Three-day occupation yields disappointing results

‘We’ll try it peacefully at first’

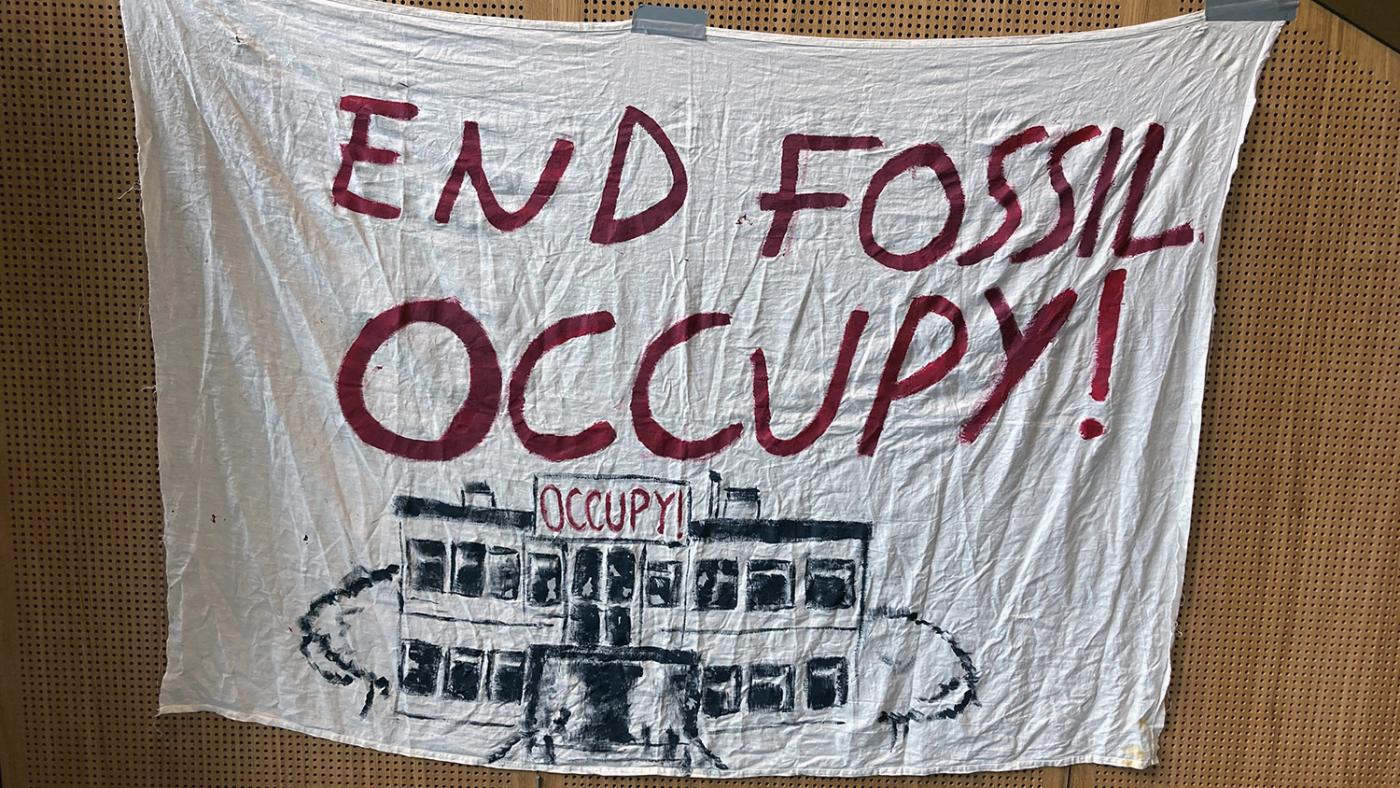

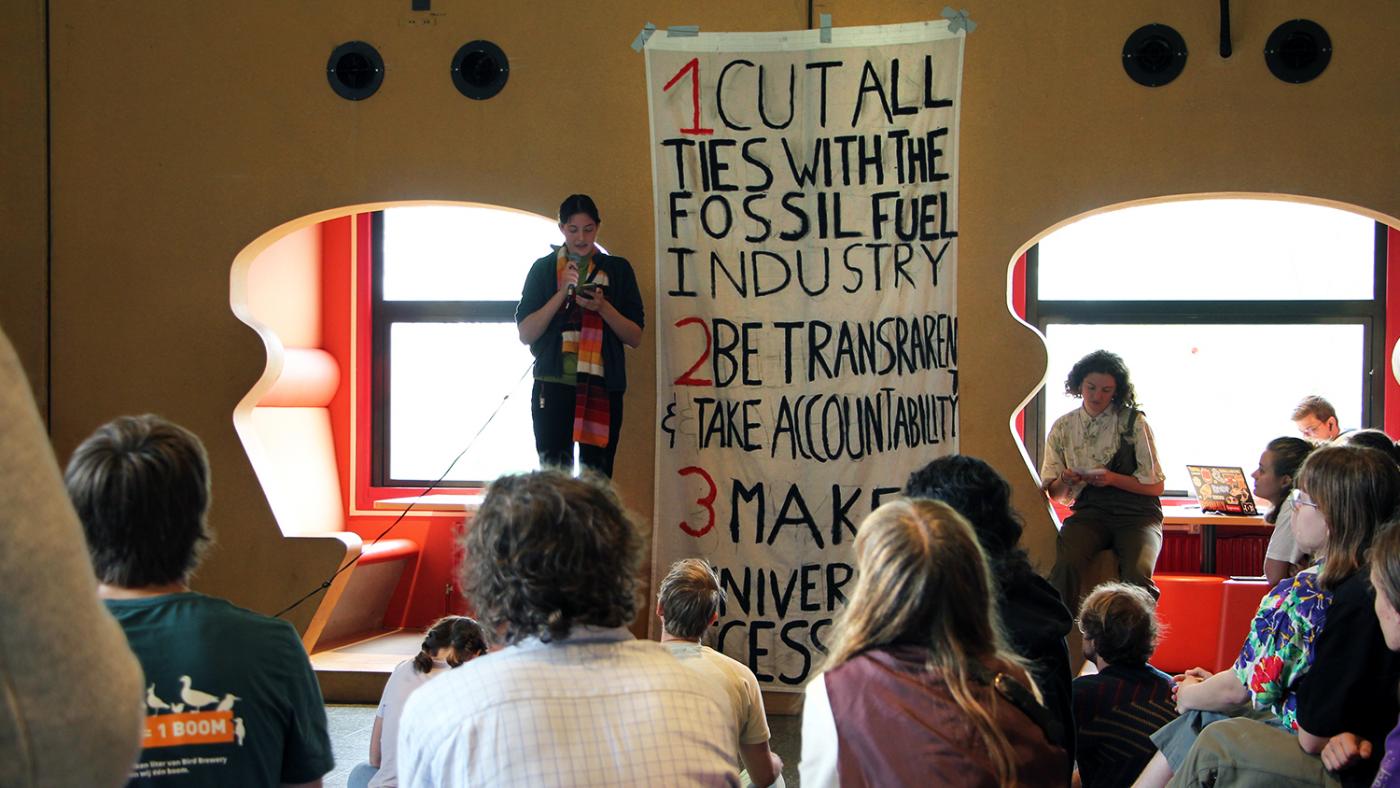

Monday morning, 8:30 am. Around forty protesters from End Fossil: Occupy gather at the Utrecht Science Park, planning to occupy a building. They want the university to break its ties with the fossil fuel industry as they believe that companies like Shell are the biggest hurdles on the road towards a transition to sustainable energy. Other than that, they have 34 additional requests, related to three main demands. Some of these requests are less about climate and more about equality, such as giving international students the same rights as Dutch students — giving them free public transport cards, for example. Around one-third of the protesters are international students. Their demonstration is part of a worldwide month of action called #MayWeOccupy, in which more attention to climate change is going to be demanded at several universities across Europe.

The protesters split themselves into three groups (which they called "signal groups") that gathered in three different places. The gatherings started with an introduction round in which everyone shared their pronouns (he/him, she/her, or they/them). The goal was to create an inclusive space in which everyone was equal. This habit suits the protesters’ desire to change the entire system: they identify capitalism, inequality and patriarchy as important causes of the climate crisis.

Some students are rather tense as this is their first protest ever, while others have already participated in the much more radical protests organised by Extinction Rebellion. For privacy reasons, many of them use fake names when talking to the press. Some refuse to be photographed.

