Veterinarians spent a long time fighting for their place in society

In the past few decades, the only university degree in Veterinary Medicine in the Netherlands has been more popular than ever. Every year, Utrecht University is forced to reject hundreds of applicants hoping to secure one of the 225 slots available. All graduates are able to find a job relatively easy and, after the Covid-19 pandemic, veterinarians' expertise is highly valued. The profession’s reputation is flying high.

However, things were quite different about two hundred years ago. Back in those days, those interested in getting an education in Veterinary Medicine had to go abroad. But things changed in 1821, when the National School of Veterinary Medicine opened its doors in Utrecht, initially as a "kind of glorified vocational course", in the words of Peter Koolmees, Professor Emeritus of Veterinary Medicine in Historical and Societal Context. The city of Utrecht was chosen due to its proximity to UU, as the university's professors could teach future veterinarians.

Peter Koolmees. Picture by Onno van der Veen

When the first graduates of the National School of Veterinary Medicine started looking for a job, farmers did not accept them with open arms. In fact, by 1850, the employment rate was so low that the government considered closing the school altogether because there were not enough students interested in enrolling in it. But, soon after that, a nasty disease emerged and those bookish scholars were able to control its spread, which improved their reputation significantly and guaranteed the continuation of the school.

It's a recurrent story: throughout the past two centuries, veterinarians' reputation increased more and more thanks to their role in the strive against contagious diseases, much like in the present day. "Yes, these are interesting times for the profession”, says Koolmees, who has no difficulty listing the diseases that contributed to boosting the image of veterinarians: rinderpest (also known as cattle plague) in the 19th century; tuberculosis, salmonella and mad cow disease in the 20th century; and bird flu, Q fever and Covid-19 in the 21st century. “Regarding the latter two, veterinarians have long warned about diseases that can spread from animals to humans, the so-called Zoonoses, but people didn't pay much attention".

A University College Utrecht avant la lettre

Alexander Numan is considered to be the founder of academic vocational training in Veterinary Medicine. Numan had trained as a general practitioner in Groningen and made his living as a country doctor. Interested in agriculture and animal husbandry, Numan was far ahead of his time, stated Koolmees in his 2007 oration. Numan argued that there was a need for an academic degree programme in the Netherlands, saying that would benefit society and contribute to the development of comparative medicine. Although Numan acknowledged that such an idea would face a lot of resistance, especially considering the low status of Veterinary Medicine at the time, he maintained that the scientific method was necessary to improve animal husbandry.

In order to provide the study programme, the government bought a bankrupt cotton printing factory on the grounds of the Gildestein estate, which was located on the outskirts of the city. “From the Poort building, you could see all the way to De Bilt”, says Koolmees. The country doctor was recruited as a professor to the first group of students, comprised of 24 young men who not only had classes at that building but also lived there. "A University College Utrecht avant la lettre”, compares the Professor Emeritus. They took inspiration from the French, who had founded the very first Veterinary Medicine School in Lyon in 1762. The school had a sort of caretaker to teach the students manners: in addition to the subjects required to become veterinarians, they were also taught how to speak correctly and were graded on their diligence and behaviour.

