UUers: unintended consequences of rules are source of institutional racism

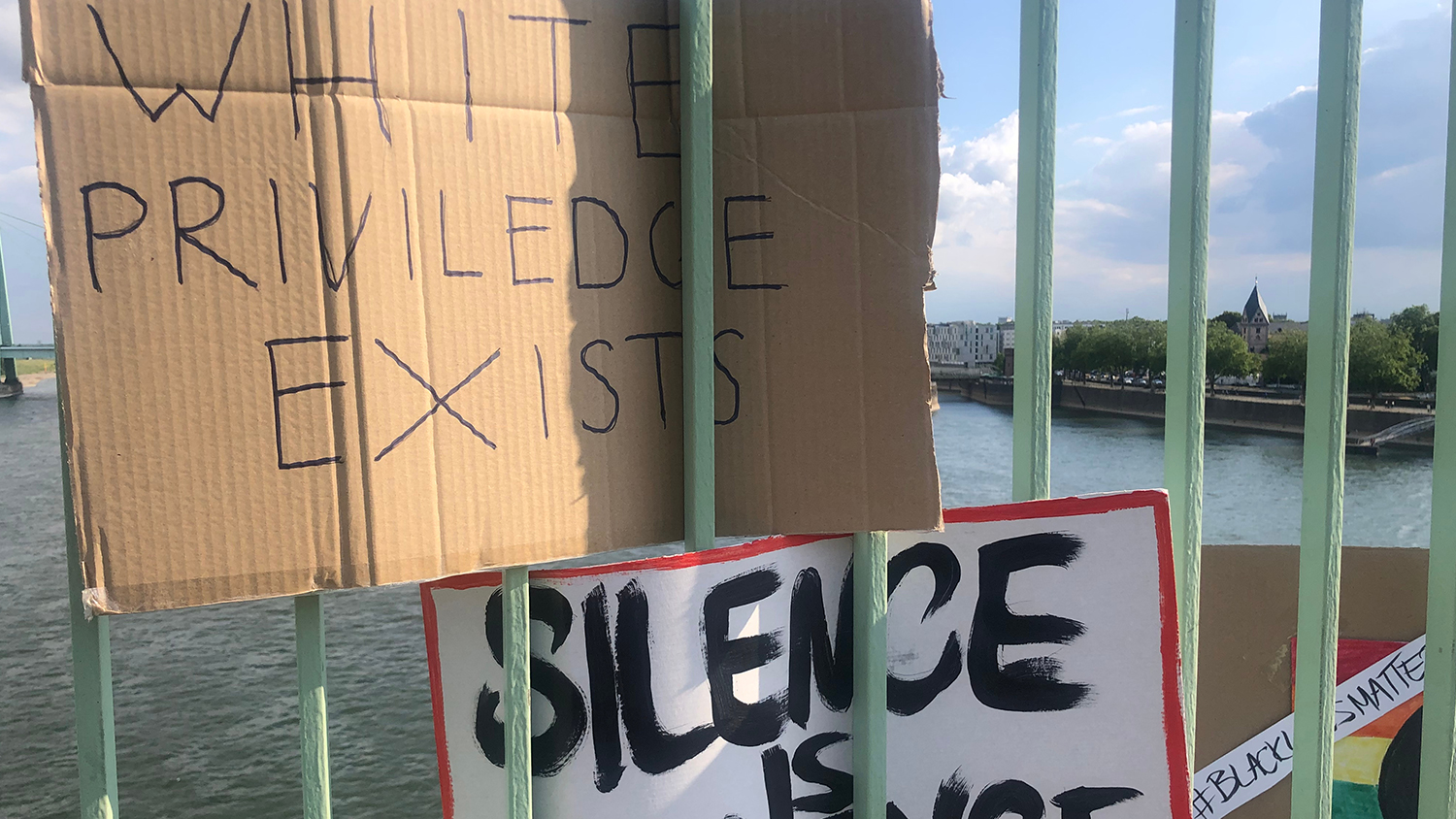

When George Floyd was killed during an arrest in the US this past May, the Black Lives Matter protests started. This made the racism debate resurge. At the UU, the debate returned from never-really-been-gone, and DUB, too, published a high number of stories and opinion pieces. They show how sensitive the theme of racism is at the university.

