New multidisciplinary research by professor Maaike Bleeker

How do you make a robot become more socially competent?

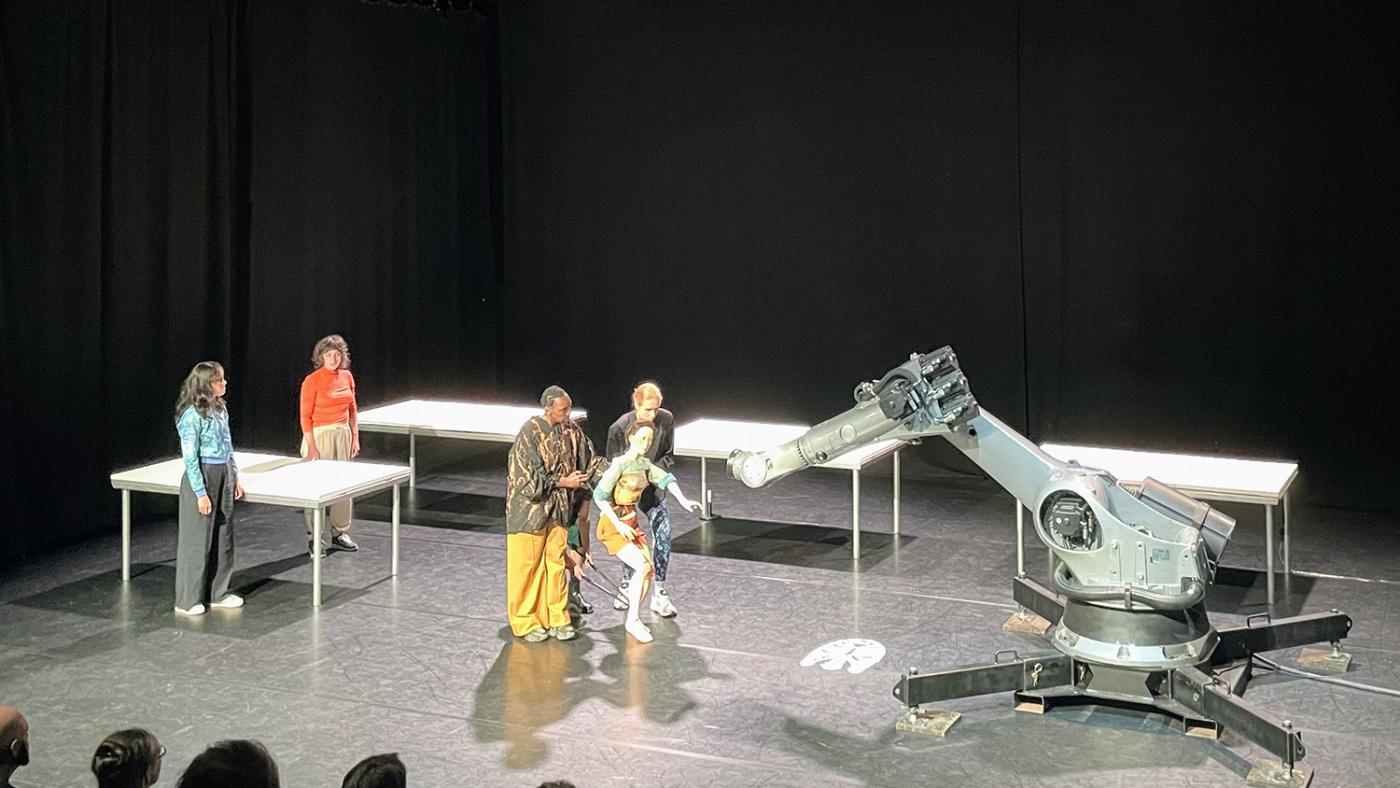

Kuka makes his debut on the stage of De Paardenkathedraal, in Utrecht, on a Monday evening in May, to the enchanting voices of the singing actors of the Ulrike Quade Company. It makes anatomical drawings on the floor with an almost hypnotic precision then dances with a Japanese bunraku doll and steals the spotlight for a solo.

