UU teachers speak up for Palestine

'We’re fighting against Utrecht University's bystander position'

Students weren't the only ones disrupting UU's anniversary celebrations (also known as Dies Natalis) in March. Scientists did it too. The ceremony, which took place at Dom Church, had The Future of Democracy as its theme. The scientists protested against the university administration's decision to remain "neutral" regarding Israel's attacks against Gaza, which are taking genocidal contours to many. The protest was not initiated in a heartbeat. Instead, the three teachers say it was a reaction to being ignored and deferred by the Executive Board for months. Numerous open letters and petitions called on the university to sever its ties with Israeli universities. Talking to DUB, they reflected on the events leading up to the demonstration at Dom Church and the circumstances that made them conclude it was necessary. The Executive Board's response can be read at the end of this article.

"It's now or never"

“We enter Dom Church and realise the significance of the event. We had talked about possible repercussions, but actually being there is something else,” says Eva Hayward, Assistant Professor in the Department of Media & Culture Studies. Sitting in the audience beside her colleagues Layal Ftouni and Kathrine van den Bogert, she feels the gravity of the situation. “It’s just going to be the three of us up there.”

At that point, students had already been thrown out after disrupting the Dies Natalis event to call for solidarity with Palestine. “The proceedings just went back to normal. During his speech, Rector Henk Kummeling said: ‘This is an example of democracy in action.’ Rather than listening to the students, he co-opted their protest to nullify their action,” states Hayward.