In those stories and opinion pieces, the term institutional racism was used frequently. But what does this form of racism entail? DUB consulted numerous UU academics to find out whether they can reach a uniform definition of institutional racism, and whether they can explain how it manifests at Utrecht University. This is the first article in a series of stories about discrimination in relation to the UU, which DUB will publish in the coming months.

A lack of awareness of the consequences of rules

Everyone agrees that intentional racism, meant to hurt and exclude, should be prevented and condemned. But the real issue lies deeper: do we have a privileged system? And if so, who’s to blame for that, and does the UU have a system like that, and does that mean there’s institutional racism, then?

Marjolein van den Brink is connected to the Netherlands Institute of Human Rights (SIM) and is a teacher at the department of International and European Law. She does research on issues related to equality, marginalisation, and exclusion. She words it as follows: institutional racism is the disproportionate disadvantaging of a certain population group through written and unwritten rules. That doesn’t necessarily have to be a conscious process.

Marjolein van den Brink is connected to the Netherlands Institute of Human Rights (SIM) and is a teacher at the department of International and European Law. She does research on issues related to equality, marginalisation, and exclusion. She words it as follows: institutional racism is the disproportionate disadvantaging of a certain population group through written and unwritten rules. That doesn’t necessarily have to be a conscious process.

“Sometimes, the cause is a lack of awareness of the consequences certain rules have,” Van den Brink says. “Language requirements, for instance, or the expectation that you have an x number of years of experience before you’re hired for a position. Those rules aren’t unjustified in themselves, but do affect different population groups in different ways.” So when does institutional racism play a role in a rule? That depends on the context, Van den Brink says. “You have to differentiate between intended and unintended consequences of rules. If the difference between them is larger than can be reasonably justified, something’s wrong.”

The discomfort of having an exceptional position

Institutional racism is hard to recognise, says Matthijs Kuipers, teacher at the department of Political History. “As a white man, I myself am not always able to do so, but by listening to what others are saying, you can see that it’s there. Students and teachers are evaluated on a certain idea of what makes a good student or a good academic. But because minorities aren’t as well-represented among students or teachers, that idea is rather one-sided. They’re less often given the benefit of the doubt.”

Professor Berteke Waaldijk, a historian who’s specialised in interdisciplinary gender studies, calls this the phenomenon of ‘mutual recognition’. “An institution isn’t just a sum of a set of formal rules. At a university, people meet each other in the roles prescribed by the institution, such as teacher, professor, or student. The more you feel at home in a role like that, the further you can get: you’re given the opportunity to show how good you are, and those ‘above you’ recognise themselves in your talent, and will encourage you.” When the role of skin colour, class, and sex is forgotten in this process, institutional racism surfaces. “When teachers and professors don’t explore the discomfort that comes with having an exceptional position – the wondering of whether you belong here – the institution will simply clone itself,” she states. “Only talent that looks and behaves like the ones who are already further in their career, will get opportunities.”

For that reason, Waaldijk says, teachers and researchers and administrators who themselves aren’t minorities should wonder a little more often why they were once noticed and encouraged themselves. “Was it because they had a creative mind and worked hard? Or – to use myself as an example – did the fact that I felt at home play a role? Both of my parents went to college, none of my family members have ever lived in an asylum seekers centre, my brothers were never racially profiled, and at 17, I already knew I had to say ‘lecture’ instead of ‘class’ [in Dutch, ed.].”

Marjolein van den Brink also sees that the issues surrounding institutional racism can be found in reality – in recruiting new academic employees, for example. “Still, very few Dutch people from a migrant background are hired. Research shows that in job interviews, we tend to choose the candidate who resembles you most. If two candidates are equally good, and you’re white, you’ll probably choose the white candidate. They’ll say: ‘The other one isn’t the best candidate’. But it’s never obvious who is actually the best.” There is no true racist approach behind it, she says. “We all have unconscious biases.”

