UU Rector wants to take university democracy to another level

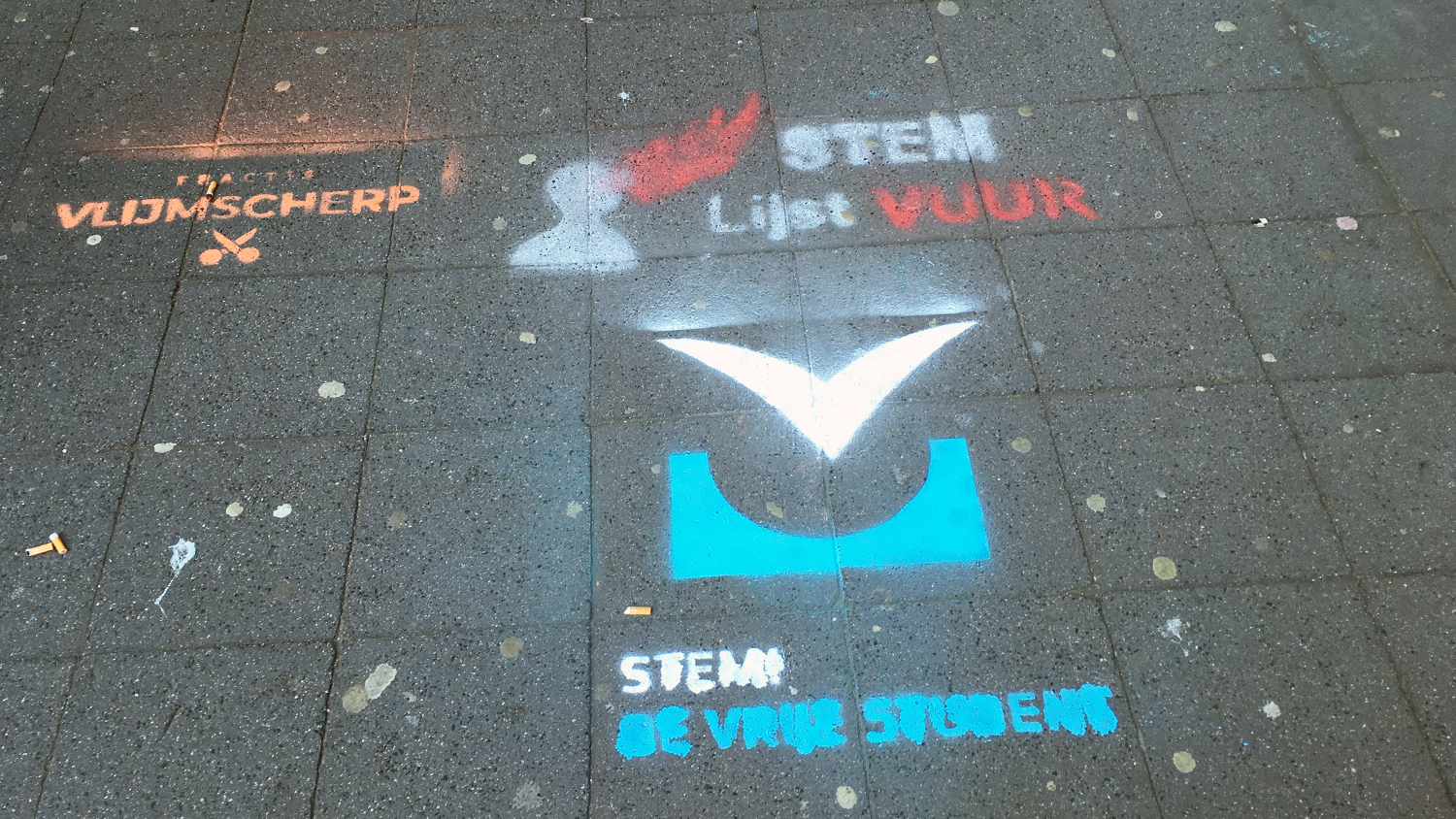

The number of parties has been growing in the university in recent years. There are currently six of them in the University Council – three comprised of students, two of employees, and one with representatives of both groups. Although the parties don’t differ much from each other, the differences that do exist are often emphasised or referred to with ferocity in discussions about topics such as proctoring, diversity, and workloads.

