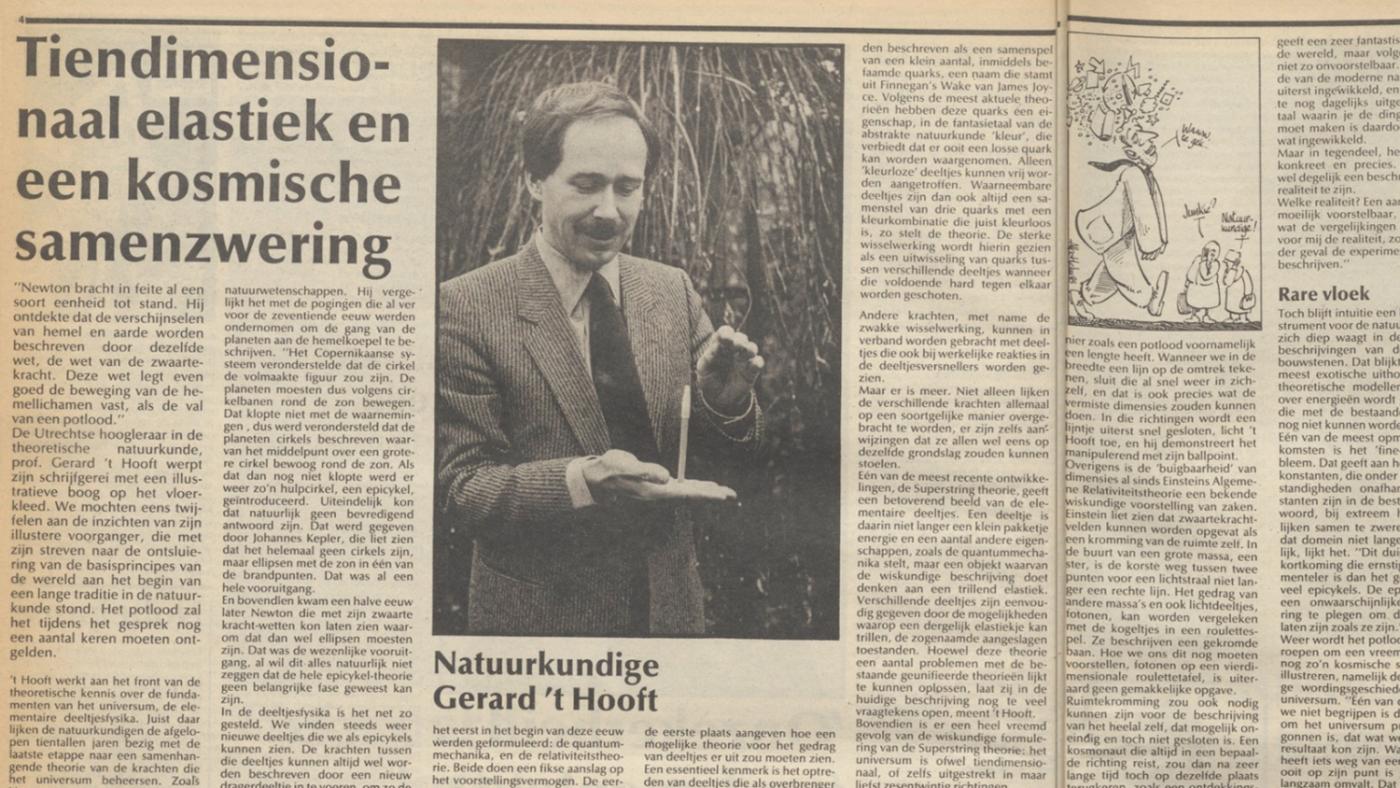

If you browse through old Ublad editions on the website of the University Library, you will find a long conversation about elementary particles with the theoretical physicist Gerard ‘t Hooft. It's in the December 20, 1985 issue (page 390, 17th volume, Ed.). Its authors are the editors Erik Hardeman and Martijn van Calmthout. The latter remembers that conversation quite well. It took place in ‘t Hooft’s office at Princetonplein. “I studied physics in Utrecht myself, though not with ‘t Hooft, but I knew what theoretical physics were about. Yet, during that conversation, Gerard occasionally said things that I couldn’t understand because he has a level of abstraction that you can’t reach even with a reasonable amount of knowledge of physics. He always does his best to explain things but there are always details that trip you up. It's particularly hard when you have to write about it in a magazine. Nevertheless, I was fascinated by what he said.”