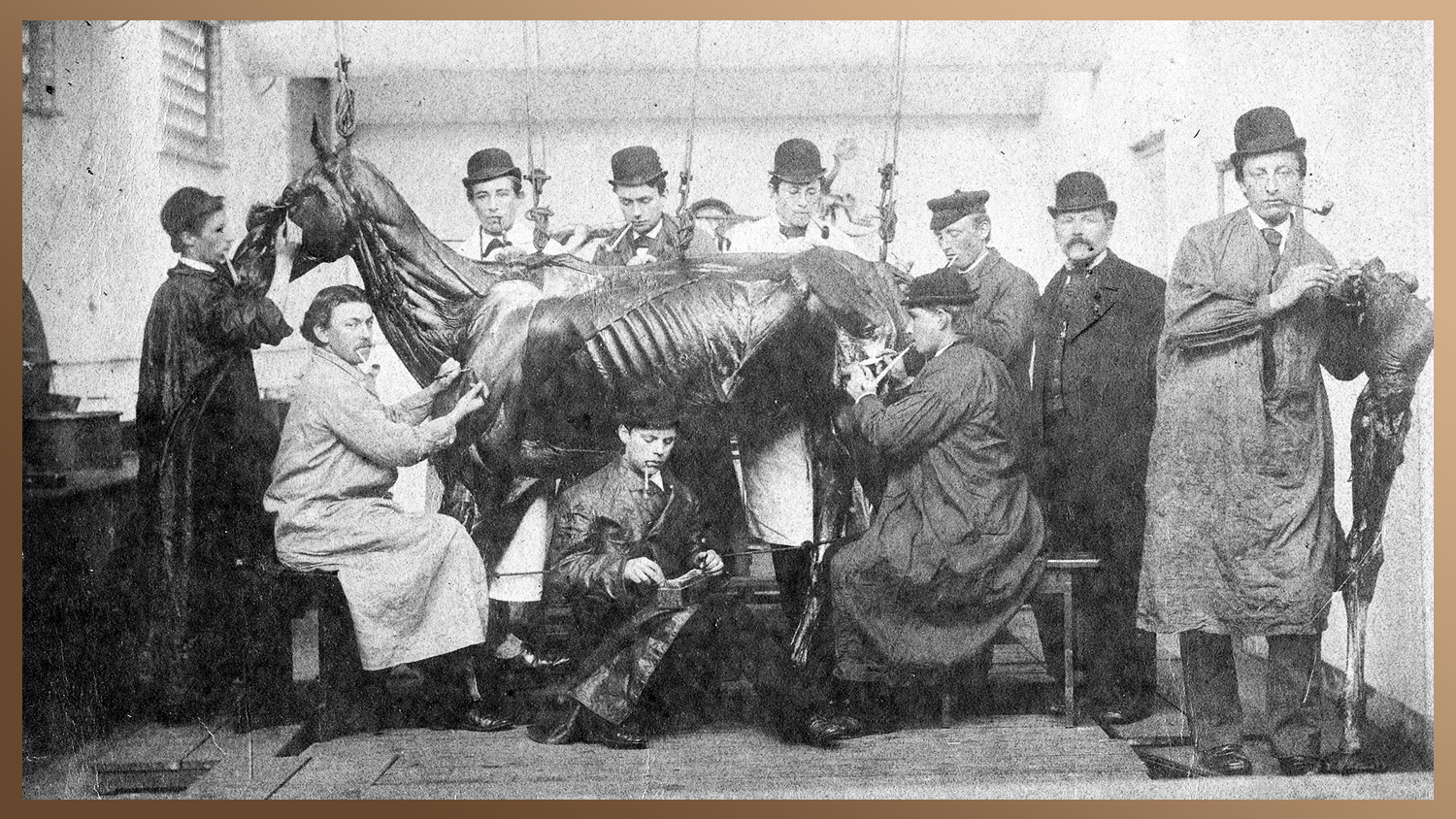

Group portrait of students being taught in the dissecting room. Photo: Utrecht University Museum

During those first years, most of the knowledge was passed on verbally from the lecturer to the student, as there were hardly any textbooks to rely on. For example, the students learned anatomy by dissecting cadavers. “That happened in the basement of the Poort building”, tells Koolmees. The concept of hygiene was very different back in those days: “Next to the building, there was a small river called the Biltse Grift, where the remains of the cadavers were dumped through a hatch after the dissections.”

The students also learned to make their own medicines. A part of the director’s garden was used as a medicinal herb garden for this purpose. There, students were taught about the different herbs, their uses, and how to make medicines with them.

Glanders in horses and rabies in dogs and cats

When they graduated, the first batch of students did not have an easy time. They had to compete with about six to seven hundred “cow obstetricians, horse doctors, shepherds, blacksmiths, women who were skilled in midwifery, and charlatans”, explains Koolmees. “All those people had practical experience. These ‘empiricists’ already had a foothold among farmers, so the added value of graduates with theoretical knowledge, who were known as 'government veterinarians', was not immediately recognised". Because the graduates hardly managed to establish themselves, no new students enrolled in the school.

The Dutch government considered terminating the programme, even though the school’s research had already yielded some new insights into public health. Between 1850 and 1860, the school catalogued parasitic diseases caused by tapeworms, for example. This led to the discovery that these worms can also infect humans through the consumption of meat, causing them to become ill. However, according to Koolmees, something far worse had to happen to save the programme.

“There was another outbreak of cattle plague in 1865, just like in 1813. This was an extremely contagious disease that spread all throughout Western Europe. The 'government veterinarians' introduced measures that require no explanation today: the cattle were quarantined, cattle transport and markets were prohibited, and infected cattle were culled”, reports the Professor. By the end of the 19th century, several vaccines had been developed to fight infectious diseases such as rabies, swine erysipelas, and sheep pox, which improved the standing of trained veterinarians. “Those guys in Utrecht really do seem to be a step ahead of the people who learned in practice”, is how Koolmees phrases the thought.

Thanks to the cattle plague, interest in the Veterinary Medicine programme was revived and the students moved to rooms in the city. The Poort building became too small, so new buildings had to be constructed in the green area between what is now Biltstraat and Poortstraat in the Wittevrouwen district. Education and research were still mainly focused on cattle, horses and dogs, animals that were in the service of humans in those days, by pulling carts or ploughs. “Glanders in horses and rabies in dogs and cats posed major problems”. However, in the 18th century, veterinarians turned their focus to pets as well, as animals were increasingly being kept as companions.