Also for their own safety, the protesters have to sign the so-called arrest form, in which they share their own contact details and those of a person who can be called in case they get arrested. “Day and night, there are people following the protest from a distance, who can help us in case we get arrested,” explains Rob, a student of Computing Science and a member of the subgroup Green Finger. “We’re also in touch with an attorney who is always available for us.”

At this point, they still don't know which building they will occupy. Only three people are in the know: the managers of the three signal groups. Everyone's brought sleeping bags, pillows and clothing to survive at the university for three days.

Minnaert or Utrecht University building?

When the protest was announced on End Fossil: Occupy's Instagram account a week prior, there was a rumour that the protesters would occupy the Utrecht University building near the Dom Tower. But the movement figured that they would be thrown out of there quickly as they would be disrupting inauguration speeches, PhD ceremonies and other formalities. The Minnaert building was a much better option, says Rob. “It’s reasonably central, many students pass by, and we won't be blocking any classes. We really want to be able to run our programme for three days and this building gives us the biggest chance at success.”

The organisation was well prepared, which meant that the workshops, lectures, jam sessions, and even parties that went on until midnight all went smoothly. Nothing was broken and all protesters adhered to the rules – which, by the way, basically created themselves. Drugs, alcohol, and violence were strictly forbidden. The university imposed some additional rules too, such as not allowing anyone to enter the building at night and not breaking anything. The protesters were allowed to sleep in the canteen of the Minnaert building because it is warmer than the great hall.

Bart, a student of Media Technology, who attended the rave on Monday night, wishes the protest was more radical. “The university is not being affected by the occupation of this building. No one is bothered, so we won’t achieve much. Look at the strikes at the Albert Heijn distribution centres: supermarket shelves were empty as a result of that and Albert Heijn just can’t let that happen. I think End Fossil: Occupy would have had more impact if they occupied the Administration Building or another place where they would really be in the university’s way. But this is better than nothing, of course.”

Anouk, a student of Liberal Arts & Sciences who joined the protesters on day two, was happy that things were relatively peaceful and small-scale. “It makes it easier to join for the students passing by than it would have been if it was an aggressive and hostile action. Besides, this way they are not expelled from the building and the Executive Board can take the time to have a conversation with us. Of course, there are other organisations such as Extinction Rebellion that are more radical in their way of protesting. But I think that should be step two. We’ll try things peacefully at first and, if the university doesn’t take us seriously, we’ll have got a good reason to follow up with something harsher.”

Many students sympathised with the protest. On Monday morning, the university sent an e-mail to students and employees, informing them of the occupation. Sophie, who often visits the building to study, heard about the protest that way. “When I read that the Minnaert building was being occupied, I had a rather different image in my mind than what I ended up seeing here. It’s a lot smaller than I expected. I’m glad that they’re not disrupting any classes but, on the other hand, I’m not sure they will get much by protesting this peacefully.” Although she agrees with the protesters’ demands, she didn’t join them. “They’re already protesting so I don’t have to,” she says with a laugh.

Disappointed

However, the protest almost escalated on Tuesday after a meeting with the Executive Board. The protesters concluded that the board’s assurances were far too meagre and issued an ultimatum: before 5:00 pm, the university should officially declare a state of emergency about the climate crisis, and promise not to welcome anyone with ties to the fossil fuel industry to participate in career days or give a guest lecture at the university. The deadline passed without a reply from the university, so the protesters headed to the Administration Building, where the Executive Board was still meeting to discuss the demands. The students were denied entry by security and were threatened that the Minnaert building would be evacuated too if they didn’t listen.

