The story of Frits van Oostrom

‘Professors always stay with you, so they should inspire’

His space in the characteristic building on Achter de Dom will soon be gone. That's where some of the university's professors have their offices, overlooking the Dom Tower and the entrance to the Faculty Club. Just a few more days and Frits van Oostrom will have to clear his room entirely and there will be no successor in his study, as the university wants to dispose of the building.

His farewell, which will happen on Friday, May 12, cannot be called modest. He will give his farewell speech in a packed Dom church, with the Minister of Education himself, Robbert Dijkgraaf, as one of the guests. On the same day, his latest book De Reynaert, Living with a Medieval Masterpiece (available in Dutch only, Ed.) will be published in an edition with 10,000 copies. There will be little time to rest for the soon-to-be emeritus in the next few months, as he will be touring bookstores and participating in radio shows such as Frits Spits' Taalstaat and Vroege Vogels. DUB meets him to look back on his career.

'The importance of the passionate teacher'

The first part of his new book is about teachers and there is good reason for this. Frits van Oostrom considers inspired teachers the core of education. In 1971, he chose to study Dutch in Utrecht, not Leiden, where he lived at the time. The fact that his father had studied in Utrecht and that he himself was born there certainly influenced that decision. "But my Dutch teacher at the Leiden grammar school was enthusiastic about studying in Utrecht. This teacher, De Zoeten, used to tell great stories about Dutch literature."

With sixty classmates, Van Oostrom ended up at Emmalaan, where the programme was housed. He calls it a bell jar, a small community where you took turns in small rooms to be taught by the professors. It was the 1970s, the time when the 1960s were breaking through in the Netherlands. "As students of that time, we wanted more Sociology of Literature. But then professor Sötemann said: 'Interesting, in this case, you should study Sociology.'" Guus Sötemann taught Modern Literature and Analysed Poetry. "I remember exactly when we went through the poem Het geheim by P.C. Boutens. We didn't understand a thing but, after class, Sötemann gave us the feeling that we had got to the bottom of the poem ourselves. That was great."

In those days, professors and students were closely in touch. "We had a game night at Cunera on Nieuwegracht. I was in the group with the medievalist Wim Gerritsen, who would later be my teacher. The game was a brainteaser that demanded us to devise a solution together. We managed to solve the puzzle but then the game leader said that any solution was good if you figured it out together. Professor Gerritsen furiously stood up: 'It shouldn't be so difficult to come up with a game with only one solution.' That was typical in many ways. His full commitment to finding the right solution."

These are the examples Van Oostrom had in mind when he became a teacher himself. In Utrecht, he no longer lectured on the Middle Ages, but served as a programme leader in the Descartes Honours programme. "A really great programme, where students from different faculties come together for two years. It's about practising science, the social context, humanity and robotics. I always had a personal conversation with the students about their achievements and ambitions in the future. I really appreciated the interaction, even if it was not about my field."

Sadly, he's been noticing that Dutch secondary education places an increasing emphasis on "the method", the textbook and the teacher has the amanuensis role. "If you ask students to look back on their secondary school or studies, they will never say 'wow, what a great method I had'. No, it is the passionate teacher they remember."