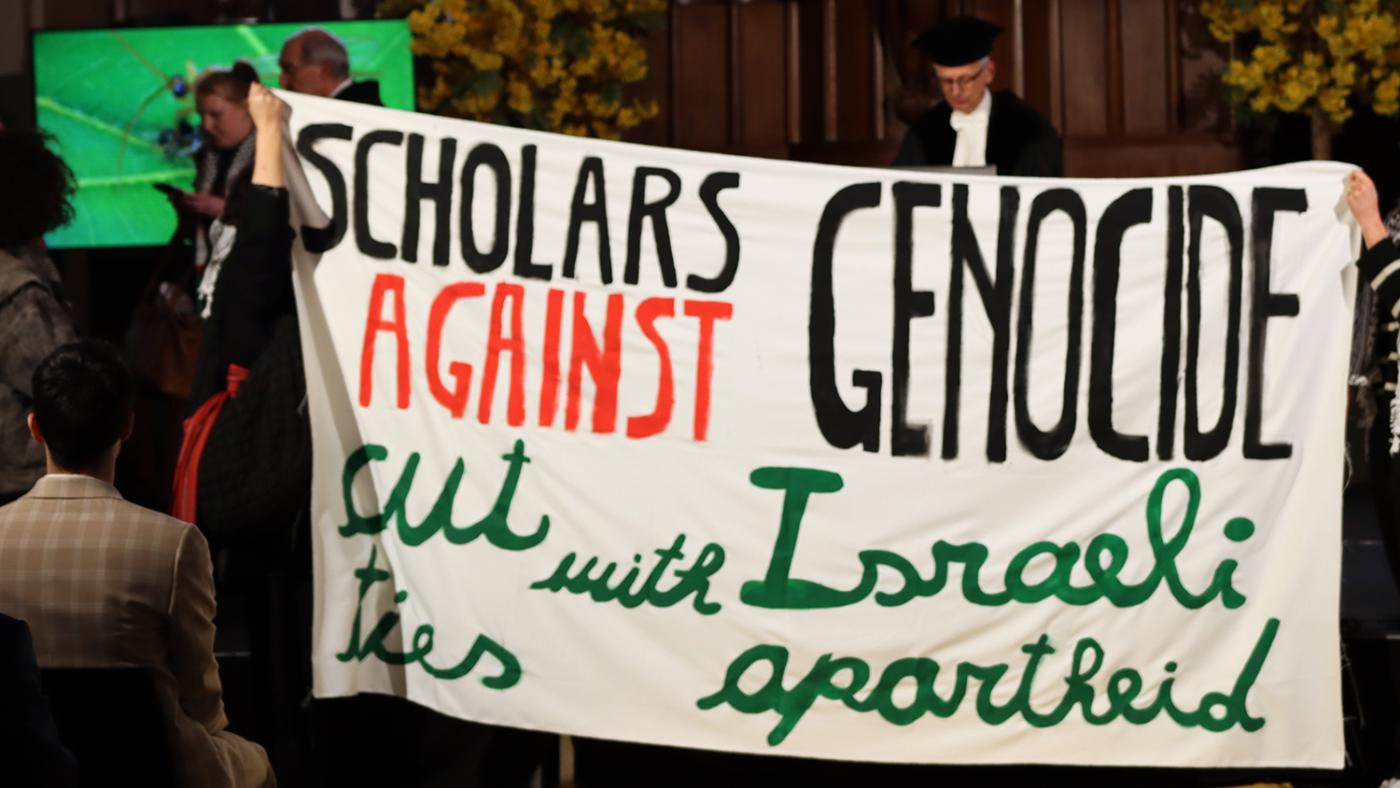

Despite their hesitations, they look at each other and say: “It’s now or never”. Holding a banner saying “Scholars Against Genocide: Cut Ties with Israeli Apartheid,” they stand up and interrupt the keynote speaker, Mark Bovens, who is talking about zombie democracies. Although Hayward, Ftouni and Van den Bogert are the ones visibly carrying out the protest, they are not alone. A fourth protestor, a graduate student, also participates. They are equally supported by several people in the audience, including other faculty, some of whom give them a standing ovation or wear keffiyehs. Many others, though not present in the audience, had contributed to the preparations for the protest. Some, however, do not feel safe or comfortable to protest with the three women onstage.

“It is important to mention that we were the ones onstage because we are less afraid of repercussions. We are on tenure and not in immediate danger of lasting consequences, like losing our jobs,” explains Van den Bogert, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance.

The collective

The women are part of a collective of academics and scholars committed to the Palestinian cause. It is not an institutionalised group, but rather a dynamic and diverse collective that continues to grow. “If you had asked to speak with us a couple of months ago, you probably would have talked to other people,” notes Hayward.

The disruption of the university’s anniversary was not a standalone action. Instead, it was the final straw for this collective of UU students, employees and faculty who felt dismissed and not taken seriously when calling for a dialogue with the Executive Board about how the university should respond to the situation in Gaza. They are calling on the university to establish an ethical framework for educational and research partnerships, which would include cutting ties with Israeli universities, which are deemed complicit in genocide and the occupation of Palestine.

Opposing the university's "neutrality"

Protests in favour of the Palestinian cause long precede Hamas’ attacks on October 7 and Israel’s extreme reaction, which has been ruled by the International Court of Justice as a plausible genocide on January 26. The trio explains that protests have been carried out ever since Israel occupied Palestinian territories 76 years ago. However, the events from October 2023 have intensified the demonstrations and calls for solidarity. Something started brewing within UU’s academic community, with employees and students from all faculties organising protests in solidarity with Palestine.

The first time students and staff manifested their disapproval of the university’s lack of response to the crisis was on October 23. An open letter with 1,275 signatories urged UU to break ties with Israeli universities and called for a strong condemnation of genocidal actions against Palestinians. UU released a statement the day after, condemning the violence but refraining from supporting either side. The Executive Board argued that it is not the university’s role to take a stand because it is a university, not a political institute. They left the dialogue up to the academic community, without getting involved themselves.

This “neutral” policy dictated their modus operandi in the months that followed: the board maintained the same argument despite multiple calls to reconsider. To Layal Ftouni, Assistant Professor of Gender Studies and Critical Theory, this is typical at Dutch universities. Before coming to the Netherlands, she was a student and teacher in the UK, where she says that universities are considered places for political nurture. Here, “diversity and internationalisation are welcome and encouraged as long as they can advance the image of the university as an open and inclusive space. Once you’ve been ‘included’, you realise that you’ve entered a very apolitical space where being politically vocal is seen as troublemaking.”

However, Ftouni continues, “We can’t separate politics from our scholarships. We are Humanities and Governance scholars. This idea that scholars should perform a neutral position, flattening power relations, and equating the oppressed and the oppressor, is a fallacy. What is education if it is not committed to social and political justice?”

Demanding an answer

The second open letter to the Executive Board, sent on November 21, was signed by 1,024 students and staff members. Its main purpose was to debunk the university’s neutral position, arguing that it normalises genocide. It ended with the same demands: calling for an immediate ceasefire and breaking ties with Israeli universities. The Executive Board didn’t respond to it. An e-mail on behalf of all signatories followed, requesting an answer by December 18, but the deadline passed without a reply.

A third letter was sent on December 19 and, although it did get an answer, the board reiterated its initial statement, saying that taking a stand would only feed polarisation. By exercising restraint, the board believes it is providing students and employees with an opportunity to investigate, debate and express their views independently. In a written response, the collective expressed its disappointment in the board's "indifference towards genocide and its inability to understand that the university is a bystander by taking a neutral position," explains Ftoui. “We wanted to expose the limits of a ‘neutral’ discourse and how neutrality means a refusal to recognise one of the worst humanitarian crises in recent history."

