Survey of students and employees at six universities

Internationals feeling less welcome due to political climate

The position of internationals at Dutch universities is one of the hot topics in the upcoming elections for the Dutch Parliament. Right-wing parties, such as NSC, recently formed by MP Pieter Omtzigt, are worried about the number of international students coming to the Netherlands. A motion from the political party NSC asking to reduce the number of English-taught programmes offered by universities was supported by many other parties.

In Denmark, the number of English-taught programmes was drastically lowered in 2021 but the government was forced to make a U-turn last month after employers complained about the lack of highly-skilled workers in the labour market.

How does this debate make international students and staff feel in the Netherlands? Are they afraid of no longer being welcome in the country? To answer these questions, international students and staff from the universities of Groningen, Utrecht, Nijmegen, Delft, Wageningen and Twente were asked to answer a questionnaire on the topic. The survey was initiated by UKrant, DUB’s equivalent at Groningen University. In total, 1,330 respondents answered the survey, of whom 294 were from Utrecht University.

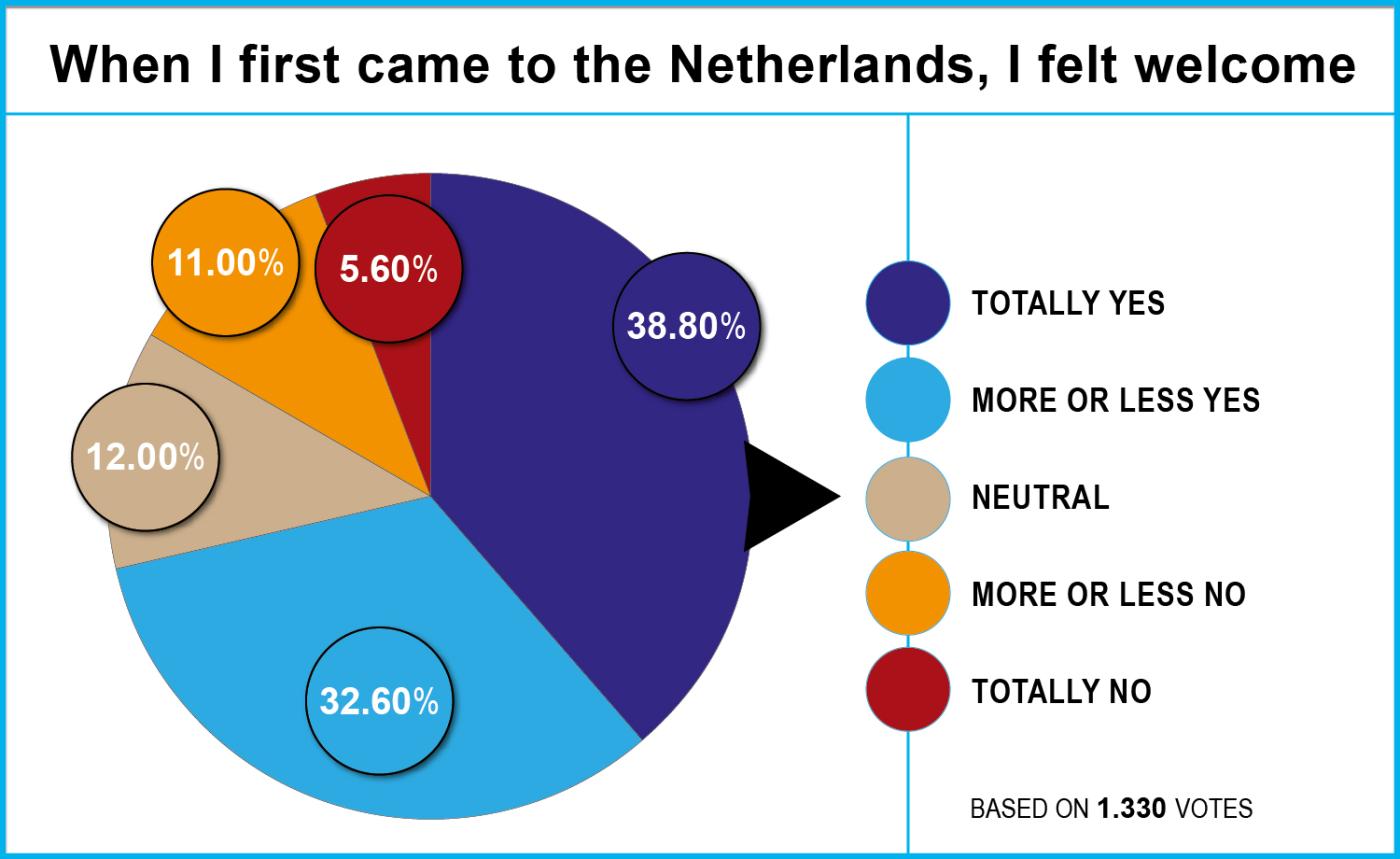

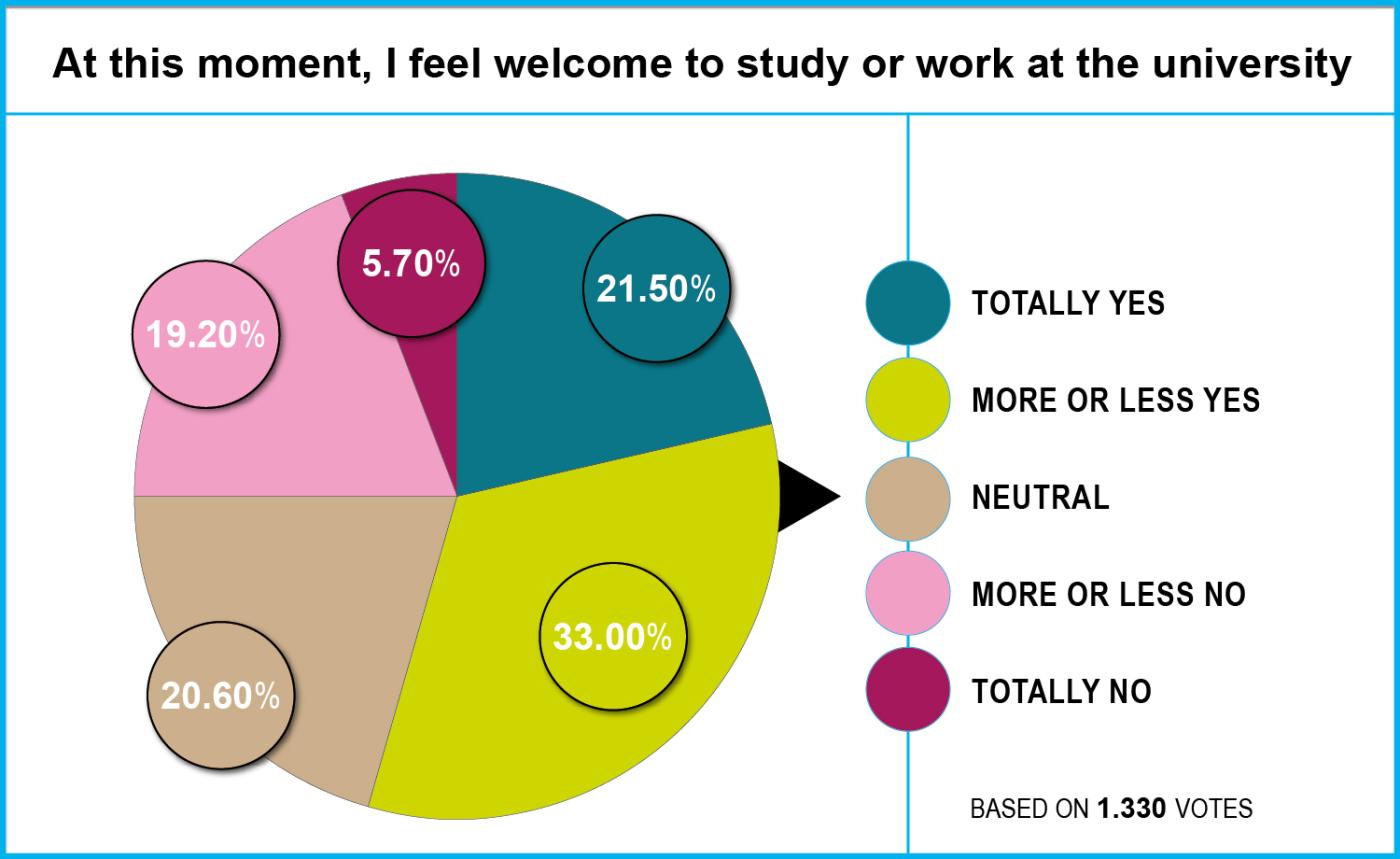

The results show that international students and staff members of all participating universities do feel less welcome indeed, compared to when they first arrived. Respondents were asked to indicate how welcome they felt on a five-point scale both at the moment of arrival and at the moment they took the survey. On average, the score dropped by half a point, which means they went from feeling somewhat welcome to feeling neutral. The increasing negativity about international students and staff among Dutch politicians was mentioned by approximately 50 percent of respondents as a reason for the drop. Nearly 30 percent of UU respondents also noticed that Dutch media is increasingly negative about internationals as well.

An invitation to discriminate

The students and staff who answered the questionnaire used terms like “sad”, “worried”, “uncomfortable”, and “concerned” to describe how they felt. “I feel uneasy that these sentiments are being aired so widely and publicly. It sometimes feels like an open invitation to discriminate against outsiders, an easy target to blame,” writes a Master’s student from the Faculty of Humanities.

