Executive Board members attend pro-Palestine event for the first time

Maya Wind: ‘Israeli universities are deeply entangled with military projects’

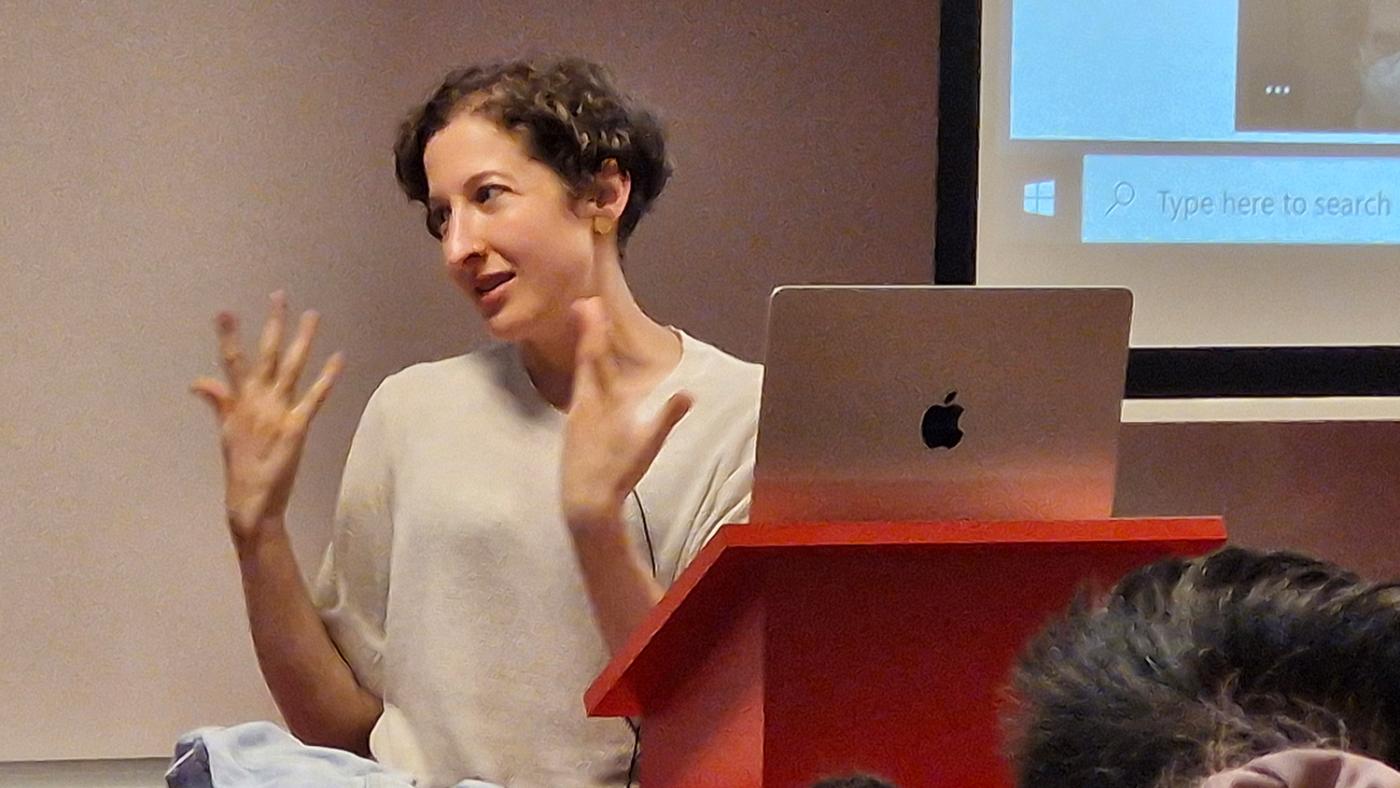

Tuesday, May 14, late afternoon. Maya Wind, the Israeli Jewish scholar who has recently published a book titled “Towers of Ivory and Steel”, about how Israel’s universities contribute to the occupation of Palestinian territories, is at Utrecht University. A researcher at the University of British Columbia, Canada, Wind is on a tour of Dutch universities which also includes stops in Nijmegen, Leiden and Amsterdam.