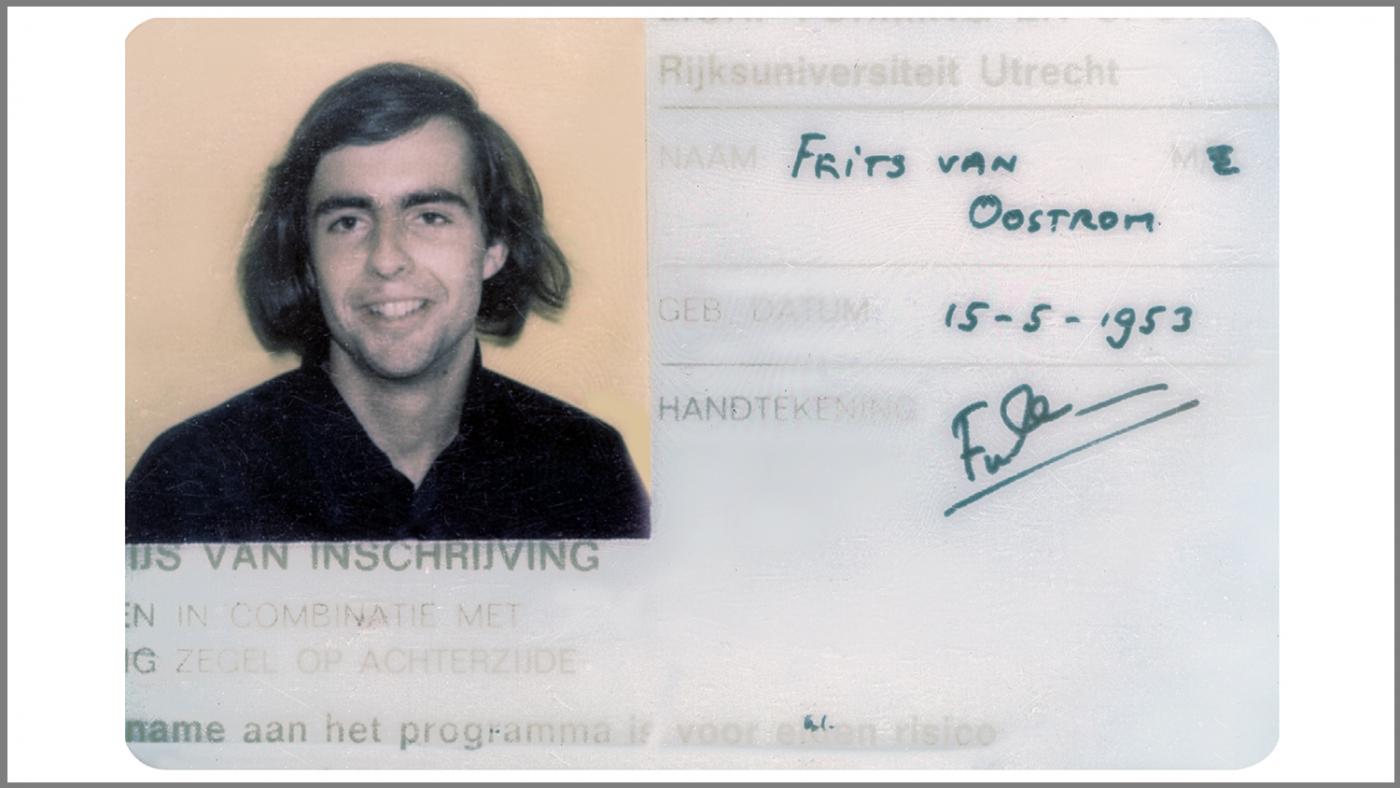

The youngest professor in the Netherlands

After his PhD in 1981, Van Oostrom wasn't sure what to do. His contract to do a PhD expired and the job market was pretty bad. Then a vacancy for Professor in Romanticism Literature in Leiden was opened. Back in those days, a professor was appointed by the Dutch king or the minister of education. Similar faculties advised on candidates. Van Oostrom's name was among the suggestions. Indeed, there was a nomination before the board in which he was ranked first. He hesitated, it was a big step and he was only 28 years old. At the same time, it was a huge opportunity.

The board of Leiden University hesitated too. The Dean of Arts warned that the minister would probably not accept to appoint such a young scientist as a professor right away. Leiden suggested that he should first come and work as a staff member for a few years and move up later. "If this had been the decision, I probably would have accepted it. But the reason they gave was that the minister was not expected to approve it. At the time, I knew Jan Terlouw fairly well. He was the minister of economic affairs. I asked him whether age was a reason to block such an appointment and he replied: 'Usually, I never interfere in the affairs of another ministry but I find this rather strange. I will talk about it with the Minister of Education and Science'. A few days later, I received a handwritten note from Minister Kemenade saying that age was not an issue at all. With that note in hand, I called the Leiden Board of Governors. They were very surprised but couldn't get out of it. That's how I became the youngest professor in the Netherlands."

Looking back, Van Oostrom agrees that he was pretty young. "You have to lead, after all. And you want to prove yourself. In retrospect, I certainly fell short in terms of humanity in those first few years due to lack of life experience."