Martijn van Calmthout and Erik Hardeman interview the physicist Gerard 't Hooft. UBlad, 1985

After graduating from university, Van Calmthout quickly realised that a career in science was not for him, so he started working at Ublad. “I found what was happening in particle physics insanely fascinating, but I didn’t feel as though I could make a useful contribution to it myself. What appealed to me the most was communicating about science.” After a few years working at Ublad, he moved to the newspaper De Volkskrant, where he was one of its science editors. Thanks to this job, he talked to ‘t Hooft frequently. “I spoke with him a few times a year, sometimes for an interview but mostly to ask him to explain things over the phone. Some form of understanding was created between us because of that. I wouldn’t call it friendship but I could tell he trusted me.”

Van 't Hooft ahead of the launch of his biography. Photo: Pieter van Dorp van Vliet

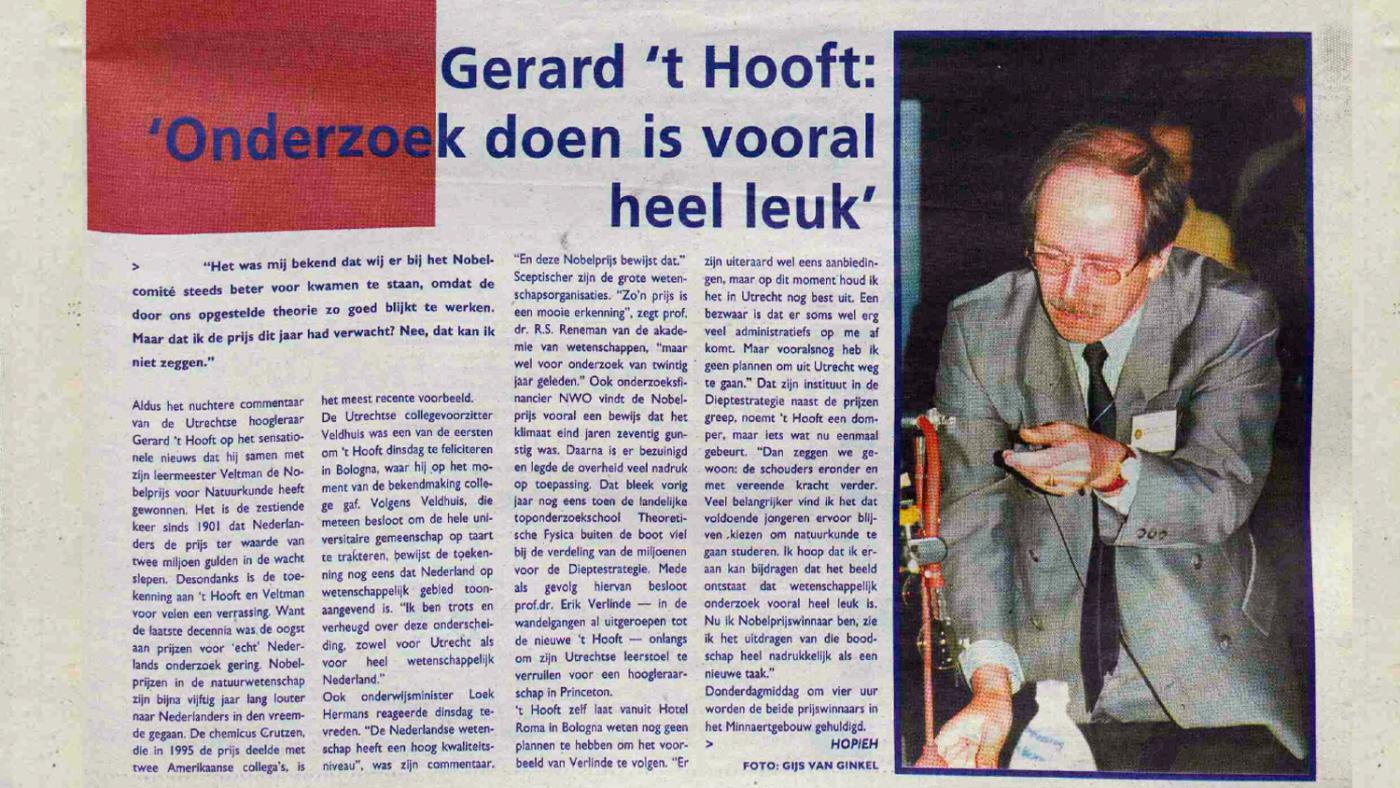

This became clear in October 1999, when ‘t Hooft won the Nobel Prize alongside his mentor Martinus Veltman. “De Volkskrant obviously wanted to interview him first but he was in Bologna at the time, so it wasn’t easy. Just getting him on the phone was quite a feat but, when we finally did, he said he was expecting to be so busy that he wouldn't have time for an interview. So, I replied: 'If I go to Bologna and fly back with you to the Netherlands, we will be able to talk for an hour and a half, and then I will stop bothering you.” Van Calmthout laughs. “Well, if you work at a newspaper like De Volkskrant, you must have a certain amount of journalistic boldness. Gerard was surprised by my proposition but he ended up agreeing that an interview during the flight was a good idea (link in Dutch, Ed.). I then flew to Bologna and waited for him at the gate. I still had to figure out how to sit next to him on the plane because we had booked our tickets separately, though, so we started shuffling people around on the spot. And he helped me do it. That’s just how he is.”