In the third letter, the collective also asked to meet with the Executive Board. The board replied to their request three weeks later, after getting a reminder on January 9. They invited the letter’s authors to meet them alongside other colleagues on January 30. Meanwhile, the International Court of Justice ruled Israel’s actions as a plausible genocide. “We felt we had even more leverage for this conversation,” says Ftouni.

The meeting went well, with participants feeling that the Executive Board had listened to them. So much so that they expected the university’s administration to reassess its statement in light of the ICJ ruling. “We were really hoping this would be the starting point of a series of conversations in which we would work together as a university,” Van den Bogert admits.

She continues: “They said they would come back to us after discussing the issue with other Dutch universities, but then we didn’t hear from them for weeks. By merely saying ‘we don’t know yet, we are still talking to other universities,’ they are buying time in a way.”

While they waited for a change of heart, the collective organised more events for the Palestinian cause, such as a public meeting with academic experts on February 12 and a walk-out/alternative teach-in at the UU library one month later. The Executive Board was invited to both events but declined to attend. However, its president, Anton Pijpers, was present when students occupied the dining area of the city centre library, on February 22. He engaged with the occupiers and talked to students about democracy at the university.

Clashing with colleagues

According to the three protesters, the Executive Board is not the only one adopting a neutral position. Van den Bogert, Ftouni and Hayward were confronted with similar attitudes in their departments, where they say their actions have been met with either silence or disapproval.

“We reached out to the deans about the teach-in and some of them said they wouldn’t come to our events because that would clash with UU’s neutrality. One dean explicitly used that reasoning to not even talk to us. This costs us a lot of energy. We can continue organising public events and we are allowed to do so, but if that doesn’t change anything in the end, I don’t even know what to say…” sighs Van den Bogert.

Ftouni adds: “Their refusal to have an open dialogue with us shows how neutrality is a form of active disengagement. When they say ‘we are neutral’, what they mean is that they don’t want to engage anymore. That’s it, we’re neutral. It’s the end of the dialogue. There is no other argument. It is extremely frustrating.”

Back in October, Ftouni circulated a letter written by Dutch Scholars for Palestine in her department, Media and Culture Studies, asking colleagues to consider signing it. She attached a few articles to it to contextualise what was going on in Gaza. One of her colleagues called the letter “anti-semitic,” which resulted in a heated exchange with Ftouni. Hayward then tried to reply to “spurious” statements about Ftouni’s emails, only to discover that the email list had been disabled and the discussion moved to Microsoft Teams.

Ftouni: “The decision to disable the mailing list without prior notification is a form of censorship, especially when a letter is described as ‘anti-semitic’ by a colleague. It is dangerous how this reckless accusation of racism is thrown around so lightly against those who oppose genocide. How do you think this feels for me, being the only Arab professor in the department at the time?”

According to Hayward, Van den Bogert and Ftouni, UU’s neutral policy is striking, considering protestors back up their demands with scholarly arguments and universities should promote scholarly debate regardless of the sensitivity of the subject. “The petition letters we sent were backed up with a plethora of expert sources, from UN rapporteurs to Holocaust and genocide studies scholars, but they refused to engage with any of it. All these people, who have a wealth of knowledge, experience, and expertise, were completely dismissed. The signatories, many of whom were members of staff, were dismissed,” says Ftouni.

The last straw

A couple of days after the ICJ ruling, Dutch Scholars for Palestine (DSP) published an open letter to all higher education institutions in the Netherlands, asking them to re-evaluate their initial statements. According to DSP, the Palestinian cause is no longer a question of academic debate, but rather a matter of international justice and peace, and respecting a ruling by the highest international legal institution. In addition, DSP denounced the complicity of Israeli universities in upholding Israel’s illegal siege of Gaza and the illegal occupation of the Palestinian Territories, which is why they are in favour of severing ties with those universities and developing ties with Palestinian institutions instead. “Some universities answered our letter publicly, but UU did not reply at all,” sighs Van den Bogert.

After trying for months and getting nothing but radio silence, the protesters concluded that a more disruptive demonstration was necessary. Van den Bogert: “We concluded that, no matter what we do, they don’t ever respond to any of our invitations for a follow-up or come to any of our events.”

Taking the stage

The moment has come to take the stage. Van den Bogert does the speech, Ftouni films it, and Hayward holds the banner alongside a graduate student. This is where things get intense: Pijpers gets onstage while Van den Bogert is speaking and tries to get her off. “He grabbed me by the waist and tried to push me really hard off the stage. I had to stand my ground to continue the speech,” she recollects.

