Professor of Public Engagement wants UU to break all ties with fossil fuel industry

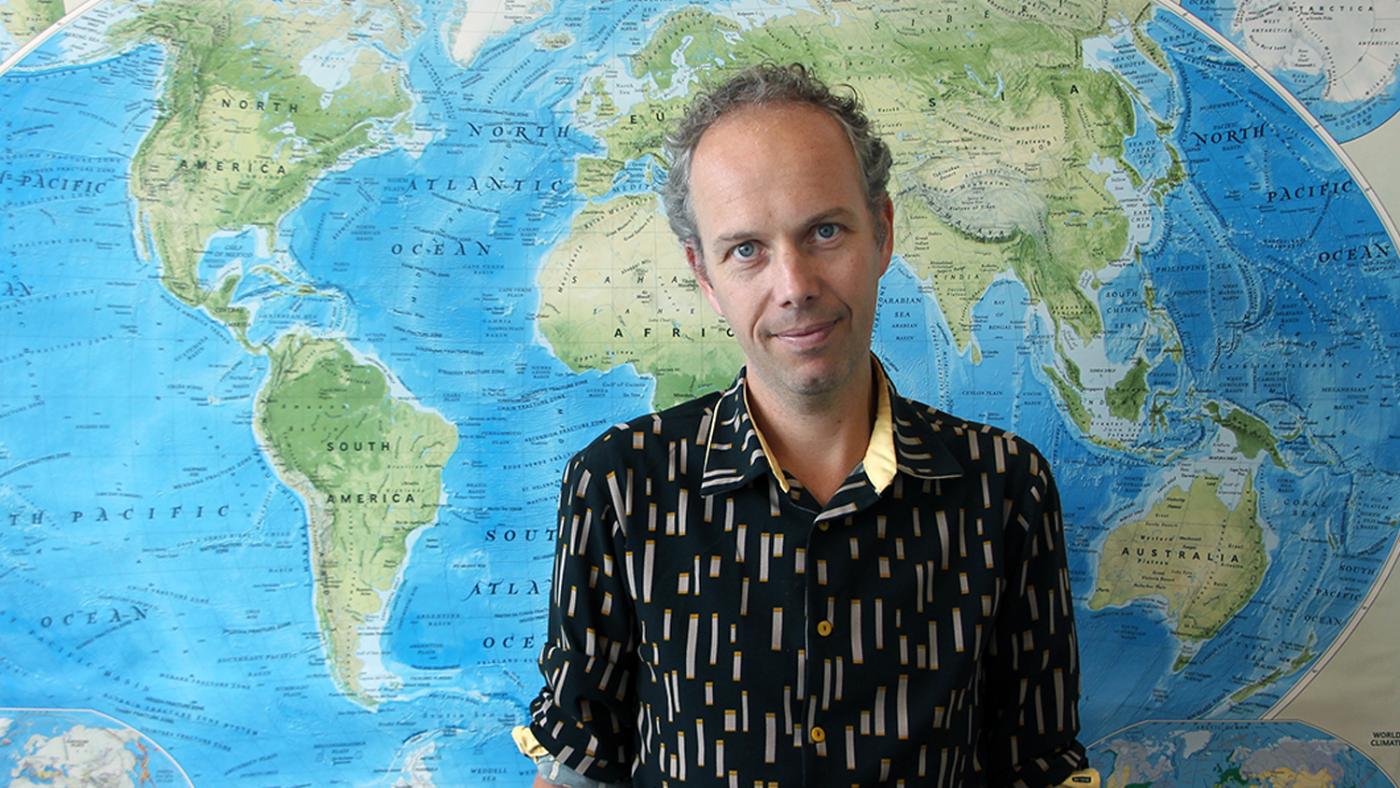

Erik van Sebille: ‘It's all about framing, scientists have to be more aware of that’

All eyes were on Van Sebille during his inaugural lecture last spring (link in Dutch, Ed.), when he described the effects that summing up climate issues in class has on him. His fiery speech calling for more collaboration between the public and academia stood out because he is also a Professor in Public Engagement at UU. “I’m an oceanographer and climate physicist but I also study how scientists should work in relation to society. When I was asked whether I wanted to become a professor in Public Engagement, I thought it was a great opportunity as long as I could combine it with my work as an oceanographer – and, luckily, that was possible. Today, I spend 80 percent of my time at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, and the remaining 20 percent leading the group focusing on science communication at the Freudenthal Institute.”