Nobel prize winner Gerard 't Hooft on Ublad. October, 1999

Not dead yet

Getting the Nobel Prize made it even more clear to Van Calmthout how important ‘t Hooft had been and still was for theoretical physics. “I thought it was strange that there was no biography about such a prominent Dutch scientist, especially after the Nobel Prize. It was high time for one. So, I thought: why not write it myself? I asked him to do it several times over the following years but he always answered: 'I’m not dead yet, am I?' Besides, he was afraid that it would be a boring book. 'I’m not an interesting person at all. Who wants to know so much about me?’”

Van Calmthout kept insisting and noticed that ‘t Hooft gradually started to open up to the idea. “When he finally said yes, at the beginning of 2020, my first thought was: ‘Great, I did it!' but my second thought was: ‘Oh my God’. I suddenly realised that, even though I had often written about Gerard’s work, I had never really understood it properly, at least not as I understand it now. I am certainly not dissatisfied with my newspaper articles because I think I've covered his work quite well considering that a journalist never really gets enough time to write. But now the situation was different. This was going to be a book about him so, in order to write that, I really had to understand what he had done. I had to go back to studying physics.”

't Hooft alongside Martinus Veltman, with whom he shares a Nobel Prize. Photo: Maarten Hartman, Ublad

Biltstraat

Van Calmthout also wondered how he could write a biography about someone who is still alive. “I decided to have conversations with Gerard because I wanted to hear his story, his observations and reflections about certain events. He could consult his archive if he didn't remember something, as I couldn’t access it myself. It was perhaps a disadvantage that he could decide what to tell me and what to hide from me, but he was very candid and it was nice to hear firsthand how things had gone. I got information about events that I probably would have never found out about in any other way.