“I just focused on finishing the speech. I was completely shaking afterwards. It was only then that I realised what had happened. It is very threatening when the highest boss of the university is trying to push you off the stage, while you are trying to talk to them in an event about democracy.”

Ultimately all three, plus the graduate student, are ushered off the stage and out of Dom Church. The event picks up where it left off.

Aftermath

After the protest, Van den Bogert, Hayward and Ftouni are apprehensive about returning to their workplaces. They have no idea what to expect. Hayward: “I haven’t been to the office afterwards, but none of my colleagues have reached out to talk about the protest. I got nothing but silence, even from like-minded faculty, people I respect and who I thought would speak up.” She says they haven’t been reprimanded for what they’ve done, but there appears to be a limit to commitment and solidarity. “The institution seems to hope that our efforts will just sink back into the apolitical landscape. It’s just crickets…”

Van den Bogert feels the same: “Apart from one colleague, no one talked to me about it, even though I know many people who were there. They acted as if nothing had happened and just talked about normal daily things. I avoided going there, but they have my e-mail and phone number.”

Although the protest and other actions have not led to a dialogue with the Executive Board, the collective is still adamant about making this happen. After all, they believe the university has the power to change public opinion and set things in motion. “We cannot single the university out as a neutral institution that has nothing to say in public debates or issues," says Ftouni.

Van den Bogert adds: “Of course, the university is unable to stop the bombs, but taking a stand makes a huge difference. It could help push the whole civil society to stop supporting the Israeli government. Our government continues to send F-35 materials to Israel, which are being used to bomb Gaza. The university could challenge the Dutch government about this.”

Speaking up for Palestine is not the collective’s only goal. They also want to raise awareness of how universities should deal with genocide and violence all over the world. Hayward: “This is a step towards that future, to no longer have universities complicit in genocide and the brutalisation of peoples around the world.”

The Executive Board reacts

The Executive Board partakes in the concerns about the current situation in Israel and Gaza. We are watching with horror the human suffering caused by this new cycle of violence between Israel and Hamas, and we hope that the conflict will end as soon as possible. This question has been demanding the Executive Board’s attention daily and in many ways.

Several parties have been asking us to adopt a (political) position in favour or against one of the warring sides, and we have been criticised for not doing so. In our view, such a position would not suit us as a university. This point of view shouldn’t be confused with indifference, for we are obviously not neutral towards human rights violations. We share feelings of sadness, bewilderment and powerlessness about the violence and the human lives lost. We sympathise with everyone affected by this conflict, regardless of their side. We attach great importance to rulings such as the one by the International Court of Justice and resolutions such as the one by the UN Security Council calling on Israel to combat famine in Gaza, as well as pleads for Hamas to release all hostages and calls for an immediate cease-fire.

Throughout the past few months, the Executive Board has received many letters, petitions and verbal reactions regarding the conflict. Although we have spent a lot of energy responding to questions, remarks and concerns, we haven’t always been able to reply to everyone or reply to them timely. This doesn’t mean that we haven’t read the letters or that we’re not listening. We have been in contact with the colleagues mentioned in this article several times. In addition to e-mail exchanges, the Executive Board met two of the three employees in a meeting that lasted about an hour. We regret to read that they still don’t feel heard.

Indeed, the Executive Board has been invited to join several activities surrounding this topic. We did not attend events informing about a particular vision or position, or events that tried to enforce a given position. Neither have we accepted invitations to events proposing boycotts. Moreover, the board members didn’t always have space in their schedules to join the events, which were often announced at short notice. We do not think that cutting or halting all contact with a country’s institutions is the answer. Instead, we stress the importance of a dialogue with students and employees from regions in conflict as they are the ones who can best contribute to change. We have done so in the past, after Russia invaded Ukraine, under the request of the Dutch government and the European Union.

The involvement of students and colleagues is also an important contribution to societal change. We value how our scientific community contributes to a better world daily, and how they clarify this conflict in the media. Protesting is another way people can be involved. The article above alludes several times to protesting having consequences. Protesting and demonstrating are part of our democracy, provided that said protest respects others and everyone adheres to the house rules.

Kathrine van den Bogert describes her experience of the Dies Natalis ceremony. When she interrupted the keynote speaker, there was an attempt to get her offstage in a calm manner. It is a pity to read that this was experienced differently by the colleague in question.

As a university, we believe that ensuring that UU is and remains a safe space for all students and employees is of utmost importance, regardless of their origin, background or political views. We are concerned that this no longer applies to everyone since October 7, which is why it is perhaps more important than ever for the university to be a space for academic debate, however with explicit respect for other people’s opinions.