A conversation with the rector about academic freedom - part 1

'If a conversation consists of making demands, that is a complicated way of talking'

A month ago, the Executive Board received a letter from the prestigious British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. The letter stated that the institute was very concerned about the restrictions imposed by UU on the organisation of a lecture about the situation in Palestine, arguing that UU's rules clash with the freedom of expression of students and staff. The letter was motivated by the fact that the British professor Neve Gordon could not give a guest lecture about boycotts of Israeli universities at a UU building in the city centre. That's because UU does not allow events about Palestine to have more than 50 people in the audience. The letter states: “It is ironic that even activities such as Neve Gordon’s lecture on the importance of academic freedom in times of extreme violence in the Middle East are subject to restrictive measures by Utrecht University.”

Neve Gordon's guest lecture was moved to BAK. Photo: DUB

Alessandra Spadaro, Assistant Professor in International and European Law, argues that the restrictions imposed on Gordon's lecture are not only an arbitrary decision but also an inappropriate interference with academic freedom. "If we leave this choice to the Executive Board, they could decide tomorrow - perhaps under pressure from certain political or religious groups - that lectures on topics such as gender identity and reproductive rights are 'political' and may therefore be restricted," she writes in an op-ed.

Rector Henk Kummeling agrees that the communication around this case could have been better. According to him, the board does not intend to ban people or lectures at the university. "However, academic freedom is never absolute and it does not mean that anything goes. Sometimes other criteria must be considered too."

Academic freedom is never absolute and therefore does not mean that anything goes

Since last summer, the university has been applying several rules for extracurricular activities related to Gaza and Israel. “This is particularly relevant in the city centre where the layout of historical buildings, with their predominantly small lecture halls, means you have a different security situation compared to Utrecht Science Park. Consider narrow corridors to find the exit in case of emergency or fire hazards,” says the rector. “The advice from the security department is to only allow activities related to this topic in certain halls in the city centre, which can accommodate no more than 50 to 60 people. We are following that advice.” The rector adds that Gaza-related activities with more than 50 people can take place at Utrecht Science Park. However, this was never communicated to the organisers. “It is unfortunate that it did not happen.”

The poor communication about the conditions for organising a debate on the situation in Israel and Palestine sparked a discussion about academic freedom at Utrecht University. According to critics, academic freedom is under pressure even though the rector himself says he is committed to academic freedom. Do they mean the same thing when they are talking about this concept?

Kummeling: “For me, academic freedom is the space that a researcher or lecturer is given to raise new questions and tackle new problems. It is about giving scholars the freedom to explore and apply these questions to their teaching and research.” He immediately adds that academic freedom is not unlimited and not the same as freedom of expression. “Academic freedom is not a carte blanche. You are always bound by the academy and by the code of academic integrity. It must fit within the rules of academic research and the quality requirements we set for our education. A scientist must always be open to other perspectives and criticism.”

Activists demand others adopt their position. Otherwise, they are moral outcasts

That is what he misses in the university's debate with the pro-Palestine movement regarding partnerships with Israeli universities. “You must be seriously prepared to listen to each other and show a willingness to take other people's arguments into account. You don’t have to agree with them, but you must show that you understand each other’s points of view."

“We talked to the students and staff who have been protesting long before the occupations. However, they indicate that they did not experience that as a discussion. In a sense, the feeling was mutual because the discussion mainly consisted of repeating the demands, including the demand to stop working with Israeli universities. The activists demand others adopt their position. Otherwise, others are moral outcasts. If a discussion only consists of making demands, that is a complicated way of talking. It comes from a handbook for political activists that states you should not engage in conversations.”