“Our agreement was that I could use everything he said. However, it's inevitable to come across subjects that he would rather not see in the book. We've had a few discussions about this, especially regarding the somewhat difficult relationship he had with his mentor, fellow Nobel Prize winner Martinus Veltman. That was a tricky part of the story. I knew a lot about it because I had written about it in the newspaper but Gerard didn’t want to say much about the topic. He understood that it couldn’t go unmentioned but he didn’t want to stir things up again.” Earlier this year, a biography of Martinus Veltman, written by Dirk van Delft, was published under the title Verrek dat is het (Damn, That's It, Ed.). This book addresses the difficult relationship between Veltman and ‘t Hooft as well.

What made their relationship complicated was an argument regarding whom the breakthrough that earned them both the Nobel Prize in 1999 should be attributed to. The breakthrough came when 't Hooft published an article in 1971, proposing a solution to a tough problem in particle Physics. Veltman was once walking on Biltsraat, wondering aloud how that problem could ever be solved, when Gerard said, to his astonishment: ‘But I can do that.’ (Maar dat kan ik, the title of the biography being launched now). Van Calmthout: “That's the title of my book for a reason. It was the breakthrough that particle Physics was waiting for. I think it's nice that they both got the Nobel Prize because Veltman put Gerard on the right track but ‘t Hooft was the one who came up with the solution. For Veltman, however, it was crystal clear that the article would never have existed without him. So, he felt that ‘t Hooft gave him too little credit in public interviews.”

De Volkskrant

Veltman, who died in 2021, did not have a cordial relationship with De Volkskrant either. In his view, the newspaper took ‘t Hooft's side too much. He was particularly bothered by a 1997 article in which the newspaper stated that he had committed "infanticide" by failing to mention ‘t Hooft in an article about a new theory on quarks. To add insult to injury, the journalist suggested in the same piece that Veltman had moved to the United States in 1981 because he was at odds with almost the entire Faculty of Physics at Utrecht University. ‘A fallacy,’ according to Veltman.

The journalist in question was Van Calmthout. In a way, writing ‘t Hooft’s biography led him to confront his own past. “By writing this book, I automatically started to reflect on the role I played as a journalist at the time. I knew that Veltman wasn’t pleased with my article but I’ve only come to understand how upset he was right now. He even threatened to take us to court. In retrospect, I can imagine that certain parts of the article must have hit him hard. But I didn't make up those things, they were not unfair. Everything I did was according to journalistic standards, which is why I don’t regret it. But I can see how it must have been confronting to him.”

Get out of here

The depth of Veltman’s anger was evident when Van Calmthout stood on his doorstep in Bilthoven in October 1999 — on the Tuesday of the announcement of the Nobel Prize, to be more exact. In his book, he recollects what happened when Veltman realised who he was talking to: ‘He opened the front door abruptly and gestured for me to get out. 'Get out of here. The newspaper can go. The reporter is leaving.’ The memory prompts him to burst into laughter. “I was fuming for a while but I soon realised that I had a good story, so just wrote that in the paper.”

In Maar dat kan ik, Van Calmthout smoothly merges demanding topics in Physics with a vivid description of 't Hoofd's life and scientific career. He says it's not an emotional book “because Gerard is a calm, quiet man. He’s very funny but in an understated way. He’s more likely to make a little quip rather than be a jokester like Veltman was. I you want to get acquainted with his humorous side, you should visit his website. To name an example of a typical Gerard attitude, when an asteroid was named after him at the end of the last century, he responded by writing a constitution about life on his asteroid. And he didn’t stop at one or two articles, no, he wrote fourteen. One of his pet peeves is that the apostrophe in his name is consistently misused by word processors. So, he included an article in his constitution prohibiting the use of keyboards with an apostrophe on his asteroid. Hilarious, isn’t it?"

DUB is giving away three copies of Maar Dat Kan Ik

Curious about the biography? DUB has teamed up with its publisher, Prometheus, to give away three copies to our readers. To get a chance at winning, all you have to do is send an e-mail to dubprijsvraag@uu.nl with the subject Biografie Maar dat kan ik.

Martijn van Calmthout, Maar dat kan ik. Leven en denkwerk van Nobelprijswinnaar Gerard 't Hooft. Uitgeverij Prometheus, 2023. Price: 25 euros