International graduates living in the Netherlands long-term

‘It's a nice country to live in, but you have to fight to make it here’

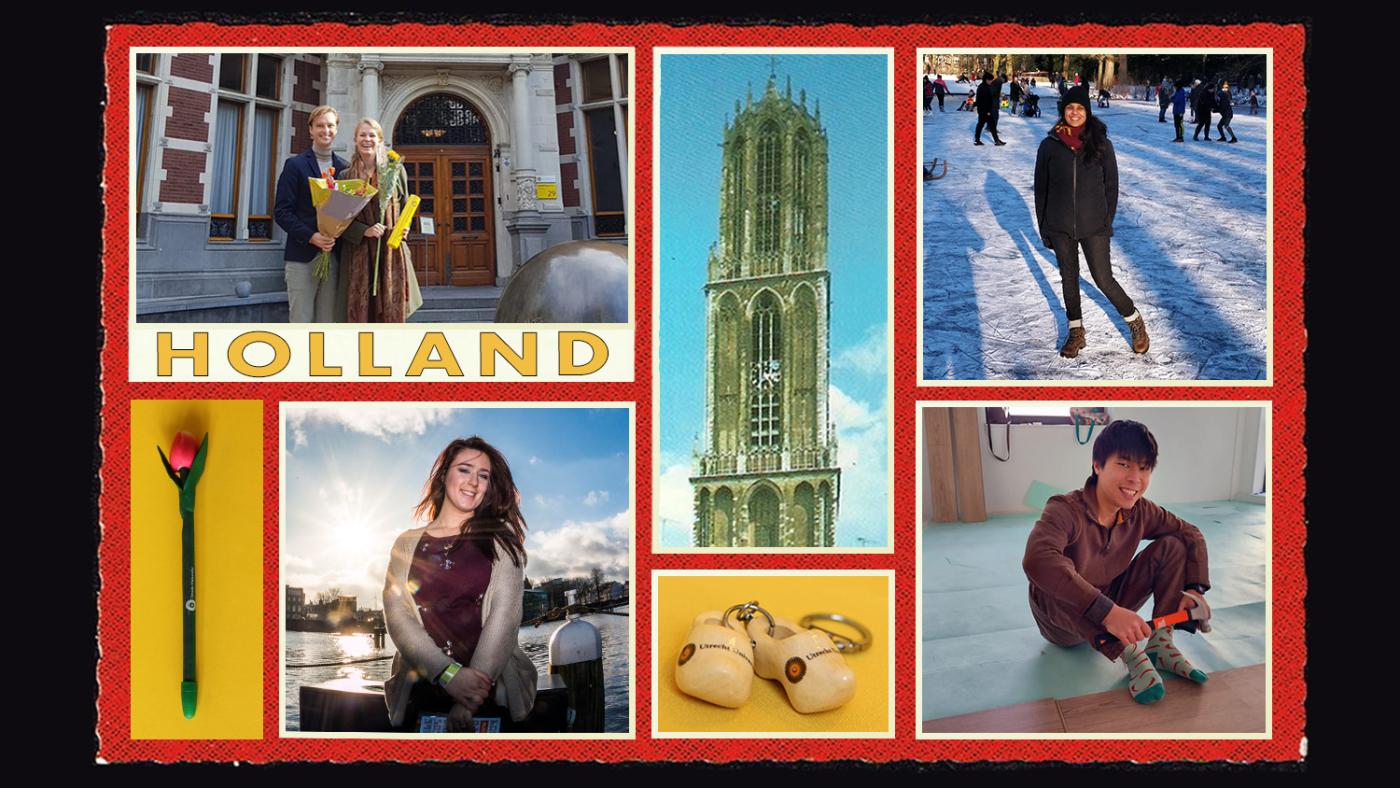

On average, 24 percent of international alumni still live in the Netherlands five years after graduation, according to Nuffic’s latest report on the topic, published in December 2023. They have many reasons to stay, such as work-life balance, good infrastructure, and cultural values like individuality and directness (see box below). DUB met four people who are still in the Netherlands five years or more after obtaining a diploma from UU.

