‘My greatest ambition is to realise more new rooms more quickly’

He’s settled in, Rob Donninger – successor to director Ton Jochems – says in the majestic building at the Plompetorengracht that houses the SSH offices. “After six months, my trial period is definitely over.” He’s clearly thinking about the future, with plans to expand the SSH housing stock. “The ambition to do so was a little lower for a while, because demographic estimates indicated the number of youths – and with it, the number of students – would decrease. But there are new developments now. There might be fewer young people, but a larger share of them goes to college. And we’ve had a lot more students from abroad coming to the Netherlands in the past few years.”

More living space for students in Utrecht

There are two ways to, as the director says, ‘expand the availability of the offer’. The first one is constructing new buildings, the second is to manage more buildings that belong to other parties. “They might belong to the municipality, for instance, or another housing corporation, or an individual who owns a building.” One example of this is the housing property De Sterren in Rijnsweerd, which is owned by an individual investor. Donninger says there are parties who want to do something for the city and its students, but don’t have the knowledge or energy to manage those properties and rent them to students. “They’ll build or renovate a building, and then ask us to let the rooms, and maintain them.”

Photo DUB

Photo DUB

The SSH would prefer to construct more buildings. “But finding a space for an affordable price is, to say the least, incredibly difficult. Constructing new buildings depends on finding a good location.” What that entails, is hard to define, Donninger says. “Whether a location is interesting to us depends on multiple factors. Students prefer to live in the city centre or close to it, or near the educational institution. “We’d love to construct a fifth building in the Utrecht Science Park. As more and more people come to live there, it’s establishing its own dynamic, and thus becoming a more interesting place to live. We’re currently in talks with the university and municipality.”

The university does see some possibilities, director Fiona van ‘t Hullenaar had said in a previous interview with DUB. If Veterinary Medicine’s Androclus Building is demolished, or the Central Laboratory Animal Research Facility, one of those locations could be used for new housing units for students.

Donninger also doesn’t rule out locations near the Merwede canal, the Beursplein, or in Overvecht. These are areas that would mean a little longer cycling trip to the Science Park, but could still be interesting if the housing is high quality, he thinks. “Rooms with their own bathroom and a shared living area and kitchen, for instance.” The scale is also a criterion. “In a new, yet to be built neighbourhood like the Merwede canal, you can build a few hundred student housing units between the couple thousand homes.” That way, you’ll immediately create a community, making it more attractive to students than when you have just thirty students living amongst thousands of non-students.

Housing allowance for students

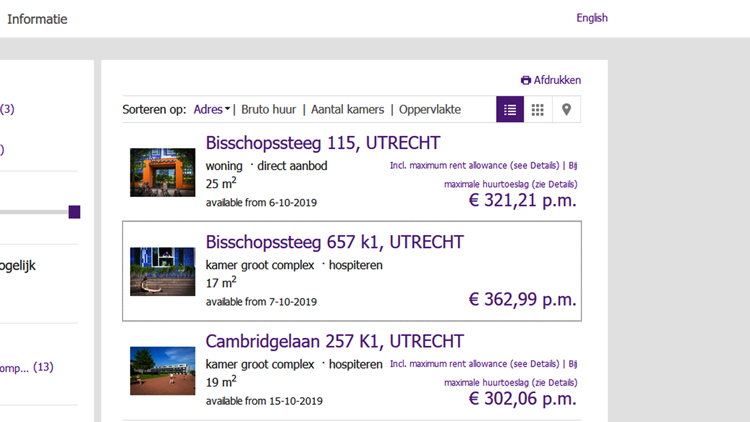

Screenshot website SSH, September 16th, 2019

Another issue with finding suitable construction locations is not just that they’re few and far between, but that the growth of the economy means the competition from other parties is great. That’s quite obvious in Utrecht from the large number of studios that were built in the past few years. “The current regulations make it more attractive to construct independent living units instead of classic rooms. Tenants of a studio can get a housing allowance, tenants of a room can’t. That makes studios interesting for investors, and relatively cheap for students.”

Those who rent a studio of up to 720.42 euros a month are eligible for a housing allowance; people under 23 years of age can receive a housing allowance for a rent of up to 424.44 euros. The rent of a studio in comparison to a room are getting smaller. An example: a student renting an SSH studio who receives housing allowance pays 325 euros a month; for a room, that’s 294 euros. “That’s why we think it’s a foolish regulation, and we think the law should be changed.” People living in shared housing should also be eligible for housing allowance, he says, because it turns out students enjoy living in a shared home.

Rooms with their own bathrooms

For that reason, the SSH would like to add more student rooms to its stock, Donninger says. “Living in the IBB or Tuindorp-West is still popular. Living in a student housing property with shared facilities also helps combat loneliness amongst students. Because loneliness is still quite prevalent.”

He does think these shared housing units will change in appearance. “Students living in rooms would prefer to have their own shower and toilet. I think we’ll be moving towards that: building smaller units with five to six rooms, all with their own bathroom facilities, and a shared living room and kitchen where the residents can meet each other.”

Interviews, waiting lists, and urgency

The new type of student housing could also bring change to the interviewing process for new residents. There’s barely any student in Utrecht who can avoid the interview process. Donninger doesn’t want to change that, although he does acknowledge that the interview process has its downsides. In defence of the system – in which ten students who need a room and have been registered with the SSH the longest, visit the home they want to live in, and are then assessed by its current residents for the label ‘suitable housemate’ – Donninger says most people who need a room “are chosen after 1, 2, 3, or 4 times. It’s difficult to think of a good alternative for communities who live so close together.”