Kuka, 230 kilos, consists of little more than a rotating arm. A robot arm that is, because Kuka is a machine. But that doesn't matter. Designed in 1973 by Keller und Knappich Augsburg to make cars, Kuka is given a soul as part of the robot opera Orito. That is exactly what Maaike Bleeker, a professor of Performance, Science & Technology at UU and her partners aim for: demonstrating that robots can enter into sustainable relationships with people.

Orito is based on a character from the book The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, by David Mitchell. “The story explores relationships between the human body, dolls and the soul,” says Bleeker. “At one point, the main character says that 'the soul is not a noun but a verb'. That became an important motto for our project. It says, as it were, that the soul is not in the object, but in the action. That movement is what brings a doll to life. This gives the doll an identity, a soul. We wondered whether that would also apply to robots and what it could mean for robot use in our society.”

Robotic arm Kuka on stage with the Ulrike Quade Company. Photo: Martine Jansen

Improving robot performance

The idea for the Dramaturgy for Devices project emerged about ten years ago. Bleeker was approached in Sydney by the employees of an experimental robotics project who were interested in her research into how the body is part of how people interpret the world around them. Bleeker, both a Humanities scholar and a dramaturge, then decided to delve into the matter herself. The result was a series of collaborations with people from the performing arts and robotics, which aimed to investigate what robotics can mean for the theatre and vice versa.

Those initiatives have led to the current Dramaturgy for Devices project, for which she has received a research grant of 2.1 million euros from the National Science Agenda. It is a consortium involving researchers from VU Amsterdam, TU Delft, TU Twente, people from the performing arts and the creative sector, robotics engineers, financial institutions, and social organisations. Needless to say, it is a multidisciplinary undertaking.

“The project aims to improve robots’ performance in several working environments,” explains Bleeker. “By involving people from different backgrounds, we can make robot use more attractive. Robots can already take on practical tasks, but actually integrating them into working environments remains a problem. The interaction often does not work properly. Robots get in the way, people do not feel helped enough or feel downright uncomfortable around such a device. Robots seem to lack social skills. In addition, a theatre environment can be inspiring and offers opportunities to test creative applications. Dramaturgy for Devices brings initiatives where robots are developed in collaboration with artists so that they can inspire each other.”