The parties have also been using DUB more often as a platform to share their opinions. UUinActie, for example, has recently called for a democratically-elected rector and student assessor in the university board. Recently, parties have also manifested their opposition to collaborations with universities from countries that are not democratic, or where democracy is under pressure.

Rector Henk Kummeling has noticed this trend in the university’s codetermination bodies. “I haven’t done any research on it, but if you look at national politics, you’ll see a similar movement. Politics in the Hague is becoming more and more fragmented, and you see more and more identity politics: it’s not about being right, but about showing who you are. The same is happening in the University Council, where I’ve been seeing the positions harden, while we have to reach compromises and achieve things together.”

To him, the worst thing about this phenomenon is that it feels like there’s insurmountable distrust in the air. “It is as though you’ve got a secret agenda, or you’re trying to get something done through sneaky tactics. Of course there should be critical questions, a certain amount of distrust is healthy, but if you take it too far, it’s counterproductive. I don’t like the feeling that gives me.”

Student input most valuable when administration is transparent

Kummeling has a lot of experience with codetermination, democracy, and running an administration. When he was a law student in Nijmegen, he served two years in the faculty council, and one year as student assessor in the faculty board. His career started in the same university, as teacher and researcher of constitutional and administrative law.

Later on he became professor in the same field in Utrecht, where he obtained the position of Dean of the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance in 2008, and Rector of the university ten years later. Between 2005 and 2016, Kummeling was the Chairman of the Dutch Electoral Council, an independent administrative body that advises the government and parliament on matters concerning elections and the right to vote. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that his interest in codetermination at the university is higher than average.

“If you want all relevant parties to participate in the decision-making process, then there’s still a lot to be done” is his conclusion about the way codetermination works at Utrecht University. For example, he welcomes the idea of adding a student assessor to the Executive Board. “Students come up with topics or perspectives that administrators sometimes don’t think of. Their input can improve the decision-making process, and thus increase the support for a decision.”

However, the rector stresses that input from the students is most valuable when it’s as well-informed as possible, which is why boards should work in a transparent manner. “We’re soon going to make the reports about the Executive Board meetings public, for instance. That doesn’t happen yet, even though we don’t see any reason to be secretive about these meetings.”

In addition, not all boards within the university work with the student assessor as transparently as the rector would want. “I had a second meeting with all student assessors in October, and I noticed that some of them participate in every meeting of the faculty board, while others only join a few.” He wants to talk to the deans to find out why this is, and how attendance can be improved.

Programme committees are another place where Kummeling sees room for improvement. He says they need to be well-informed to be able to evaluate the quality of a curriculum. “But I’ve been hearing that not all committees are sufficiently informed and supported,” he explains. Faculty councils could also benefit from more transparency, in the rector’s view. “How public are their meetings? As a university, we’ve got values that we should represent, such as transparency and openness.”

Students’ influence would increase with a two-year term

Furthermore, Kummeling thinks that the quality of students’ input would increase if students would spend more than one year serving as assessor to the Executive Board, or in the University Council. Currently, students put their studies on hold for a year to dedicate themselves to these activities. Members of other codetermination bodies do their work alongside their studies.

“Students who join our codetermination bodies will always have an information deficit. It takes a long time to get the members up to speed with everything. The budget, for example, is always complicated to understand. By the time they’re settled in, the year’s almost over. We also get the same questions every year – about a second chance to improve their grades, for example.” A longer codetermination period would, in the rector’s view, give students the opportunity to acquire more knowledge about how the university works, which would enable them to provide better input. “I spent two years on the faculty council and one year working as student assessor. That was enough time to figure things out.”

