Human Geography wants to restore its old thesis archive

‘Students' theses are valuable: they are free research’

Before 2008, Human Geography and Planning students had to submit their thesis on paper. They were all stored in large cabinets in the hallways of three separate floors in the Van Unnik building. With an average of seventy graduates a year, that piled up quite a bit. In the late 1990s, the programme started an archive.

It lasted until 2008 or so, when an inspection by the fire brigade came revealed that the cabinets in the hallway violated the fire safety code. Storing the thesis archive elsewhere was not an option, considering the already overflowing lecturers’ offices. The board then decided to throw out all the theses. The few theses that were still in the lecturers’ offices would find their way to the rubbish bin a few years later in the move to the Vening Meinesz building. Educational coordinator Erika van Middelkoop was involved in this process at the time. “At that time, no one batted an eye. But looking back on this, it wasn’t well thought-out. It’s an incredible shame that we didn’t realise at the time that for the historical record about geography, it was important to keep the archive.”

Grey literature

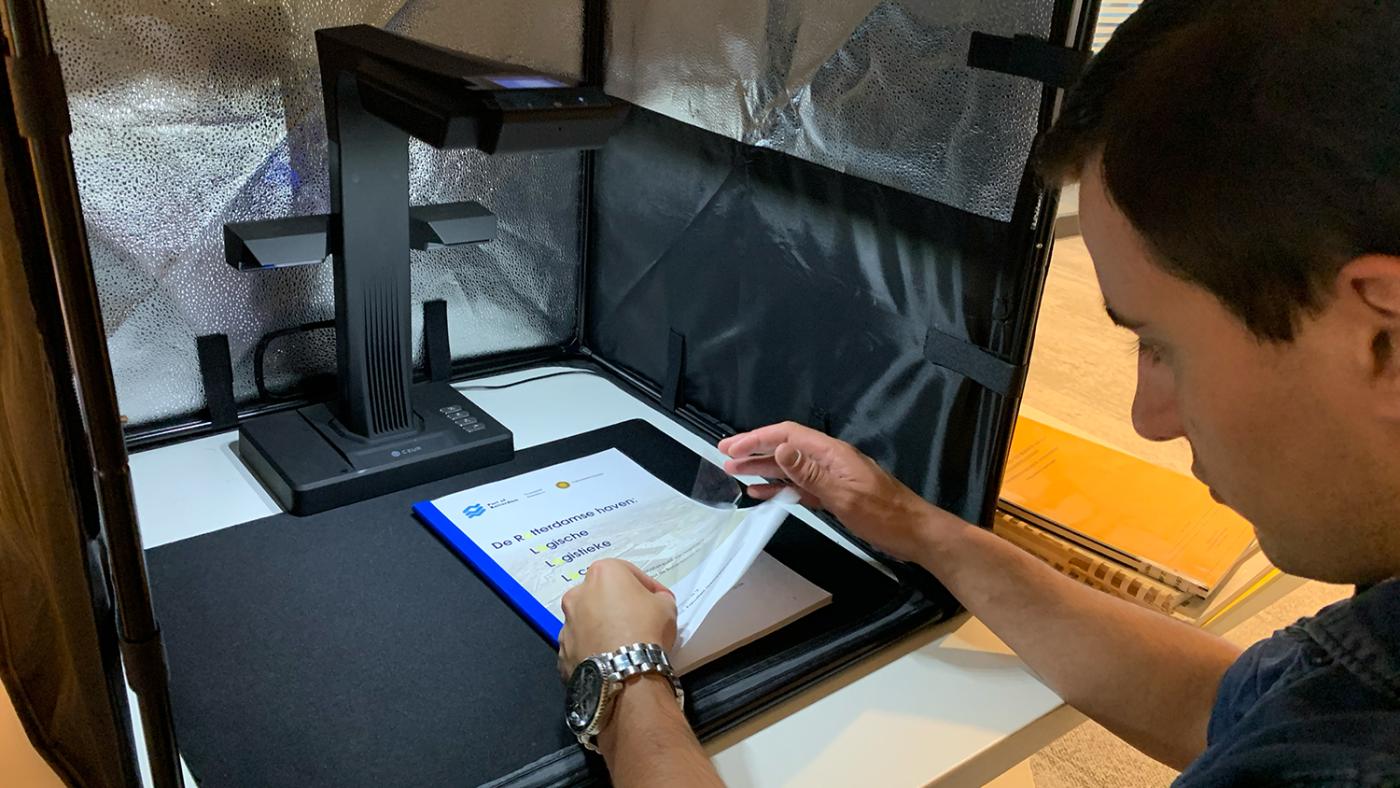

Times have changed. Digitising historical material has become cheaper and easier. Geography lecturer Michiel van Meeteren saw an opportunity to revive the thesis archive, with the assistance of the university’s Open Science Fund. Thanks to that grant, he could buy a scanner and pay a student to scan the paper theses. He recently put out a call to alumni to resubmit their theses (page in Dutch only, Ed.). That has already yielded several dozen works.