This is the first pro-Palestine event following two occupation attempts that culminated in demonstrators being expelled from UU buildings by the riot police. The lecture hall is bursting at the seams. Although the organisers, Dutch Scholars for Palestine, have moved it to a bigger room at Drift 13 due to high demand, that still isn’t enough to accommodate everyone who shows up. Some people sit on the floor while others have to watch it via livestream in an adjacent room. Hundreds more do the same online.

UU Rector Henk Kummeling and UU Vice-President Margot van der Starre are there as well. This is the first time that the Executive Board has accepted an invitation to an event organised by Dutch Scholars for Palestine. Up until now, the board has refused to attend “any events informing about a particular vision or position” or “proposing boycotts”. The duo justifies their change of heart by saying that Wind’s lecture is “a great opportunity to listen,” in Van der Starre’s words. “We are always critical of everything we do,” she adds.

The audience doesn’t buy it. The Q&A session with Wind (and a panel comprised of Assistant Professor Diana Vela-Almeida, Leiden lecturer Sai Englert, and UU law student Itaï van de Wal) quickly transforms into a boxing match between the attendants and the board members. Still angry about last week’s events, many students seem more interested in getting answers from the university administration than from Wind and her peers, who also take the opportunity to counterargue Kummeling and Van der Starre.

The lecture hall 15 minutes before the lecture. Photo: DUB

Embedded in the infrastructure

“While we tend to think of the military apparatus and weapons corporations as the primary drivers of colonial violence, there are other types of institutions that get far less attention but are no less central to sustaining it. The university is one such institution,” Wind begins.

She argues that universities are embedded in the infrastructure of Israel’s settler society. “And this is very different from how our own universities in the West narrate Israeli universities to us. We have been told that they are beacons of pluralism and democracy, and worthy of collaboration.” As a result, Israeli universities benefit from an exceptional status in the Middle East, as few to no such collaborations exist with Palestinian universities and other educational institutions in the region.

The granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, Wind says she was already trying to make sense of genocide long before she entered university. Her research question was inspired by the Palestinian campaign for a boycott of Israeli academic institutions, which began in 2004. Wind wondered if Israel’s universities were indeed complicit in the occupation and, if so, to what extent. She spent several years going through the Israeli state and military archives (to which Palestinians have no access) as well as media reports and academic theses. A trained ethnographer, she also visited the campuses of eight major Israeli universities to witness classes, events and protests, and talk to both Palestinian and Jewish Israeli faculty.

Her conclusion: from the onset, universities have been central to Zionism and its aim to replace Palestinians with Jews, establishing a majority that would pave the way for the foundation of a Jewish state. Before this state was even founded, the Zionist movement established three universities in key areas to increase its technological and scientific capacities.

Anthropologist Maya Wind. Photo: DUB

Once the Jewish state was created on May 15 1948, Wind continues, the government renamed the settlement project Judaisation. “This is not a term coined by academics,” she stresses. “It is the official terminology!” She explains that the project involved shrinking lands in Palestinian possession, interrupting Palestinian territory continuity, expanding Jewish settlements, and facilitating the permanent transfer of lands from Palestinian hands to Jewish Israeli possession. “Then, in the 1960s, Israel opened even more universities to anchor this territorial and demographic programme in regions of strategic concern.” The University of Haifa, for example, was founded in the only region that still had a Palestinian majority after 1948. “They were thought of as ways to normalise the settlement and bring more Jewish Israelis to those areas.”

According to her, all Israeli universities have offered facilities, faculty and expertise for Israeli military training. For instance, some universities developed specialised degree programmes for soldiers in conjunction with the Ministry of Defence. They also helped Israel develop its own military technology and weapons. “One cannot understand certain disciplines in Israeli Academia, such as Archaeology, Legal Studies, and Middle East Studies, apart from these ties to the state.”