Photo DUB

The SSH does have a safety net for students who don’t get picked in interview sessions. They can be placed somewhere by the SSH. “Those rejections are something, though. Of course they’re detrimental to your self-image. When I was a student in Amsterdam, I didn’t have to interview. I was placed in a dorm hall and I ended up in a very nice dorm. But there were also dorm halls that were less fun.” Although the data for home-seeking students paint a positive picture, that doesn’t say anything about the number of students who might never go in for an interview and who, after two years of being registered with the SSH, apply for a studio, or wait for new buildings. “We don’t have any data about that.”

Donninger says it’s uncertain at this time whether the SSH will create units that won’t require interviews. “If we are to build smaller units in which you only share the kitchen and living room, then perhaps you can keep those liveable without interviews. Especially if you know from the start that there’s not to be any interview process for new housemates. It’s something to think about.”

Donninger won’t change anything about the urgency regulations. The most important criterion now is the time someone’s been registered with the SSH, and he says that’s the most social criterion. “Why would a student from Groningen have a greater, more urgent need for a room than one from Utrecht or Beijing? Who decides that? Distance alone is not a criterion to me. Imagine the student from Utrecht is actually living in a socially unsafe environment, and it would be a great thing if he could move out and live on his own, while a student from Deventer lives in a very safe home?”

Students from abroad

For international students, finding a room in Utrecht is quite a different story. Although they can also register with the SSH XL when they’re 16 years old, that’s not the most logical step for them. “At that age you probably have no idea you’ll want to study in the Netherlands one day.”

The other problem with international students is that they all need a room in Utrecht in the same period, Donninger says. “They show up in bulk, and all of them need a room as quickly as possible because there’s no option of living at home for a little while longer. Their limited network makes it harder for them to find a room via another route as well. That’s why the university reserves a few hundred rooms where internationals can live for a year; after that year, they have to use the regular housing system.”

Because it’s harder for internationals to get a room, the SSH conducted an experiment last year, based on an idea from residents organisation Boks. The experiment entailed that the SSH added internationals – who technically didn’t have a long enough registration period – to the list of interview candidates for certain rooms. “Boks said that this way, internationals would get a real chance, and that turned out to be correct.” The experiment has since ended. Although the results were positive for internationals, the SSH doesn’t see it as a true solution for the ‘concentrated influx’. The housing organisation will meet with Boks and the educational institutions to think of structural alternatives. “But again: more available housing is the best solution. That way, it’s not a problem to reserve part of the offer for international students.”

Photo DUB

The digital landlord

Those who rent a room from the SSH never, or hardly ever, meet an employee of the organisation. The application process is digital, keys are usually handed over from previous resident to new resident, and rent is collected automatically. It’s only whenever something in the house has to be fixed that a handyman shows up, and larger properties have a manager who keeps an eye on this. Efficient, or impersonal? Efficient, Donninger says. “To keep the rents as low as possible, we keep our organisation small, and we try to make as many processes automatic as possible. The more we can automate, the more hours are freed up for human contact where it’s necessary.”

Students, he claims, don’t mind at all to communicate exclusively through email, WhatsApp, or chat robots. “Even if communication is digital, that doesn’t mean it’s impersonal. Look at a website like booking.com. They contact their visitors in a very personal way. My son, also a student, doesn’t mind communicating through email, WhatsApp, or chat robot at all. He doesn’t necessarily have to talk to or see a person.” But still, there are moments when residents prefer complaining to a person than to a computer system, he knows. “My daughter, who’s studying in Leiden at the moment, had a broken heating system. When the repair man came, he said he wouldn’t leave until the heating was fixed. That was exactly what she needed at that time – at moments like that, human contact is great.”

Issues with housemates

Photo DUB

Human contact is also necessary when there are issues in student housing units regarding the behaviour of fellow residents, Donninger states. “If we receive word, for instance, from residents who are worried about a fellow resident, someone has to go and take a look. The managers we employ try to keep an eye on things and to check how the residents are doing.”

If someone truly causes trouble, like in Casa Confetti where a resident set fire to his room, and another resident stabbed a housemate’s guest, it can take a while before the room is let to another student. “I’m not going to comment on these specific cases, I’ll keep my answer general. When a resident causes a disturbance, or is growing marijuana in his room for instance, we’ll start by asking the resident to move out. Usually, they don’t even want to return to the home where there are problems. Sometimes, it takes a while to convince them. That leaves their housemates in uncertainty for a while longer. In those cases, we’ll sometimes find an alternative location, depending on the situation, because we definitely won’t for people growing marijuana in their homes. But to end with a positive message: these are truly the exceptions. If you see how many people live so close to each other and with each other in student housing units, there’s relatively little that goes wrong.”

Who is Rob Donninger?

Rob Donninger started his studies in Politics and Public Administration at the University of Amsterdam in 1980. After his university exams, he moved on to study Planning, Housing, and City Renovation. After working for a research and advisory body in the field of living environment, he started working for housing corporations. Before coming to Utrecht, he worked in Alphen aan den Rijn, where he left after completing an assignment to merge two housing corporations, ‘because everything was going as it should’. After 12 years, he was looking for a new challenge. “One day, my wife said there was an ad for a job in the newspaper: director of the SSH. The description satisfied everything I was looking for. I wanted more city dynamics, a metropole, and a different dynamic than in a regular housing corporation, a different market, a different group of people. I found that here. And no, I didn’t become director to help my own children find a room. They’re doing things by the book, by the rules that apply to everyone.”