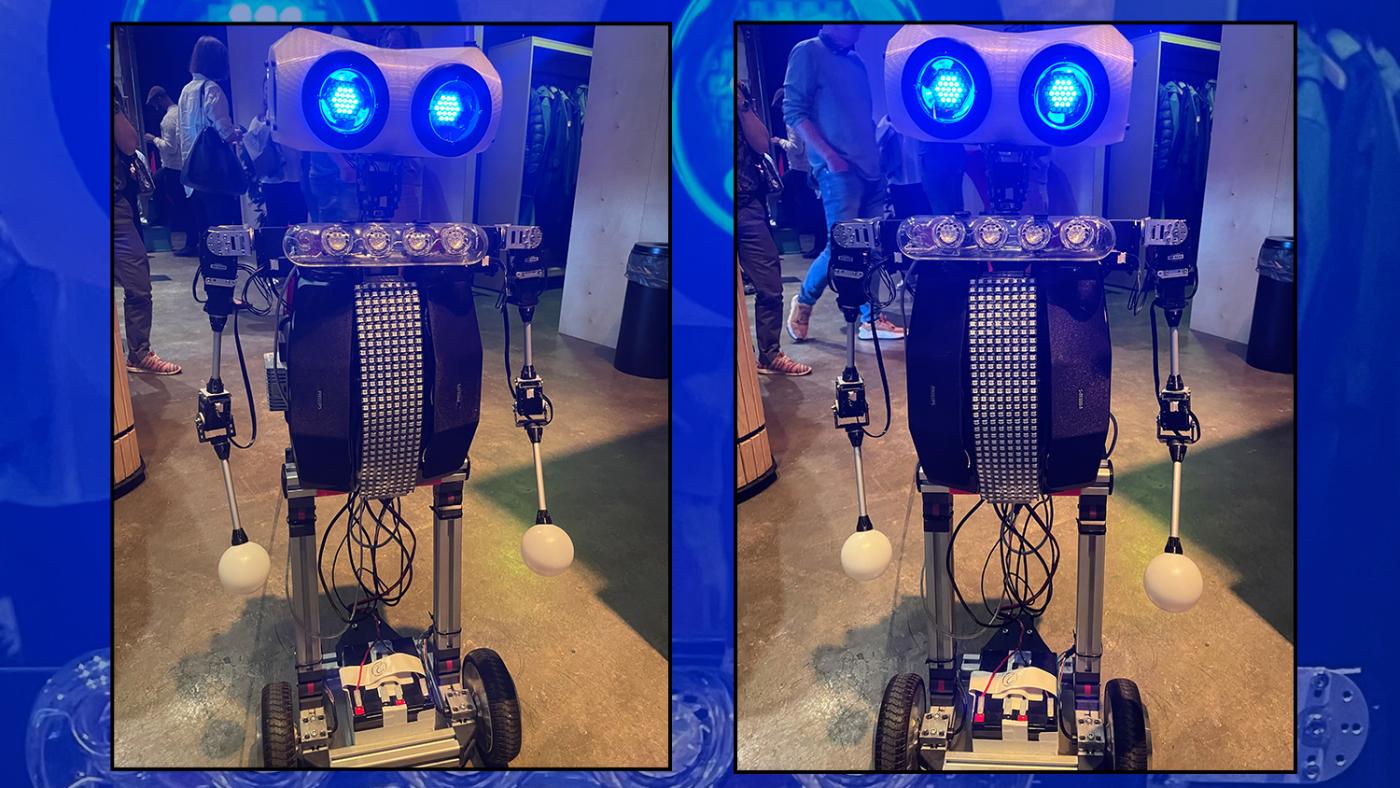

Robot Ravi by Edwin Dertien. Photo: Martine Jansen

No humanoids

Their biggest challenge will be developing the robots’ communication and behaviour. Bleeker emphasises that the robots in this project are not supposed to copy people. “We are talking about robot assistants, not humanoids like the ones we see in science fiction movies,” she says. “The robots that become part of our daily lives will not be like that. They will neither look or behave like humans nor have the same abilities we have to express, perceive, or respond to information. We want robots to behave socially without copying human behaviour, so we have to look at what robots can offer in terms of alternative expressiveness. And they can do that. Just look at Kuka.”

The search for alternative expressiveness takes different forms within Dramaturgy for Devices. For example, Bram Ellens' performance Robot from the Flea Market contributes to developing robots for the classroom. The participating researchers will develop small robots inspired by the 1967 children's book The Robot at the Flea Market by Tonke Dragt. The idea is for these robots to grow along with the mental development of the children in the classroom. “They are not supposed to act as a friend,” Bleeker explains, “but rather as an assistant to the teacher for tasks such as training certain skills or helping children who need more support. Language and narrative are important elements here. In addition to the schools and engineers, experts from the theatre are closely involved in this work package.”

The self-driving cart from Falco Robotics. Photo: Martine Jansen

Another example is the mobile cart that can be used in the catering industry for tasks such as clearing tables. “We are paying particular attention to movement,” Bleeker explains. “How do you integrate such a robot into the environment without it being a nuisance to anyone? You can imagine that choreographers are playing an important role in this process. They know better than anyone how a movement comes across in a room. For example, when do you speed up or slow down? How do you make something move through space in a way that others perceive as pleasant?”

Bleeker acknowledges that making robots more socially competent is a tricky idea which may even be seen as threatening by some. “But robotisation is not the same as artificial intelligence,” she observes. “People don't always realise that AI is already massively present in our lives. Take Facebook, for example, or the smart devices in your home. That’s all AI. This project does not aim to add AI to physical robots. The robots we are going to design must assist people, not become all-rounders, which does not alter the fact that we also need to ask ourselves ethical questions. For example, we do not want the robots to resemble people and we look critically at what we do and do not want to use them for.”