“It’s a misconception that it’s easy to find a job”

Lina Marcussen comes from Sweden. She moved to the Netherlands in 2019 to pursue a Master’s in Social Policy & Public Health at UU. She made that decision after starting a relationship with a Dutch guy she'd met while on exchange in South Africa.

Marcussen was strategic in her choice of Master's. She went for a Master’s degree with an internship period so that she would have a foot in the door of the Dutch labour market. “Unfortunately, the company didn’t have a position available by the end of my internship, so they couldn’t hire me.”

Finding a job without any connections and without speaking the language fluently was “pretty difficult”, she recollects. “It depends on the field, of course, but there is this misconception that it's easy to find a job that does not require speaking Dutch. In reality, very few employers would take you.” No wonder most of her international peers have left the country by now. “Of the 30 internationals in my class, only two others are still here. The rest couldn’t find a job.” According to Nuffic, more than 50 percent of graduates from abroad leave the Netherlands because they can’t find employment.

To increase her chances in the labour market, Marcussen took a one-year Dutch course offered by the municipality of Amsterdam, where she used to live. She also practised a lot with her partner and his family. Eventually, she landed a job in marketing, later transitioning to her field of choice: startups. Today, Marcussen works as a startup scout at UtrechtInc. “I would recommend staying here, but it takes hard work,” she concludes.

Now married and a mother, Marcussen doesn't discard the idea of returning to Sweden someday. She misses being able to take a stroll in the woods without seeing anybody else. "The Netherlands is pretty crowded," she says. In addition, the social security system in Sweden is more family-oriented. "But, for now, I am happy here."

“Sorry, we can’t hire you”

For graduates from countries outside the European Economic Area (EEA), the pool of jobs that would take them is even smaller. “It took me a while to convince someone to go through that extra effort to hire me as a student,” says Matthew Tan, from Malaysia, who has been here since 2015.

He started as a Liberal Arts & Sciences student at UCU and then studied Medicine at UU. “There were a lot of part-time jobs I really wanted, but couldn’t get. They just kept on saying: ‘Sorry, we can't hire you.’ That can be quite annoying. You don’t fit the system.” In the end, persistence paid off and Tan scored a job as a teaching assistant for a global health course when he was at Med school.

After graduation, more barriers await non-EEA alumni looking for a job. These graduates can apply for an additional year in the Netherlands (the so-called Orientation Year or Zoekjaar) during which they are allowed to work anywhere. However, this visa cannot be renewed. After that year is over, they can only stay in the Netherlands if a company applies for a highly skilled migrant visa on their behalf.

There is a catch, though: most companies are not allowed to do that. First, they must acquire a permit to act as sponsors – a costly procedure unless the business hires non-EEA foreigners regularly. That’s where a lot of talent falls through the cracks. According to Nuffic, 6 out of 10 non-EEA alumni leave the country because they can’t secure a visa.

Like Marcussen, Tan worked hard on his Dutch skills. Getting the necessary exposure was a challenge. “At UCU, everyone speaks English and Dutch courses are quite expensive,” he explains. The solution: going to Belgium, where Flemish courses are subsidised. By the time he applied to the Medicine programme, his Dutch skills were good enough to get him through the admissions process. However, following the programme in Dutch afterwards “was like studying with a handicap. In the beginning, I didn’t get everything that was said.” The Covid-19 pandemic, which hit by the end of his second year, worked in Tan’s favour. “All lectures were taped, so I was able to move at my own pace and rewatch some of them.”

Today, Tan works as a junior lecturer at the Department of Anatomy. He has lived in the Netherlands long enough to qualify for permanent residency, which means he now has the same working rights as Dutch citizens. He has a Dutch girlfriend and he feels like part of her family. He doesn’t think he will be moving back to Malaysia – or anywhere else. "Career-wise, that just wouldn’t make sense. I’ll probably remain in the Netherlands all my working life. I’m building a pension here!”

“Sometimes, I feel very alone in this country”

Even when non-EEA graduates do find a company willing to sponsor a highly skilled migrant visa, their stay is entirely dependent on their jobs. If their contract doesn’t get renewed and they don't find another company to sponsor them in time, they must leave the Netherlands in just a few weeks. This uncertainty caused Juhi Nagori a lot of stress.