Van Meeteren wants to use the collected theses to create a digital map, on which you can search the location of the theses’ research subject. Current students can then, for instance, see whether there have been previous theses that were written about the same topic or location. But it can be interesting information for researchers, too, he thinks. For instance to find answers to contemporary issues. “We’ve had financial crises before, and there was a housing crisis in the 1950s and ‘60s too. How was that solved at the time? You’d have to dive into the studies that were done at the time. Including in student research, where you can find a lot of local and contextual information.”

A lot of scientists might look down on theses, but Van Meeteren does not. It’s in a category he calls ‘grey literature’, that wasn’t published in notable scientific journals. “They’re free research. Even though the supervisor can leave their mark on a thesis, you also see the vision and creativity of students reflected in them. They contain original data, because you have to collect your own data for your thesis. And there’s a lot of room to describe local nuances and local context.”

Michiel van Meeteren with hand-drawn maps and graphs. Photo: Amanda Verdonk

Changing themes

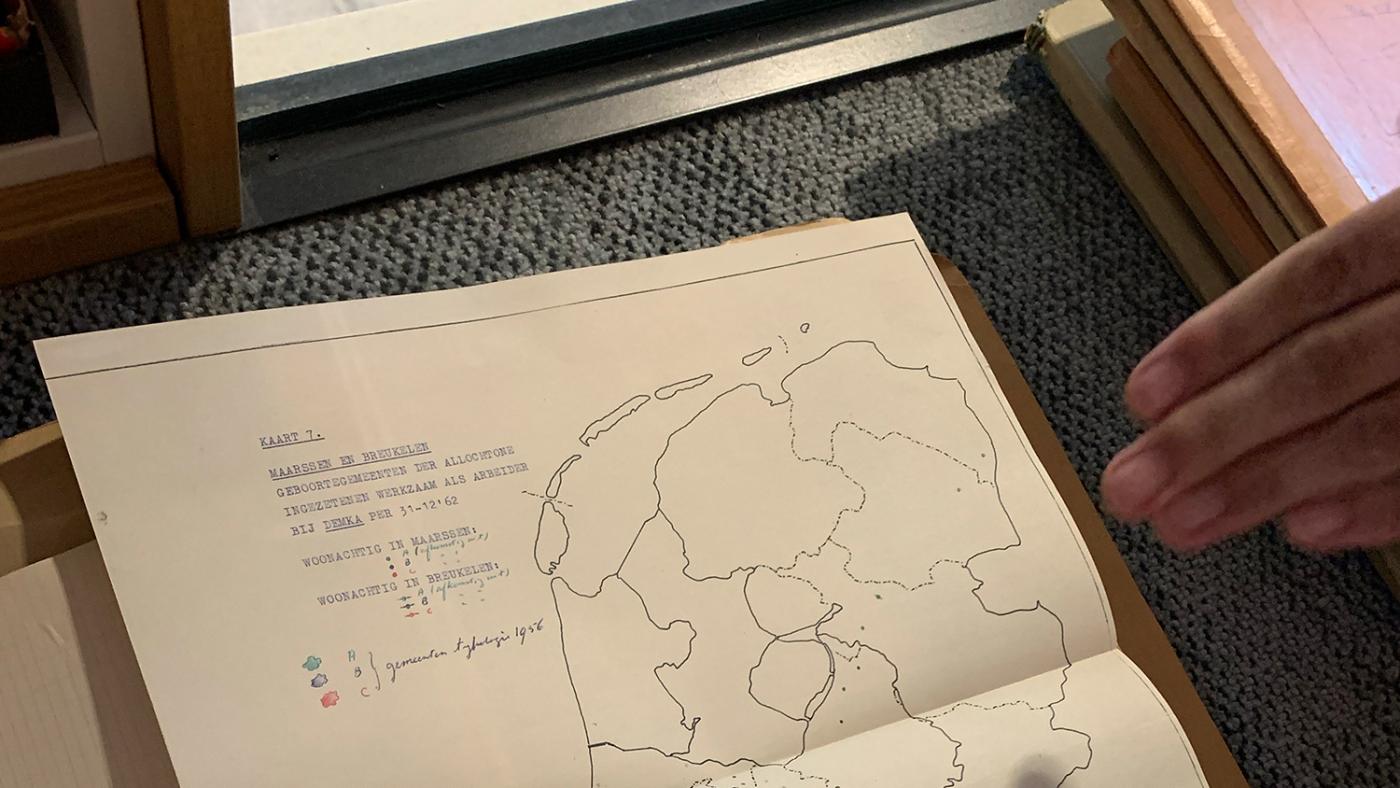

UU historian Mette Bruinsma is involved in the project, too. For her PhD research, she studied the complete thesis archive of the geography programme at the University of Glasgow, from the 1950s until now (2,600 theses). She will now use that experience to help Van Meeteren analyse the archive material. In Glasgow, she discovered a lot of personal stories and changing themes, which she also expects to see in some UU theses. “They’re all little portraits of what it’s like to be a geographer.” She saw, for instance, a change in skills throughout the years. “In the 1950s until the 1970s, you saw the most beautiful drawings, whereas drawing skills aren’t important at all now.” Van Meeteren recognises that from the UU theses and shows several older works that contain foldable graphs and hand-drawn maps.

Theses with hand-drawn maps. Photo Amanda Verdonk

Bruinsma also saw a slow change in the themes of geography education. “At first, there was a lot of regional research. Students had to collect facts about a certain neighbourhood or region: from demographics to soil condition. Later, research became more conceptual and thematic. Now, you either become a physical geographer, cultural geographer, or city geographer. That trend started earlier in academic research; education didn’t follow until fifteen, twenty years after.” That development is similar in Utrecht, says Van Meeteren, even if you can see that theses followed the memos from the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment for decades. Now, climate and sustainability are important themes, he sees. It’s possible the submitted theses will yield more interesting insight.