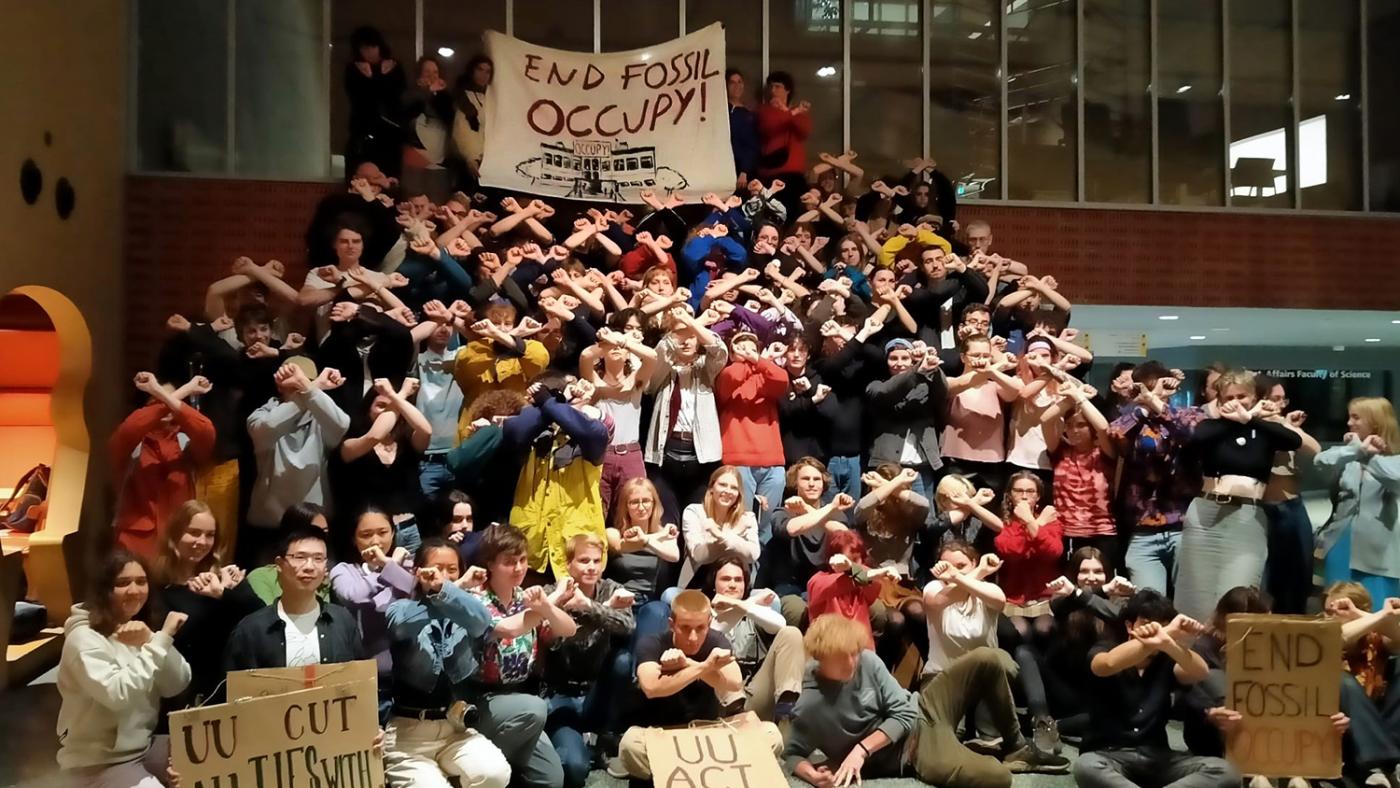

As the three days of protest went on, the protesters’ feelings slowly turned from tense hope to a certain disappointment. Although the classes and workshops were popular and the protest comprised eighty people at its peak, it didn’t seem as though the university was willing to comply with their demands.