In addition, Wind argues that Israeli universities have actively suppressed critical academics. In 1978, Israel declassified important materials about the establishment of the Jewish state. Although they were still inaccessible to Palestinian scholars, they enabled Jewish academics to find evidence of the mass expulsion of Palestinians and massacres that occurred in the 1948 war, confirming previous works by Palestinian scholars. Wind remarks that these Israeli researchers have faced “immense backlash”, so much so that all but one of them now live abroad. “Many of the archives have since been reclassified and Israeli universities never opposed this censorship of academic research.”

Wind’s lecture not only denounces the complicity of Israeli universities with state violence against Palestinians, but it also draws attention to attacks against Palestinian academia. “In the past seven months, Palestinian universities have been all but destroyed. Over 9,000 people were left without access to education. Not one Israeli university has called on Palestinian universities to be spared.” In her view, we are witnessing not only a genocide but also a “scholasticide” in which centuries of knowledge production are being destroyed. “But this war against Palestinian scholarship and education has not started seven months ago. Palestinian scholarship has always been considered a threat to Israeli rule.”

Wind finishes her lecture by complimenting the protests requesting Utrecht University to end its partnerships with Israeli universities. “We can hold our universities accountable to the values they say they hold. There is no academic freedom until it applies to all of us.” She is cheered with a long applause.

Executive Board members steal the scene

After Wind’s address, each of the panellists gets to make a speech. Englert, from Leiden, underscores that Dutch universities are falsely portrayed as apolitical spaces as if they didn’t participate in politics and had no connections with the state. “Discussing Israeli universities gives us tools to think about our own universities.” Vela-Almeida, from the Faculty of Geosciences, notes that it is “ironic” that UU justified the use of police force against protesters on the grounds of safety, but dropping students “in a remote place in the middle of the night” compromises their safety. Van de Wal stresses that UU has “no human rights policy” governing its partnerships and calls on students to strike the following day to gather at Janskerhof instead. This call will result in the occupation of Janskerkhof 15a.