A German researcher, also from the Faculty of Humanities, adds: “I am shocked how in the past 5 years since I arrived the discourse has changed from a rather ideological endorsement of internationalisation, as if it was a goal in itself, to a similarly ideological rejection of internationalisation, as if it was the source of all social problems, from the housing crisis to work pressure at universities.”

Some of the respondents understand that Dutch people are critical of the number of international students because of the housing crisis and the fear of losing their own language. But most respondents consider this view rather short-sighted and they feel as though international students and staff are being used as scapegoats in the political debate. An international staff member from Romania says: “The debate on internationalisation is a red herring in Dutch politics. They are treating it as the root cause of the housing problem and not as a symptom of a structural problem the Netherlands has been having for years now. I feel that pushing international students to the forefront of these public debates amounts to scapegoating them, viewing them as a pest to be rid of. This is very worrying and is avoiding the real problem: the Dutch housing market is broken.”

A Master’s student from the Faculty of Geosciences argues that this way of thinking is bad for the country: “I think it is very dangerous for Dutch society to keep closing, considering its long history of trading and international relations with other countries. The Dutch economy very much benefits from an international workforce contributing with taxation money and expertise. Making Dutch society uniform can possibly dampen developmental processes.”

Not going anywhere

Within the university’s confines, internationals feel welcome when it comes to academic matters, although things are much harder in terms of making friends and socialising. Language is one of the main reasons mentioned for this. A Master’s student writes: “In class, I mostly do feel welcome and Dutch people are equally as nice as anyone else in my courses. But they do clique off into groups quickly. They separate away from internationals mainly because of the language, I think. Outside of university, I work in the hospitality sector, where I feel a growing anti-international sentiment mainly surrounding the lack of Dutch skills.”

But this doesn’t mean that the majority of respondents are planning on leaving the Netherlands. On the contrary: 54 percent of them hardly think about leaving the country at all. Although most of them have no intention of staying here after they finish their PhD, others are looking to stay here because they have a relationship with a Dutch person or because they like the country despite the political climate. A Bachelor’s student from France notes: “I doubt any other non-English speaking country in the world would be as good to live in. Even with this debate going on, it doesn't change the fact that every Dutch person can speak English, which is extremely important and handy when living here, and are welcoming to internationals overall.”

A bit bitter

But there are internationals who have changed their minds about staying here because of the attitude towards internationals, such as a Master’s student from Thailand, studying at the Faculty of Humanities: “I initially came here to stay, but since discrimination and hate against internationals are rising, and the Netherlands is becoming more and more conservative, I am second-guessing that decision. If causing discomfort for international students in order to get them to leave once they graduate is the government's tactic at all, then they are on their path to success.” A staff member from Turkey, also working at the Faculty of Humanities, thinks he has been tricked. “When I came here, I had options to work in other countries and at universities where English is the primary language of instruction. I was told back then, to be lured to UU, that internationalisation is a major aim of the university and English will be the main language of instruction. I feel like what's happening now is not fair game to internationals.”

Some respondents can’t help but be a little bitter when they comment on the change in attitude towards international students and staff. A Master’s student from Ireland argues: “I think a lot of Dutch people have no understanding of what it’s like to move to another country by yourself, with no support network, and start life from nothing. They don't understand how dehumanising it is to find yourself in the middle of a conversation understanding absolutely nothing about what is being said or to feel like you're a burden on everyone because they ‘have’ to speak English for you.”

More support from the university

A British scientist from the Faculty of Geosciences says he moved to the Netherlands in 1997 and was initially proud of his decision. “The Netherlands had a culture that was almost unique in Europe and possibly in the world. One of openness and tolerance. A culture that anything is possible, with boundaries only set for actions considered antisocial. Since I have lived here over the last 25 years this image has slowly eroded.”

In his view, UU should be doing more to support international students and staff. “Policy statements from leading UU members are lacking in this debate. The current atmosphere seems passive, with a ‘wait and see’ message percolating through the staff ahead of the outcome of the election. It would be great to see more leadership from deans and/or the Board to our minds at rest and support the diverse and vibrant community of internationals that we have within our ranks. Political debates such as this one can be polarising and a potential minefield for UU policymakers, but I’m sure a carefully crafted and nuanced response to this debate is possible. This is an aspect of Dutch culture that remains and I am very proud of.”

About the survey

A total of 1,330 people answered the survey, of whom 294 either study or work at Utrecht University. Of these 294, 144 are Master's students, 28 are PhD or postdoc candidates, 8 work as support staff, and 40 are scholars. 30 percent of UU respondents are male, 61 percent female and 6 percent are non-binary. 3 percent of respondents preferred not to disclose their gender.

Participants were asked if they felt welcome in the Netherlands and at UU. They were also asked whether that feeling has changed recently and if the political debate about the internationalisation of higher education affects them. The respondents were also asked to share their views in open-ended questions. DUB will soon publish a follow-up article delving into UU's results.