In September, he celebrated forty years as a professor, a milestone rarely achieved in academia. What is his opinion about the recent debate concerning the status of professors in the Netherlands? "There is something crazy in our system. What is a professor? Someone who, besides teaching, also conducts research. How do you explain that abroad? Why shouldn't more people be able to supervise a PhD student? However, it is good to have certain ranks. A professor should lead a research group. But you can make the grade structure less rigid."

The decline of Dutch as a subject

When Van Oostrom became a professor in 1981, around two hundred students chose to study Dutch in Utrecht every year. Now that number is around forty. There is a shortage of Dutch teachers at Dutch schools and a huge debate about how to get young people to read more. Dutch is not a popular subject among schoolchildren.

"Actually, that is really weird," says van Oostrom. "We think in our language, we look for forms of expression in our language and I sincerely believe that people also love our language. Look at the popularity of comedians, the way rappers play with language and the rise of young writers. On the TV show De Wereld Draait Door, writers are often invited, which is appreciated. And if you go to a bookshop, there is a huge number of fiction and non-fiction books in Dutch on every possible subject."

According to van Oostrom, the problem lies in education. "Ask students about the subject of Dutch and they will say, 'It is so boring!' There is too little connection between society and the school subject. Teachers do not succeed enough in conveying a love for literature. I remember that, when my own children were at school, the writer Gerard Reve died. The newspaper De Volkskrant devoted seven pages to him. And what did they do at school? Nothing."

Most teachers studied Dutch. So there is also a task for Dutch studies to break the vicious circle. To him, the university has a role to play in addressing the subject in secondary education and should work on making teaching more appealing. Van Oostrom himself was involved in a committee to establish a canon of Dutch history and culture. But he sees such a canon more as an inspiring foundation than as a standard cast in concrete. Time and again, he comes back to the importance of the teacher telling a story.