“Until then, veterinarians used to call themselves veeartsen (cattle doctors). In 1910, they started to use the name dierenartsen (animal doctors). They had already acquired a solid position in Dutch society by then”, says Koolmees. In 1918, the status of the National School of Veterinary Medicine changed. It became a university of applied sciences and was granted the right to confer doctoral degrees. It was not until 1925 that the school became part of Utrecht University as the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and the first female student, Jeannette Voet, enrolled. Before her arrival, people used to think that women were not strong enough for the profession, to say the least, but Voet – who would go by the name of Donker-Voet after her marriage – proved otherwise. Her arrival also led to a refinement in the men’s manners, which, the university concluded, was actually a positive development.

Analysts or researchers of Veterinary Medicine. Photo: Cas Oorthuis, courtesy of the Royal Dutch Society for Animals (KNMvD)

The “horse girl” phenomenon breathed new life into the equine division

After the Second World War, the faculty took a critical look at its programme. Industrialisation led to horses being replaced by tractors, which drastically reduced the number of horses in the Netherlands. However, the programme was still very much focused on these animals. The 1960s also saw changes in farming due to increases in scale and intensification of animal husbandry. Moreover, many people in the Netherlands no longer had to work on Saturdays and pets were no longer exclusively for the well-off, says Koolmees. The faculty’s discussion about the role of horses in the programme was still ongoing when, in the 1970s, horses also became companion animals. “The 'horse girl' phenomenon breathed new life into the equine division.”

In that same period, the number of students enrolled in the faculty increased. “In the 1960s, we suddenly had 280 applications”, recollects Koolmees. Women, too, were more and more interested in becoming veterinarians. What had started out as a male-dominated programme had evolved into a programme where women outnumber the men. Expanding the school on the Gildestein grounds, now also called Veeartsenijterrein, was no longer seen as a realistic option. Since the start of the programme, over a hundred years prior, the city had grown ever closer. From the 1930s onwards, local residents began complaining about the noise and the stench that came from the grounds. "Farmers would arrive early in the morning with lowing cows to have them examined."

Surgical operation of a dog circa 1938. Photo: Utrecht University Museum

At that time, the university already had two buildings in the Johanna polder, now known as the Utrecht Science Park: the Ruppert building and the Van Unnik building. Veterinary clinics were then built for the faculty not so far from these two university buildings. "They were the first to move in 1968", says the Professor. The last staff and students of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine left Wittevrouwen in 1988. “When I joined the faculty in 1973, I started working at the Utrecht Science Park, but a few years later, I was transferred to the Veeartsenijterrein. That was much more pleasant. The polder was quiet and the buildings were not very special. And the building where I worked may not have been very attractive – it was later demolished to make room for housing – but the atmosphere was much better.

That is why the incredible Dr. Pol is no longer considered a role model

At the Utrecht Science Park, the faculty was able to expand further. In addition to providing education and clinics where farmers, horse owners and pet owners can seek expert medical care, the faculty also set up an educational farm, De Tolakker, which allows students to learn first-hand how a farm works. There is also a lot of cooperation with medical professionals and scientists from other disciplines to improve the health of humans, animals and the environment under the name of One Health.

Anyone who still has doubts about the value of veterinarians need only think of the Covid-19 pandemic. Numan’s ideas are very topical once again. The farming of animals for human consumption, followed by massive increases in scale, led to diseases spreading within livestock populations and from farm to farm. Instead of focusing on cures, Veterinary Medicine increasingly shifted toward animal welfare and disease prevention. The time when veterinarians did not fully qualify as medical professionals is now long behind us, states Koolmees. “That is why the incredible Dr. Pol is no longer considered a good role model for our students. Nowadays, when an animal is in pain, the veterinarian first provides pain relief before they start the treatment. Dr. Pol is more of an animal mechanic. His methods are now considered truly outdated in the Netherlands.”

Looking to the future, Koolmees foresees more changes. The relationship between humans and animals has evolved and animal rights have increasingly become part of discussions on animal health and welfare. Thanks to the increased knowledge about diseases and how to combat them, and the advances in technology that allow animals to be fitted with artificial hips, for instance, the question arises of whether veterinarians should meet all the owners’ wishes. Another important topic, according to Koolmees, is the social discussion about animals in nature reserves, the circus and the zoo, and equestrian sports and keeping birds in cages. This discussion is also present in the faculty, which will face new challenges, in the view of the Professor Emeritus. “The influence of the rapidly changing relationship between humans and animals on Veterinary Medicine will yield plenty of topics for future research.”