Van Sebille's main focus on the field of science communication is explaining why science is made and why it matters. Not everyone trusts studies on the climate and some see universities as some kind of leftist church where scientists are nothing but activists presenting the public with doomsday scenarios and telling everyone not to take planes or eat meat ever again.

“I find it important for scientists to talk about how science works. What’s the process like? If not everyone agrees with the results of a study, we should say that. Be realistic, provide insights. But there are things there is a general consensus on: all my colleagues are convinced that climate change is real and that it has great consequences. Science is not an individual opinion. It is constantly in development, as Naomi Oreskes once wrote in her book Why Trust Science.”

Except, it doesn't always go this way. According to him, the media tends to frame the news in a certain direction, which means that sometimes studies are presented in a different light than intended. He speaks from experience, as a few weeks ago he found himself in the spotlights all of a sudden. Camera crews from the Dutch channels NOS and RTL ran into each other in the hallways of the Buys Ballot building, wanting to interview him and the PhD candidate Mikael Kaandorp, who he supervises. Together, they discovered that there is less plastic floating in the oceans than assumed thus far. Good news, then. The question is how much less. NOS reported that the estimates went from 50 million tonnes to 3.2 million tonnes but German news outlets reported on the same study saying that it showed that there was more plastic in the oceans than previously thought. How come?

“The issue with this study was that it was the first one really looking into how much rubbish there is floating around in the ocean. So, you can't really compare it to anything. On the Dutch press release, we chose to compare our results to previous estimates which had been much higher, thus concluding that there is less rubbish in the oceans than had previously been assumed. Do you see how that is immediately framed in terms of ‘more’ or ‘less’? So, the media wrote that there is less plastic waste than before and that the oceans are doing better now. But that is not true, there simply wasn’t any previous data. The study pointed out that if you really measure accurately, there’s less plastic waste than had previously been assumed by the United Nations and other organisations. It wasn’t based on any scientific study. In Germany, the media used our study to point out that plastic waste is a big problem for the ocean."

This incident is demonstrative of the things scientists need to be aware of when they publish information. “I got phone calls from all over the world, asking what was up. Some environmental organisations didn't appreciate the message that things were not that bad. It became clear to me how much you have to be careful of how news is framed. When it’s about the climate, we have to show just how disastrous the situation is and stress what will happen if we don’t act now. But we also have to indicate what is already being done. A huge amount of CO2 emissions have been prevented since 1997 when the Kyoto Protocol came out. We are working hard on the energy transition, it's not all bad news."

Van Sebille does not believe that we are headed towards our own destruction as some transitions are going faster than expected, while other developments are going slower than hoped. “A lot has already happened. Look at the increase in solar and wind energy. But we’ve got to be aware that we cannot keep going this way. The climate has changed throughout all ages but the environment was able to gradually adapt. Now, because of the intensive way we humans are using the earth, these changes have been happening at breakneck speed, which is why we can’t manage to adapt to the environment. If the water levels were to rise in the Netherlands, should we all just move to Germany? What about mounting temperatures in Africa? Part of the world will become uninhabitable, so it makes sense for that group to come to Europe. It is important for us scientists to keep pressing forward on this. Still, I trust that it’s not too late yet and that we can achieve a lot.”

The measures necessary to contain climate change will hurt. In addition, a far-off future is hard to imagine for some people, which is why politicians' attention tends to quickly shift away from the climate. But Van Sebille underscores that other key issues of our time, such as poverty and migration, cannot be considered separately from the climate. “Over the past ten years, I've come to gain more and more insight into the fact that it's all connected. You cannot isolate climate policy from your approach to fighting poverty or preventing migration. We should be looking at interconnections instead, hence my call for interdisciplinary research. As a climate physicist, I can indicate what kind of problems we will encounter but I don’t have any ready-made solutions up my sleeve. Economics can provide suggestions for a new approach to welfare which will both try to solve poverty and be climate-friendly. But it is also important to get social scientists, Humanities scholars, and medical experts involved. How can we motivate people to change? There is a group in Delft called Technopositives, which bets on bright minds to come up with some kind of technological solution. Fair enough, that's alright, but it has to involve the entire system.”