This isn’t the first time that someone suggests students to serve two years in the council – the same period as employees. The rector thinks it’s perfectly possible for them to combine their codetermination work with their studies. “That way, they can help us with real issues and strengthen their influence in relation to the board and staff members.” Another option is to switch half the members every two years. “Then you can build an institutional memory. If students spend more time on the council, they have a better idea of what’s been done in previous years, so they will not ask the same questions year after year. This would also enable them to delve deeper into subjects and possibly bring forth better arguments to change regulations.”

Rectors don’t have enough power to justify an election

One of the most frequent suggestions voiced by students and employees within the codetermination bodies is that faculties, departments, and study programmes should have the freedom to decide more things for themselves, which would make the university more democratic. Kummeling isn’t so sure about that. He thinks decentralisation would make for some impracticable situations in the university, and wonders who would benefit from such a change. “Sometimes, countering inequality requires a decision at the highest level. In our educational model, for instance, students are allowed to take courses from other study programmes. What if a programme suddenly decided that they don’t want to participate in this? Or what if some programmes would do proctoring and others wouldn’t? What would that mean for students?”

Another recurrent idea is to hold elections for positions such as that of the rector or the student assessor. Elections for other bodies, such as programme committees, don’t take place at UU either, even though they are allowed. Once again, the rector disagrees. “Having elected members for a job doesn’t guarantee more democracy per se,” he ponders. “Democracy isn’t just about majority rule. True democracy means taking minorities into account when making decisions; it’s about having codetermination by your side throughout all stages of the decision-making process.”

For Kummeling, a democratically-elected rector is a no-go, although he’s happy to discuss the subject with the codetermination bodies. “I just think elections should only be held for jobs with actual powers. I don’t think electing a mayor or a rector is a good idea. A mayor only has authority over public order, really: the municipality is actually governed together with the aldermen. In our case, the university board consists of three members who have to make decisions together. The rector can’t decide anything by himself. If the rector was like the American president, someone with the power to make decisions by himself, then things would be different.”

In addition, Kummeling is afraid that an elected rector would cause division at the university. “Quite a few rectors of Flemish universities told me that there’s a division there between supporters and opponents of the rector. So, before they can work on their actual agenda, rectors first have to calm things down.” What about electing all the members of the Executive Board? “That’s an interesting idea, but it would make things even more complicated. It’s almost undoable.”

Even though there are no elected rectors in Dutch universities, a rector’s position becomes practically unsustainable if the codetermination bodies aren’t happy. “In order for me to serve a second term as rector, that needs to be approved not just by the Supervisory Board, but also by the University Council. If they don’t want me there, I’m out. It’s as simple as that.”

UU’s collaboration with other universities is under scrutiny. Recently, the University Council asked the Executive Board to take action against China, Hungary, and Belgium – China for its violation of human rights, Hungary because of the president’s interference with universities’ codetermination and the active move to kick out an American university out of the country, and Belgium because their universities have introduced hijab bans.

How does the UU deal with universities and countries like these? Kummeling replies: “When it comes to collaborations within international networks and universities in our student exchange programmes, academic freedom needs to be guaranteed or we will not work together.”

“It’s a different story, however, when we’re talking about universities in countries where there’s an authoritarian regime. We work with them, too, but for different reasons. Universities there want to work with us to fight for more academic freedom and academic values. We’ve helped them enormously by keeping in touch with them.

“We collaborate, for instance, with universities in Indonesia and South Africa. We did so even when Indonesia was under Soeharto’s authoritarian regime, or when apartheid still existed in South Africa. For example, I am connected to, and Utrecht works with, the University of Western Cape, where many new ministers and leaders came from when the apartheid regime was overthrown and Mandela became president. As for Indonesia, when they needed new people for the new judicial powers, positions such as that of the ombudsman, or the human rights committee, went to people with whom we had collaborated, or who had been educated by Dutch universities.

“It’s easy to say that we shouldn’t have anything to do with China because of Xi Jinping. We do have to be very careful in building and maintaining relations, we shouldn’t be naïve. But, as a university, we’ve also got a universal value and meaning to observe. So, if we can help them in promoting academic freedom, we should.”