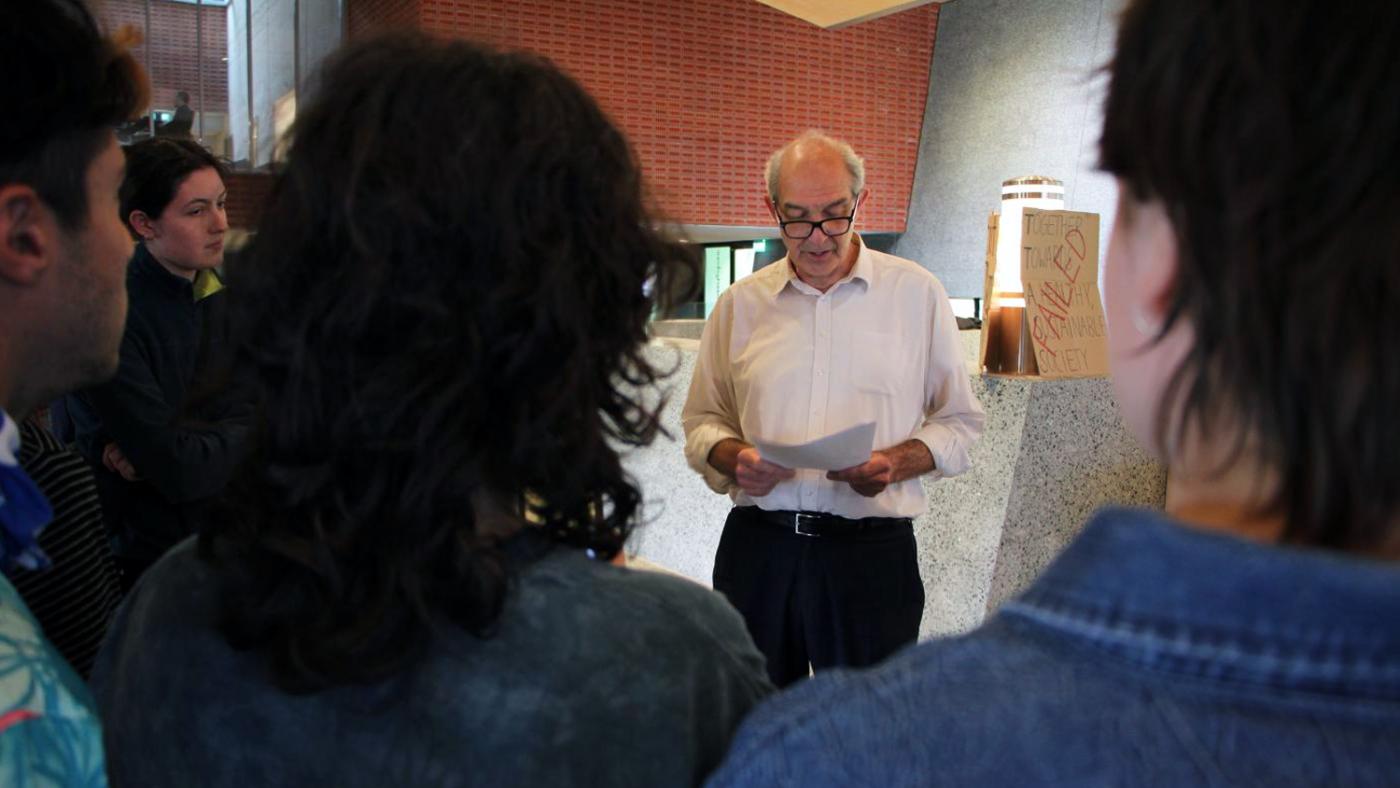

On Wednesday afternoon, the president of the Executive Board, Anton Pijpers, showed up, shortly before the protest was about to end. He came bearing good news. “From now on, the university will use the term ‘climate emergency’ in its official communication,” he told the protesters. “That’s because you made us reflect on it. Until now, we didn’t want to talk about a state of emergency because the university itself isn’t in a state of emergency. However, we acknowledge that other countries are in a state of emergency because of climate change. They're facing draughts, for example.” The occupiers then asked why the university would not comply with the other demand made on Tuesday afternoon. Pijpers replied that the board was still discussing that one.

Discontent

The protesters were not pleased. “The ultimatum was about our two least harsh demands,” stated Bobbie, the protesters’ spokesperson. “They must do a lot more than that.” So, on Wednesday, 3:30 pm, after they had packed all their things from the Minnaert building, the group walked through the rain towards the Administration building, carrying megaphones and banners for one final protest. Security was prepared and blocked the door. The students stood in front of the door shouting their slogans and, afterwards, everyone went home.

Heleen, a Master’s student in Climate Physics, isn’t sure what to think about such a peaceful protest. “On the one hand, you can reach a broader audience with more radical protests. On the other hand, you get more hate as well. It’s hard to know which approach is more effective in the long run. A friend of mine researched this for her thesis and she concluded that radical activism is more effective.”

The protesters are left with mixed feelings, too. “We’re pretty tired after three days. It was a full programme and we didn’t get much sleep,” says Bobbie. “Although we’re really proud of what we’ve done here, the university only complied with our easiest demand, which doesn’t even require them to change anything about their policy. That’s why we gave UU a new ultimatum: we want to see an action plan before the end of May. So far, things have been going far too slowly. If each of our protests only leads to one single demand being complied with, we might have to switch to harsher demonstrations. Non-violent, of course. But there are plenty of other options.”