Bruinsma feels that universities don’t pay enough attention to this type of educational heritage, and she suspects the Geography and Planning programme isn’t the only one that was careless with its archive. “Academics should think about this more. It’s really a different type of information than state-of-the-art research, but that doesn’t make it less valuable.”

Affordable homes for sale in Nieuwegein (1985)

Constance Boogers. Photo: courtesy of Boogers.

Name: Constance Boogers

Graduation year: 1985

Thesis title: Living Costs in New Builds in Nieuwegein

Current position: Manager of information management at the Municipality of Nijmegen

“I did research with a fellow students on three neighbourhoods in Nieuwegein, on the affordability of homes for sale. We organised hundreds of surveys. We had to go door to door to spread them and return at a later date to get them back. In the university’s Calculation Centre, we could turn the survey responses into punch cards. Those were then read by the punch card machine, which spewed out thick piles of paper that contained the statistical outcomes. You could then go on the computer to turn those into pivot tables. Of course, we also had to draw our own maps and graphs, with special pens and sticky grids, a type of sticker with stencils and hatching. I also hand-drew the letters on the cover. My father worked for a publishing house, so he had a hundred copies of my thesis printed. I remember that I felt it was a special moment to put my thesis between all the other theses, in a room in Trans II (later the Van Unnik building, ed.). I still have a few copies in a bookcase between all my geography books. So I could find it easily when I saw the call. I can imagine that current students could still find my thesis useful, because the topic of living costs is, of course, still relevant.”

The music world of Utrecht

Sander van Lanen. Photo: Piet den Blanken

Name: Sander van Lanen

Graduation year: 2009

Thesis title: Promotion of local music in Utrecht

Current position: senior lecturer geography of inequality at Groningen University

“My Bachelor’s thesis was about the music industry in Utrecht. I did interviews at concert halls, record shops, and other music-related companies. I wanted to study to what extent there were local networks in which the separate music-related companies supported each other, and what role the identity of Utrecht played in that. At the time, I thought it was very exciting and challenging. I thought: who would take me seriously as a Bachelor's student? Writing it was a challenge, too. But I noticed that once you’ve done it a few times, you know what’s expected of you, and your self-confidence grows. The Bachelor thesis also sparked a passion for the discipline of human geography in me. That’s very useful, now that I’m teaching geographers myself. I did think it was a shame when I heard all the old theses were thrown out. It’s historic material that can show how a programme develops, and now that’s just gone. When I saw the call, I ran upstairs immediately and pulled all sorts of boxes from the cabinets. I was curious whether I’d be appalled at my writing style. Unfortunately, I only found a book with appendices, with the transcriptions of the interviews. I’ll have to take a look in my mother’s attic.”