The story of the Netherlands, example of popularisation research

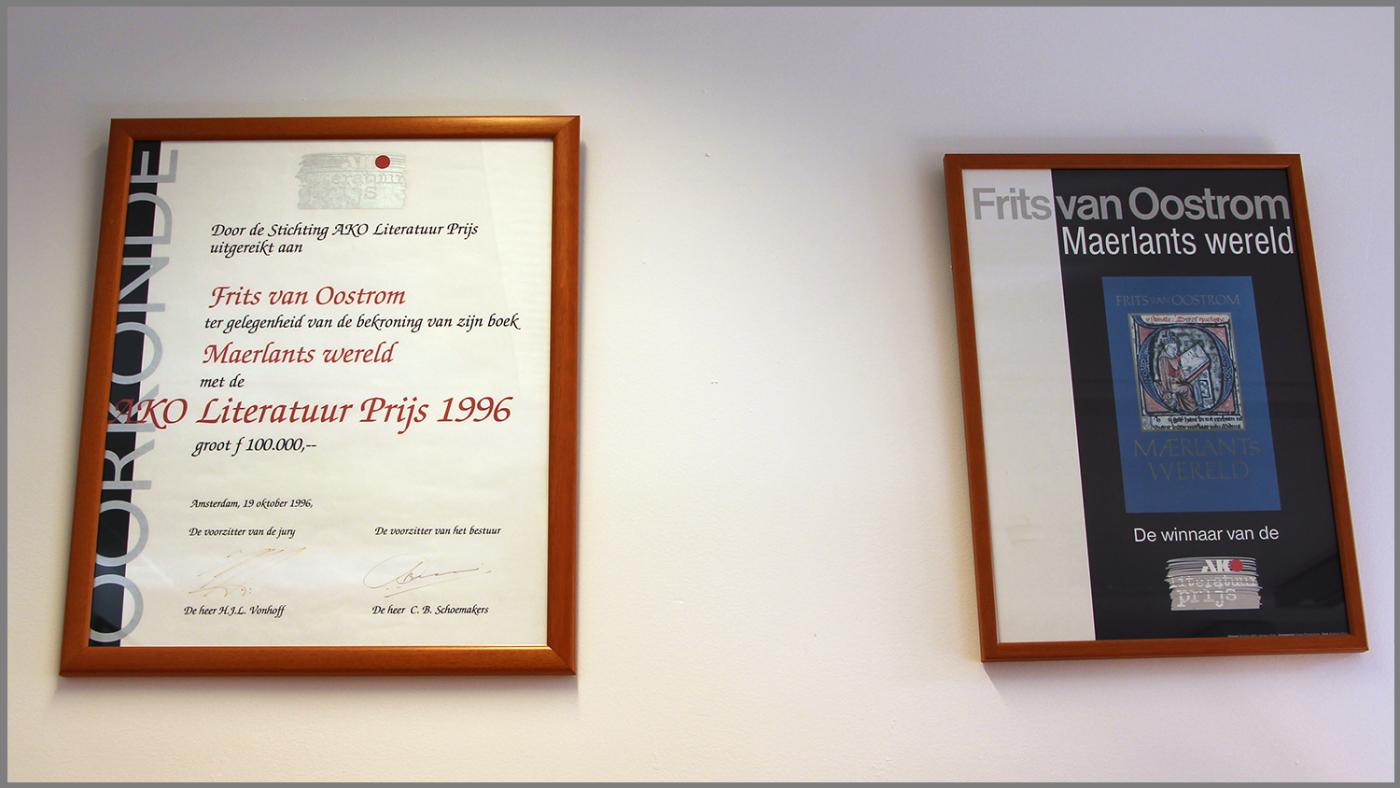

Van Oostrom's strength is that he is a born storyteller. He managed to win a literary prize with an academic book twice. He received the AKO Literature Prize in 1996 for his book Maerlants wereld and for his book Nobel streven. Het onwaarschijnlijke maar waargebeurde verhaal van ridder Jan van Brederode in 2018 the Libris Literature Prize. They became bestsellers.

At the same time, he manifested himself as a researcher. In 1995, he was among the first batch of scholars to receive the prestigious Spinoza Prize. "In my books, I try to find a mix of information that is interesting for a wide audience, but at the same time offers colleagues something new that they are surprised by."