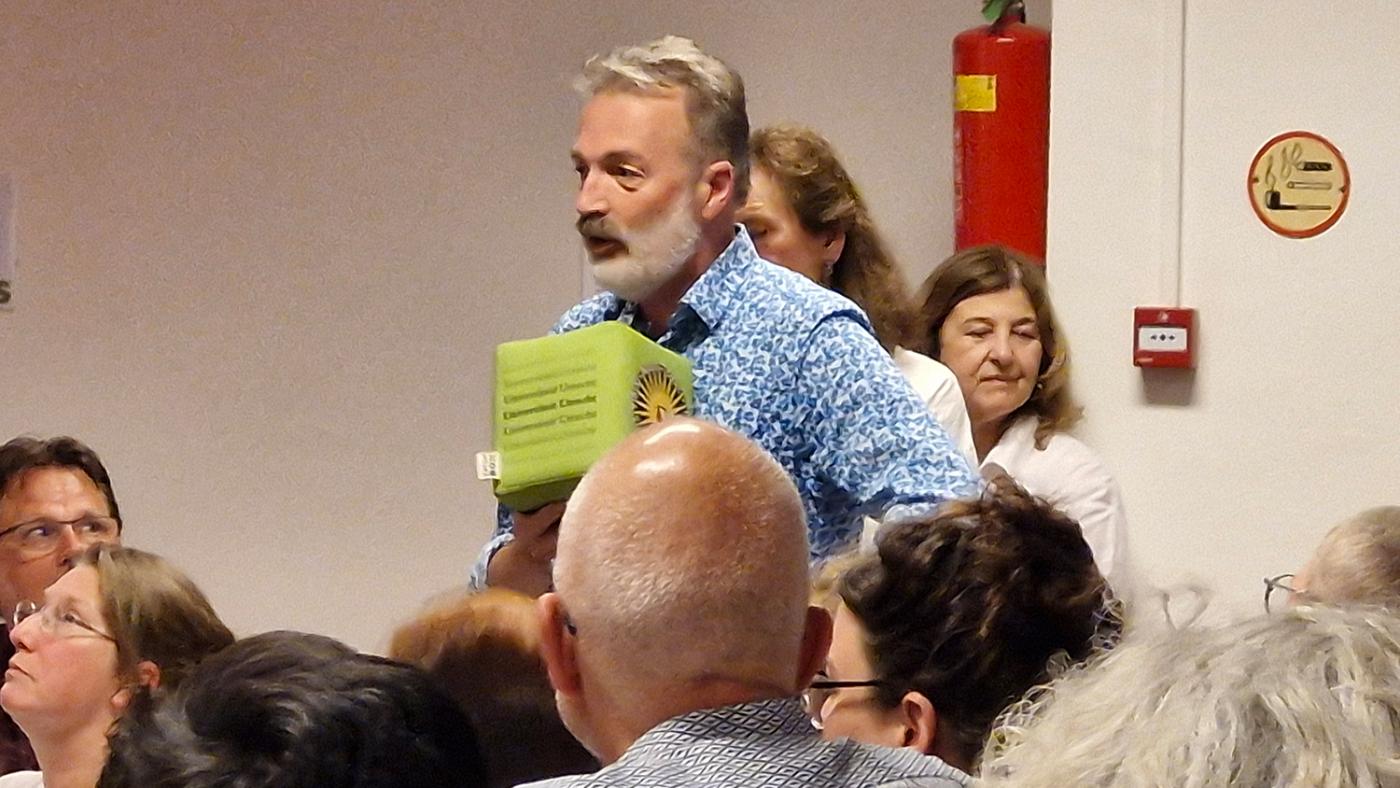

Once the Q&A session starts, a student asks why universities are holding on to their ties to Israeli universities “even though this gives them a bad reputation”. The event’s host, Layal Ftouni, says: “We have two members of the Executive Board here, so why don’t we ask them?” Rector Henk Kummeling replies: “We don’t even dare argue with the facts Wind has presented. For me, one of the most important questions here is: do Israeli universities have the power to transform themselves? I don’t think all our colleagues in Israel support what is going on.”

The event’s host, Layal Ftouni. Photo: DUB

The rector stresses that UU wants to be transparent, which is why it will publish an updated list of collaborations with Israel this weekend. “We are also going to look once again at whether or not these partnerships meet our standards in terms of human rights.” The rector then adds that the Executive Board doubts that severing all ties with Israel would be the best solution. “We did that with Russia, under the request of the EU and the Dutch government, and we now see the terrible results of that.”

He is interrupted by a student, who shouts: “You’re not answering the question!” to which Kummeling replies: “I am answering the questions I wanted.” The audience laughs and shakes their heads in disapproval. Nevertheless, the board members are applauded for their presence.

Executive Board member Henk Kummeling. Photo: DUB

The panellists then jump in to counter Kummeling’s arguments. Wind says: “I hear repeatedly on campuses everywhere this concern for the wellbeing of Israeli academics, but no such empathy is extended to Palestinian academics. This is something we should be attentive to.”

She then quotes the head of Israel’s National Security Institute, who, according to her, said in the Israeli media that “international collaborations and ties are the oxygen of Israeli universities and Israeli universities are the oxygen of the military”. Finally, she underscores that there is a historical precedent of academic boycotts working (against South Africa during Apartheid, for example). Teary-eyed, a UU teacher from South Africa in the audience says: “I wouldn’t be here if students hadn’t mobilised.”

The panellists and the audience take turns arguing against the Executive Board members. Outnumbered, they take the punches mostly in silence. Englert says UU only regrets breaking up with Russian universities because it “set a complicated precedent.” One student sees a “lack of moral leadership” at UU, while another one wonders why the decision lies entirely in the hands of three people. “Don’t follow the lead of the government. Take the lead!” says another. Kummeling reiterates that “this is a learning opportunity, also for us on the board. Allow us to at least digest the information we gathered this evening.” Van de Wal retorts: “This has been going on for 75 years and you haven’t learned yet? There are many scholars in this university studying just that. Do your research!”

The atmosphere gets tense and the event’s host, Layal Ftouni, decides to end the session, but not before addressing the Executive Board herself. She announces an expanded list of demands. The protesters would like representatives of students and staff to have a seat at the table in the process of re-examining the partnerships. They would also like the conclusions of this reassessment to be made public before the summer break. Additionally, the group wants the university to apologise for deploying the police last week and provide psychological support to students who have been physically harmed. The two board members didn’t react to the new demands.