Young people are the ones who worry the most about the future. This spring, students occupied UU's Minnaert building, demanding the university take the climate crisis more seriously. In their view, UU should be talking about the climate in terms of a state of emergency. They would also like to see the university break all ties with the fossil fuel industry.

“I understand these students. They’re concerned. As a scientist, I won’t sit and protest on the motorway but I’m concerned too. I’ve got a banner in my office that says ‘Prof strike for climate’. But in order to have authority in society, we have to keep our eyes on the prize, maintaining our credibility by presenting evidence-based research and putting pressure in that way.”

Although the protest group End Fossil: Occupy, to which the students who occupied UU's building were linked, calls for the university to sever of all ties with the fossil fuel industry, some scientists believe that collaborating with such companies is necessary to make the transition a reality. UU has recently issued a document pledging to only work together with companies or organisations from the fossil fuel industry if they demonstrably contribute to the transition. Van Sebille does not think that's enough. “I attended the discussions organised by UU last spring and I understand that some scientists prefer to work with the fossil fuel industry as a means to speed up the transition. But I still don’t believe in that. The fossil fuel industry has demonstrated time and again that they're having a hard time letting go of their fossil fuel mentality: they're not permeated by the idea that the energy supply needs to change drastically. I think they will mainly use scientific research for greenwashing purposes, which is why I’m in favour of radically cutting ties with this industry. Let's collaborate with other companies, companies that do have clean energy as one of their goals. It’s perfectly possible to find people still working with fossil fuels but consciously opting for a new direction. Or let scientists work independently and then offer the results to other so that they can realise the transition in practice.

Van Sebille is happy to be able to call himself the first Professor in Public Engagement at UU. In his view, the university is on the right track. He applauds the fact that the university uses the Sustainable Development Goals as its principles, even though he also thinks that those goals are rather broad and can sometimes be contradictory. “If you want cleaner oceans, then you should work on protecting the sea and the fish but that can have dire consequences for the food supply in certain villages. Both are SDG goals.”

He hopes not to be the last professor in this role. “I believe that every faculty should appoint someone like this. Then we could work together.” As part of his inaugural speech, Van Sebille said that he actually dislikes the term Public Engagement as it "is only understood in academia. It’s meaningless outside of it. I propose to broaden it by saying 'science with and for society.' That includes science communication. How do you position yourself in public debate as a scientist? But it also includes citizen science, in which you ask society for help with your research, such as when researchers involve people in collecting data. There’s also co-creation, a form of science where academics work directly with partners from outside the university."

“As a scientist, you have to engage in a dialogue with society. What’s on people’s minds and what can science do with it? At Betweter festival, we presented a so-called Climate Vote, in which we tried to measure how people felt about the climate. Afterwards, I discussed the results with several participants until late. We can also try to find answers to the questions that bother people. For instance, the Utrecht Young Academy came up with a Climate Help Desk, to which people can send questions about the climate, and then volunteers will find the answers and publish them on the same website.

“Lastly, I think we're also doing Public Engagement when we involve young people in our research. Next week, I will have the privilege of formally reopening the University Museum, which plays a significant part in that regard. It’s important for scientists to visit schools and talk about the research they’re working on, why it matters.”

Van Sebille would also like to get society more involved when coming up with research topics. Last year, UU celebrated its 385th anniversary by doing exactly that: the project was called Utrecht Science Agenda. “I was involved in that, too. We received a lot of nice questions but it turned out to be quite difficult to really find a place within the university for research based on those questions. Some people simply asked for facts and you can’t research that. But there were good questions too, such as which place in Utrecht is the healthiest to go for a run? That could encompass research into air pollution, for instance. But, at the end of the day, it has to fit into someone’s research work in order for something to be done with that question."

“You also have to be careful not to turn the university into a consultancy agency, which would be unfair competition with specialised agencies. I’d prefer to see the return of science shops. In the 1970s and 80s, people could go to said shops to ask practical questions about societal topics, which were then studied and answered by students or researchers. When I was a student, I once measured the noise pollution caused by trains in Den Bosch, as requested by people living in the vicinity of the tracks.”