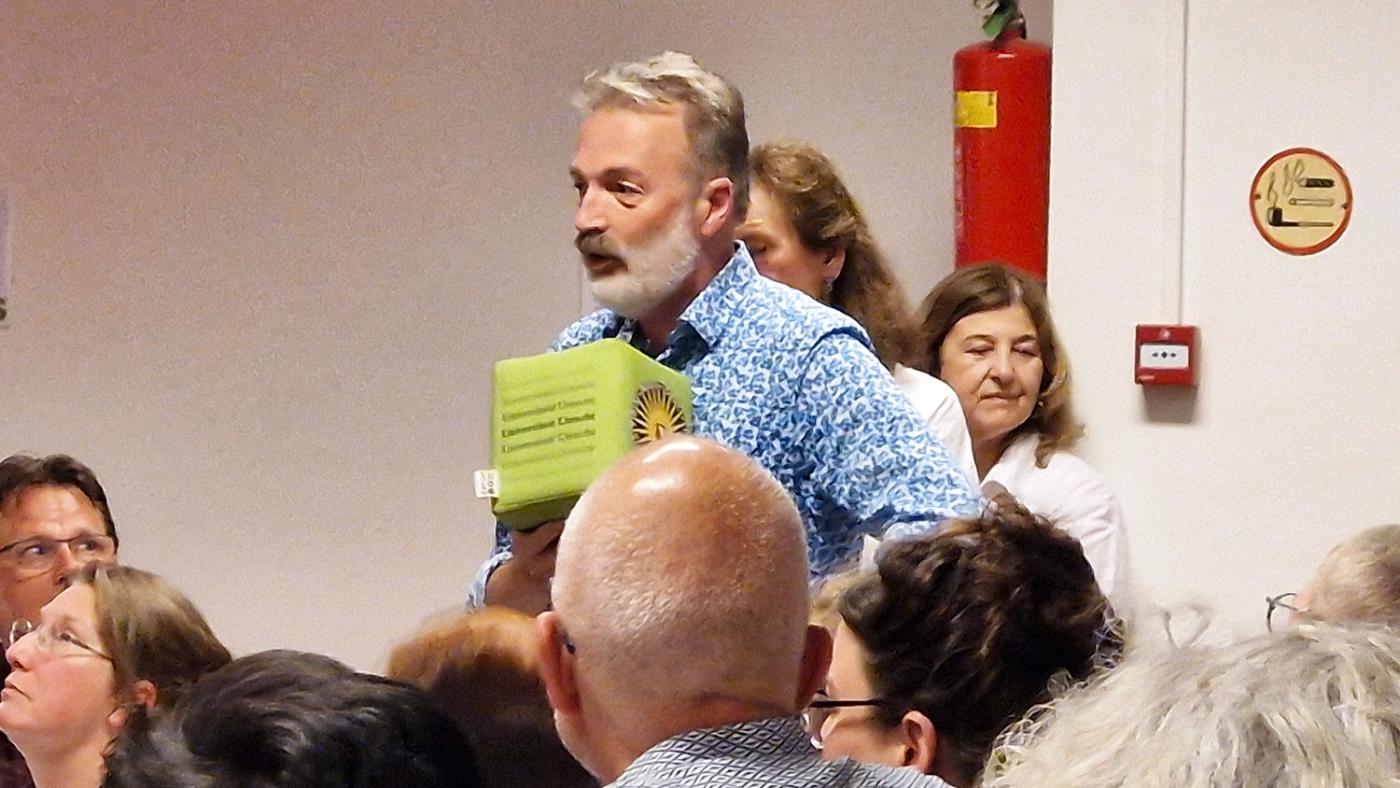

Kummeling talking to occupiers from the End Fossil: Occupy movement at the Minnaert building, March 2023. Photo: DUB

"This is not only happening in Utrecht. The same pattern can be seen at other universities in the Netherlands and abroad. The protests follow an international manual for political activists. The Executive Board has noticed this. This manual states that the strategy is to not engage in discussions with university administrators because this risks the purity of their position. The manual's authors see university and faculty councils as the executive board's accomplices, while they are precisely the body that stands up for the interests of students and employees. When I read something like that, I think: 'This means the meetings we are being asked to have do not intend to meet each other in the middle. Therefore, they do not intend to investigate we could find common ground."

Reaction UU students and staff activists

The activists see it differently. The students of Utrecht Student Encampment say they have invited the Executive Board for debates with students and staff, at a place of their choice, more than once. However, the board failed to do so each time. "It is important for us that the meeting is public because the board should be accountable to students and staff, not only in general but certainly concerning the ongoing extermination of Palestinian people and the violation of their rights, in which the university's research partners are involved."

Moreover, they say they do not work with a manual. "The only manual we follow is that of international law and scientific ethics." The UU staff for Palestine do not recognise themselves in the image painted by the rector, either. "It's a pity that, once again, the rector does not substantively address our arguments for an academic boycott, which are science-based. Instead, he comes up with unfounded and unbelievable accusations of using manuals and attacking councils. We have been in touch with members of the university council and we take their work seriously."

Pro-Palestine protesters in front of the administration building. Picture taken on May 13, 2024. Photo: DUB

Kummeling acknowledges that they received a one-off invitation before the summer break. But that the Executive Board and the UU activists could not agree on the conditions for a proper dialogue. For instance, the students and staff in question only want to engage in dialogue if at least two hundred attendees are allowed to attend, who are allowed to have their say. At the same time, the board organised a university-wide dialogue on the subject. Two students had signed up. One did not show up, the other read a statement and then walked out. Employees had immediately indicated they did not want to participate in this dialogue. The activists' method of dialogue is not working, according to Kummeling. “I attended a guest lecture by scientist Maya Wind last spring. The organisers said beforehand that the lecture would be followed by an academic dialogue in which everyone would have the opportunity to share their opinions. But that didn't happen. A panel must consist of people who dare to ask questions and critically examine the sources. However, that panel had no critical notes whatsoever, it only had applause. The only ones not taking what was said at face value were the two members of the Executive Board. That can happen, but that is not an academic conversation. It was a room full of emotion and shouting, which made me realise that inviting two hundred people for a conversation doesn't work. If you really want to try to explore each other's positions, you must make a deep investment in each other. And you can't do that with two hundred people all wanting to have their say."