Globalisation disadvantages Dutch people from a non-western background

Matthijs Kuipers studied the so-called Home-colonial culture, the way in which people in the Netherlands regarded the colonies. “The denial, both then and now, is recognisable. People are instantly on the defensive when talking about racism. But if people don’t want to talk about it, something more is at play. Refusing to do research, refusing to look at possible improvements, and refusing to be critical – that’s already institutional racism.”

Marjolein van den Brink says it’s certain there isn’t enough awareness at the university about institutional racism. “When we talk about discrimination, people think about diversity, first. And then, in the same breath, they think about internationalisation. But the students from other countries, including the non-western ones, are usually cosmopolitans. They’ll find their place. The people that fall by the wayside are the Dutch people with a non-western background. Globalisation disadvantages them.”

She resents that the university talks a lot about diversity, but doesn’t act on it. “The UU is an incredibly white university. If you look at how many young people from a different background graduate from havo and vwo-level secondary school each year, you’d expect the UU to be more diverse, too. But you can’t be certain about the cause of this. As a university, the UU should at least try its hardest to prevent any hidden obstacles. Just saying that people from a diverse background should apply for jobs, or register for study programmes, is too lazy.” Different recruitment and different role models could help in this, she thinks. “Don’t just emphasise the drinks.”

The whiteness of the university is not in line with the city

Marijke Huisman, who studies (among other things) the way the Netherlands deals with its slavery past and teaches Public History, Education & Civic Engagement, sees this too. “The whiteness of the university is not in line with the city. There’s no conscious policy of discouragement, but non-white young people aren’t knocking on our door, especially in my faculty (Humanities, department of History and Art History, ed.). But history and languages aren’t disciplines you study to get ahead in the world. Newcomers don’t choose these disciplines.” One remarkable thing, according to her, is that other universities – like the VU in Amsterdam and the Erasmus University in Rotterdam – are much more diverse. “That’s partially due to their study programmes, but also because of their connection to their cities, and in the VU’s case, its religion-friendliness.”

Moreover, the students of colour who do come here, often have a hard time, says Marjolein van den Brink. She explains that law students receive study advice in their first year, after which many students drop out. For years, practice was to then redivide the remaining students into groups based on their acquired ECTS, in order to thereby praise motivation and work. “Students from a migrant background tended to be in the bottom two groups exceedingly often. But these students were also the ones who, more than average, came from a university of applied sciences,” Van den Brink says. “The best students often come from a certain class background. What people bring with them in terms of baggage, self-confidence, and what you’re allowed to ask – at Law, these do tend to be the blonde girls. If you stand out because of your skin colour and culture, and it’s hard for you to find a room, for instance, it doesn’t really contribute to becoming the best student of the class.”

What’s the centre of the world for history?

At History, too – the course that’s particularly focused on critical thinking about stories – there’s a form of institutional racism in the curriculum, Marijke Huisman thinks. “What’s the centre of the world for our discipline? It’s still all too often Northern Europe, or the transatlantic world,” she states. “What does that mean for our worldview? And for what we decide are good historical sources? Not all groups of people are represented equally in the archives in which historians often find their documents. First-year students do take a course about world history, but it’s separate from the curriculum.” These types of questions, Huisman says, are important to all historians. “We shouldn’t box people in on their colour.” She’s happy, therefore, that the theme of racism is more and more alive among students in the lecture halls.

The four say more awareness on institutional racism is a start. That can be done through training sessions, or through work groups, like the Decolonisation workgroup at History, that reflects critically on the courses. But what has to change after that? They don’t entirely agree. More transparency in the recruitment process could help, Van den Brink says. She also mentions anonymous applications as an option. Huisman calls for an additional branch of the university in Overvecht. Quotas could also work, Matthijs Kuipers says. “But the Netherlands is allergic to quotas.”

Translation Indra Spronk