Nagori comes from India but grew up in Kenya. She moved to the Netherlands 12 years ago to study at UCU. She also did a Master’s in Meteorology & Air Quality at Wageningen University and a PhD at UU, which she didn’t complete. “I used to think: ‘If I do something wrong, if I miss a deadline, I’ll be forced to leave everything behind,’” she says about the time she had a highly skilled migrant visa. She is a permanent resident now, but it took her seven years to be eligible for it. “Seven years of thinking I could be leaving at any point.”

In addition to the stress caused by visa procedures, Nagori underscores loneliness as a factor driving many international graduates away. “Sometimes, I feel very alone in this country. When I left UCU, I was quite surprised at how difficult it was to get to know Dutch people."

Moreover, Nagori notes that most internationals end up leaving the Netherlands at some point, which requires those who stay long-term to continuously work on making new friends. Loneliness hit her particularly hard during Covid, when she didn’t have any family members or lifelong friends around. Still, she has managed to meet “some great people” that she wants to “keep in her life”. One of them is her partner, who is Dutch.

Language remains challenging for her. “I think my Dutch is good enough for working, but sometimes I still struggle a bit with socialising.” To accelerate her learning process, Nagori took private lessons and only applied to Dutch-speaking vacancies after her PhD. “I worked only in Dutch for a year, which forced me to speak the language.” She currently works as a Climate Risk Modeler at Royal HaskoningDHV, creating datasets about the risk of climate hazards. A bilingual position.

Nagori has no trouble imagining herself elsewhere, but packing her bags is a whole new ball game. “I could see myself living anywhere, but I don’t feel like putting in that kind of effort anymore. It’s a lot of work.” Chances are she will remain in the Netherlands for many years.

“This is where I feel most at home”

Kegan Sweetnam is originally from South Africa but grew up in the UK and Belgium. She is an exceptional case as it’s been smooth sailing for her since graduating from UCU in 2013. Sweetnam took a gap year to acquire some work experience, planning to pursue a Master’s in Criminal Law afterwards. In the end, she never went back to studying. Hired by a Japanese automation company as a legal assistant, she was asked to take on a role in a Project Management Office within the IT department one year later.

Today, she works at a Dutch consulting firm helping build offshore wind and solar farms. “I feel very accepted as an international, almost wanted,” she says. According to Nuffic, Sweetnam is an exception because international graduates who have a Master’s degree are more likely to find a job than those who don’t.

She never struggled with visa impediments because she has British citizenship. “It only got a bit annoying after Brexit,” she says. "I am going to become Dutch as soon as I possibly can."

Learning Dutch wasn’t too hard for her, either. Sweetnam went to high school in Belgium, where she took German as a second language. Additionally, her mom speaks Afrikaans. “It’s all very similar,” she explains. That’s why she never took a Dutch course. “I learn best when I’m thrown into the deep end." And thrown into the deep end she was, when she got into a relationship with a Dutch man whose family does not speak English. They are now married and have a child.

Sweetnam can no longer imagine herself living anywhere else. “I love working with different cultures, but this is the one I identify the most with. This is where I feel most at home.”

What makes international graduates stay in the Netherlands?

There are many factors leading them to stay. Work-life balance was mentioned by over 80 percent of graduates heard by Nuffic, as well as by Marcussen, Tan, Nagori and Sweetnam. The Dutch are not keen on working overtime without a good reason and they value the time they spend with their families. "That's definitely a big pull factor," says Tan.

Quality of life was also mentioned by over 80 percent of respondents in Nuffic's research. "Things just work here. The infrastructure is good," says Nagori.

Having a romantic partner helps a lot, too. All four alumni we spoke with are in relationships with Dutch people. In Nuffic’s research, 55 percent of stayers indicate that having a partner in the Netherlands has been extremely important in their decision to stay.

Cultural values such as directness and individuality play a role too. “I very much like the freedom I have here to be what I want to be and do what I want to do. The culture I come from is a bit more conservative,” says Nagori. “I am unusually direct for a Malaysian. I love that I’m allowed to get away with it here,” observes Tan. “The Dutch are very to the point. If they don’t like something, they will tell you. In Britain, it’s all about being polite and beating around the bush,” Sweetnam adds.