The Executive Board therefore accuses the activists of not being sufficiently critical and open-minded. What about themselves? Are they sufficiently critical and open-minded? Kummeling: "We have taken a good look at our position during and following all the discussions. Are we on the right track? Do we need to investigate things further? We have evaluated and published all our collaborations with scientists from Israel. Whenever we had doubts, we submitted the collaborations to the Safety Knowledge Centre, a partnership between the Dutch government and the intelligence services providing us with information about the involvement of Israeli universities in the conflict in Gaza and the extent to which they violate human rights."

If you are truly going to make an effort to explore each other's points of view, you must make a deep investment in each other

"We have put several potential partnerships on hold, sometimes to the great sorrow of those involved. In addition, we are working on a framework for assessing our collaborations properly in the future. What kind of criteria do we need to have when it comes to the fossil fuel industry or human rights? So, we have certainly scratched our heads and strived for transparency. Strangely, Instagram posts keep repeating that we are not transparent."

The activists do not agree with the Executive Board's position. They believe that any collaboration with Israeli universities should be taboo. They do not think this would constitute an obstacle to the academic freedom of individual scientists, as the boycott concerns the institutions they believe are complicit in genocide, apartheid and colonialism through their involvement with the military industry, which enables the army's work. They also say that academic freedom is systematically under pressure at many Israeli universities due to the oppression of Palestinian students. Lastly, they mention the universities in Gaza which have been bombed.

The building of the Association of Dutch Universities, UNL, was occupied by pro-Palestine activists in June 2024.

Kummeling argues that one should not exclude all scientists from a country, no matter how wrong the regime is. “Most of the resistance against Prime Minister Netanyahu comes from universities. Many scientists oppose violence, so it is counterproductive to start excluding these people. We call that science diplomacy. Scientists are the ones who can contribute to a revolution when a regime does not operate democratically. We do set conditions for our partnerships. The scientist or institution we collaborate with must have sufficient academic freedom to work independently as a researcher or teacher. You only know that when you know someone well. If that does not go well, then we must stop the collaboration.”

He is not fully convinced by the argument that Israeli universities collaborate with the military or ministries. “We also collaborate with ministries. Due to the tense geopolitical situation, we should not rule out the possibility of also being asked to collaborate with the military or the Ministry of Defense in the future. It makes sense. The criterion is whether you have sufficient academic freedom when doing it.”

You should not exclude all scientists from a country, no matter how bad the regime is

Kummeling says that, in retrospect, he has serious doubts about the general boycott of Russian universities enforced by the Dutch government. Dutch universities had to end their collaborations abruptly. “Russian scientists have been telling us that they miss that breeding ground and the contact with our universities as that was one of the things that enabled them to work independently and contribute to a different narrative in that country. We don’t want to have anything to do with Putin or with a university in St. Petersburg whose rector supports Putin. These would have been criteria.”

An example from the past is the contact that Utrecht University maintained with the University of Western Cape in South Africa during apartheid. “That was a good thing. A breeding ground for active democracy was created, partly thanks to our exchange. After apartheid, UWC was the main supplier of the new constitution and UWC members were fully represented in Mandela’s cabinet. When I was there last year, together with the then Minister of Education and representatives of other knowledge institutions from the Netherlands, they stressed once again how important it was for them at the time to maintain a lifeline with scientists from other universities."

Henk Kummeling receiving an honorary doctorate from the University of Western Cape in September 2024. Photo: Media Office UWC

A few other things must be taken into account when evaluating international partnerships. Take China, for example. “A few years ago, the Dutch government encouraged us to collaborate with China. We had to seek partnerships with them because that was where the future lay. However, China does not have the best human rights records. Remember the Uighurs, for example. Not all universities there excel in academic freedom either. After that, we had to be cautious for two reasons. First, because of the fear that China would steal information from us in the field of knowledge security and, secondly, because people were afraid of economic competition. Six months ago, the Dutch government appointed a scientific attaché in Beijing again.

As universities, we must be able to determine our course. We should not be naive, but cooperation can work. Consider the exchange of information about vaccines during the pandemic, for example. Here too, we should only collaborate with others if the partnership benefits us and the scientists we work with have sufficient academic freedom. Otherwise, we should not do it. But, in many cases, you only experience that once you work with people.”

The conversation with the rector took place before the occupation of Drift 13 on Friday, 15 November. The second part of the conversation with the rector about academic freedom will be published soon. The second article will focus on teachers' freedoms in the classroom and the government's influence on academic freedom.