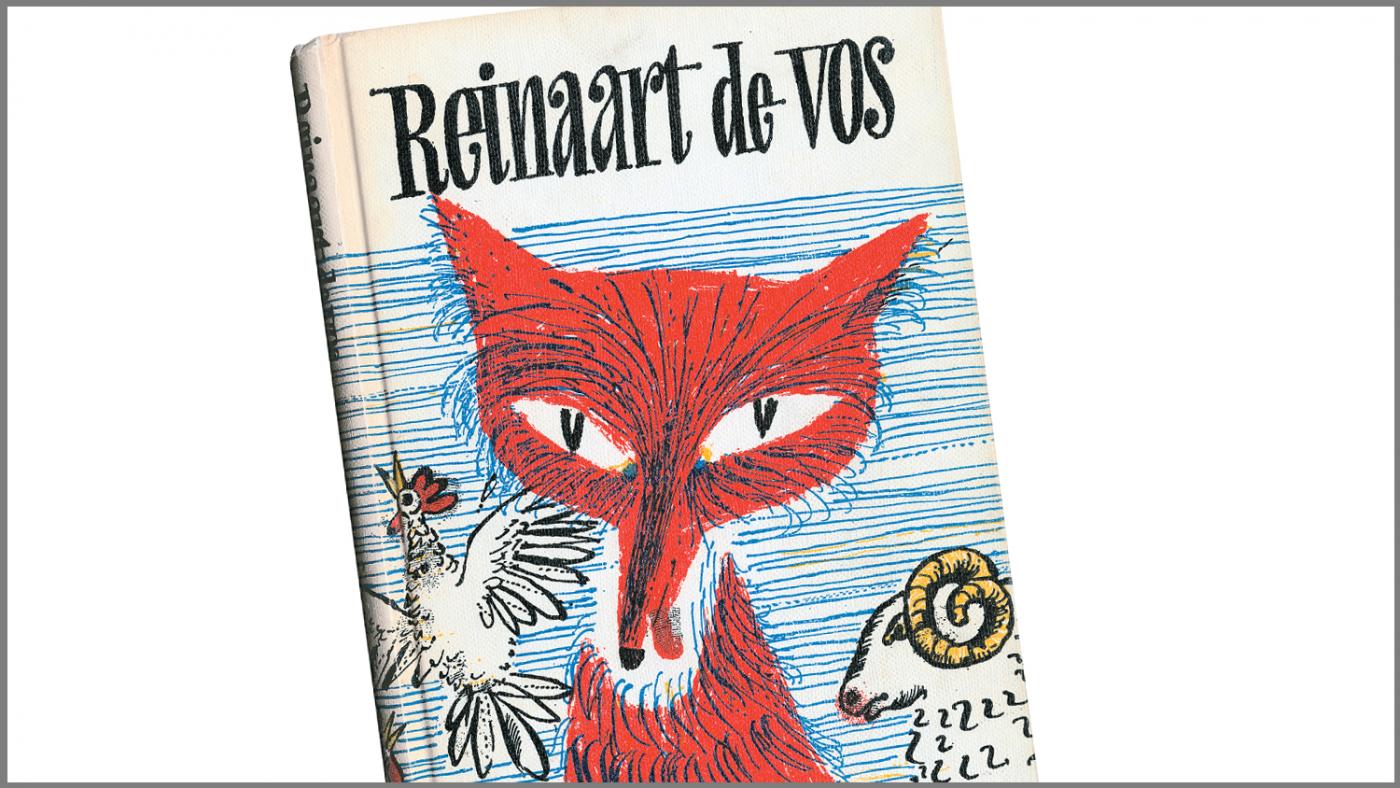

He hopes this is also the case with his new book De Reynaert, Leven met een Middeleeuws Meesterwerk. "De Reynaert is about the story of the fox Reynaert and is a classic in our Dutch literary history. Much is still unclear about the interpretation of the text and its genesis. Who was the author? To what extent are the animals in the story a model for a satire on Flemish society at the time? I looked at the research of past centuries with sometimes obsessive scholars and weighed and thought through many possibilities and wrote that down. This gives us a picture of how this manuscript has been interpreted over the centuries and I also try to draw some conclusions."

This is how Van Oostrom manages to make interest in history accessible to a broad audience. No wonder he was also involved in the recent series Het verhaal van Nederland broadcast by NPO.

He says that initially, there were doubts whether so much money should be invested in such a series and some historians were sceptical about this way of describing history. "In Denmark, this had been done with the actor Lars Mikkelsen as narrator. It turned out to be a great success. You bring the past very close by really re-enacting it. I did make two observations. Don't perform the actors speaking, that would make the story unintentionally potent. And also give space to experts to contextualise the story. They did that nicely. Afterwards, the scientists were delighted with the way history was portrayed and the broad interest generated in their field."

New perspectives and inclusivity in research

When you think of the Middle Ages, you might not primarily think of the social discussion on inclusivity. Yet Van Oostrom draws attention to this in his book The Reynaert. He notices, for instance, that it is primarily male scholars who have studied the work. He is curious about the interpretation of female researchers. In addition, he thinks it would be interesting to have researchers from different cultural backgrounds reflect on the fable. How can you interpret the Reynaert with the story of the spider Anansi in mind? In the book, he himself comes up with an interpretation of a chapter that he believes has references to homosexuality.

"Looking back at the past is always done from a certain perspective," he explains. "Utrecht University lecturer Els Kloek has described history from a female perspective, about women in history we were told very little before that. The same goes for the historical perspective of homosexuality or people of colour. History is generally considered too white and too European. In Leiden, we had Dutch studies, Dutch for international students. Their sense of humour is different and therefore they came up with different text interpretations. From Eastern Europe, again, we can look at texts in a different way. For example, the focus there used to be on spirituality and what we call modern devotion."

Van Oostrom looks for new perspectives and thus new interpretations. What he struggles with is when people want to exclude works. "I experienced a Dutch student saying that we no longer needed to read Vondel because of its relation to slavery from that era. His work would be based on that. That shocked me. You can examine that relationship but not ban a work. Then the violent present undeservedly becomes the measure of things."

A woke approach to the Reynaert, by the way, would interest Van Oostrom. In the past, both right and left ran away with the fox Reynaert. In satire, he puts everyone to shame and makes the king yield big money over justice. "But Reynaert cannot possibly be called a hero with a clear conscience. He cheats, engages in transgressive behaviour, does not shy away from violence and displays psychopathic traits. Thus, much remains to be explored, not only about the text itself but also about interpretations over the years."

Frits van Oostrom, De Reynaert, Leven met een middeleeuws meesterwerk. 2023. Uitgeverij Prometheus. 35 euros.